Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 6, Issue 2 - December, 2013

Factors Influencing 4-H Leader Volunteer Recruitment and Retention

- Boone, D. A, Associate Professor, West Virginia University

Payne, R., Graduate Student, West Virginia University

Boone, H. N., Jr., Professor, West VIrginia University

Woloshuk, J. M., Extension Specialist, 4-H Youth Agriculture/Extension Professor, West Virginia University

ABSTRACT

Volunteerism is fundamental to delivering quality 4-H programs, developing educational capacity, and teaching youth to volunteer. A descriptive research study was conducted to identify factors that influence volunteers to join the 4-H program and factors that affect their decision to leave. The study indicated leaders considered the 4-H program to be effective. Intrinsic motivation of benefiting the community and helping people were considered to be the persuading factors why 4-H leaders join and continue to volunteer. 4-H leaders face problems such as time commitment, children no longer involved, and burnout. 4-H leaders are persuaded to stay through ongoing trainings, continued awareness of resources and curriculum by way of newsletters, phone calls, and e-mails that meet the needs of the 4-H leaders.

Introduction

Volunteerism is fundamental to delivering quality 4-H programs, developing educational capacity, and teaching youth to volunteer (4-H Youth Volunteerism Team, 2004). As a non-profit organization, 4-H volunteers are a vital part of the program. Without volunteer leaders 4-H programs could not deliver quality programs and execute the 4-H mission (Skolglund, 2006).

According to the Independent Sector, in 2010 volunteer time nationally was estimated to be valued at $21.36 an hour. Statewide from 2008-2010, West Virginia had 369,800 volunteers providing 49.7 million hours of service making a 1.1 billion dollar service contribution (Independent Sector, 2010). Nationally, the volunteer rate has declined by .5% for the year ending September 2010 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011).

Nationally, women are more likely to volunteer than men; specifically 35 to 44 year olds. Parents with children under 18 years old are more likely to volunteer, although from 2009 to 2010 the rate for this group dropped from 34.4% to 33.6% (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011). The Bureau of Labor Statistics also reported 42.3% of college graduates volunteer, while only 8.8% of people with less than a high school diploma volunteer. Around the country, 70 percent of the volunteers volunteer for non-profit organizations, such as 4-H. Considering the dollar value of a volunteer’s time, 4-H volunteers in West Virginia provide a vital service and are critical to the success of the West Virginia 4-H Youth Development program. Volunteering is known as one of the most common activities around America (McCurley & Lynch, 2006).

According to the West Virginia 4-H Youth Development faculty publications and job descriptions, the Extension professional with 4-H youth responsibilities in a county is charged with the responsibility to recruit, train, place, screen, evaluate, and recognize adults who serve as mentors and leaders for 4-H members (Townsend, 2004). Davis (2000) found that recognition is a key factor in retaining volunteers.

A number of factors contribute to the reason 4-H leaders quit volunteering. Reasons volunteers decide not to volunteer have been the focus of several studies. In a 2003 study conducted by White and Arnold, they found leaders left because of time constraints and the relationship between the Extension Agent and the 4-H leaders. Skoglund (2003) found volunteers feel alone in their volunteer work and more attention should be given to the ongoing training and professional development of the volunteers These studies support Davis’ statement, “volunteer recruitment and retention is not a one size fits all” (Davis, 2000). The generational differences could be a key factor in the reasoning behind volunteer recruitment and retention differences. Generation X and baby boomer populations have different volunteer motives than those generations before them making recruitment and retention factors different as well (Vettern, Hall, & Schmidt, 2009).

On occasion a local county will experience a significant loss in the number of involved volunteer leaders. The reason for the drop in volunteers is often unknown but vital to the non-profit 4-H organization. One can work to recruit new volunteers by using proven recruitment techniques indicating how 4-H can meet the volunteers’ needs such as skill building, personal relationships, recognition, and making a difference (Eagan, Nestor, Seita, & Townsend, n.d.). In order to eliminate the shortage of 4-H volunteers in the local county, factors that prevent potential candidates from volunteering and factors that cause current volunteers to leave the program must first be determined.

Problem Statement

Extension Agents throughout the country have the responsibility of recruiting 4-H leaders to work with 4-H youth members. The success of recruitment and retention strategies is vital to the delivery and execution of the mission and goals of 4-H. In order to address shortages of 4-H volunteers the factors which prevent potential candidates from volunteering and/or factors that cause current volunteers to leave the program must be determined.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to identify factors that influence volunteers to join the program and factors that affect their decision to leave. The following research questions provide direction for the study:

- What factors motivate individuals to become 4-H volunteer leaders?

- What problems do current 4-H leaders face in the organization?

- What factors cause 4-H leaders to leave the program?

- What factors cause the current 4-H leaders to continue volunteering?

- What are the attitudes of the 4-H leaders toward the 4-H program?

Methodology

A descriptive research, in the form of a mailed survey, was used to collect data to evaluate the research questions. By using a mailed questionnaire, the target population was able to be reached regardless of location. Surveys allow researchers to determine characteristics of groups or to summarize their opinions or attitudes toward certain issues (Ary, Jacobs, & Sorenson, 2010). The mailed questionnaire was to be used to identify potential factors that influence volunteer leaders to join the program and factors that affected their decision to leave.

The accessible population included 128 4-H leaders from a purposively selected West Virginia county who were listed as an active 4-H volunteer leader and those on the inactive members list available at the County Extension Office over the past ten years. There were 114 individuals who met these criteria and had valid mailing addresses. The entire accessible population was used in the study avoiding sampling errors. Frame error was controlled by using up-to-date lists developed and used by the County Extension Service. The lists were examined and duplicates removed to eliminate selection error. Measurement error was eliminated with the use of valid and reliable data collection instruments.

Non-response error was examined by comparing the early and late respondents. It is likely, the non-respondents would reply the same way as the late respondents (Dillman, 2007). An independent t-test and chi-square were used to determine if there was non-response bias. Three different variables were used. The independent t-test was performed on the variable of years as a 4-H volunteer leader. The chi-square procedure was used on the variables hours volunteered and years as a 4-H member. Although no significant differences were found; generalizations were limited to the 43 individuals who responded to the survey.

Instrumentation

In order to identify factors that influence individuals to serve as 4-H volunteer leaders and factors that affected their decision to leave, an instrument was adapted from a research conducted by Post (2007) on “Attitudes of 4-H Club leaders Toward Volunteer Training in West Virginia.” Part one of the instrument consisted of Likert questions, which were divided into three sections including; questions about why the 4-H leader became a 4-H leader, why they believe 4-H leaders continued to volunteer, and why they believe 4-H leaders quit volunteering. Part two of the instrument consisted of multiple response questions asking how they preferred to receive information, what type of support was needed, beneficial trainings, involvement in the 4-H program, as well as demographic questions. Part three consisted of open-ended questions seeking information about strategies used to recruit and retain 4-H volunteers in the county.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability of the instrument was established using the entire data set and the Statistical Package for Social Sciences’ (SPSS). The Likert-type items were tested for reliability using the split-half statistic coefficient. The first eighty-three questions were split into respective sections. For each section of the instrument, the Spearman-Brown coefficient was found to be .60 or higher making the reliability of the instrument exemplary (Robinson, Shaver, & Wrightsman, 1991).

The instrument was presented to a panel of experts to establish its content and face validity. The panel consisted of teacher educators in Agricultural and Extension Education and Extension Specialists at West Virginia University. Each of these individuals has had extensive teaching and/or Extension field experience. The panel of experts concluded that the instrument had content and face validity.

Data Collection Procedures

Principles of Dillman’s (2007) Total Design were used to collect data. An introductory letter and survey was mailed out to all members of the target audience. Each respondent was given a code in order to track non-respondents. The code and key were later destroyed to keep individuals responses confidential. After two weeks a second mailing was sent to all non-respondents. Following the second mailing phone calls were made to the leaders asking them to consider taking part in the study. A follow-up reminder postcard and e-mail were sent out two weeks later, followed by another phone call.

Results

When asked how many hours the respondent volunteered for 4-H during a month, 26 respondents (81.3%) volunteered for 0-5 hours per month for 4-H. Four respondents (12.5%) volunteered 6-10 hours, one (3.1%) averaged 16-20 hours, and one volunteered 21-25 hours a month for 4-H. The number of years they have/were a 4-H volunteer ranged from a minimum of zero years to a maximum of 40 years with an average of 8.12 years (SD = 7.85)

When asked how many years the volunteer had been a 4-H member, 16 respondents (42.1%) were never a 4-H member. While eight respondents (21.1%) were 4-H members for 3-5 years, six (15.8%) were 4-H members for over 10 years, four (10.5%) were 4-H members for 1-2 years, and two (5.3%) were 4-H members for 6-8 years and two respondents (5.3%) were 4-H members for 9-10 years.

Respondents were asked to identify their primary involvement as a 4-H volunteer. Primary involvement as a 4-H leader typically was with community clubs (19.0%) and overnight camping activities (19.0%). Following closely was primary involvement with in-school (16.7%), after-school (16.7%), and special interest/short term/day camps (16.7%). Secondary involvement was noted most often in community clubs (19.0%) and overnight camping (14.3%). County 4-H events leaders were most likely to be involved with included Camp Lakeview 4-H outing (28.6%), 4-H camp (26.2%), 4-H leaders meeting (23.8%), 4-H annual banquet (21.4%), and 4-H movie day (21.4%).

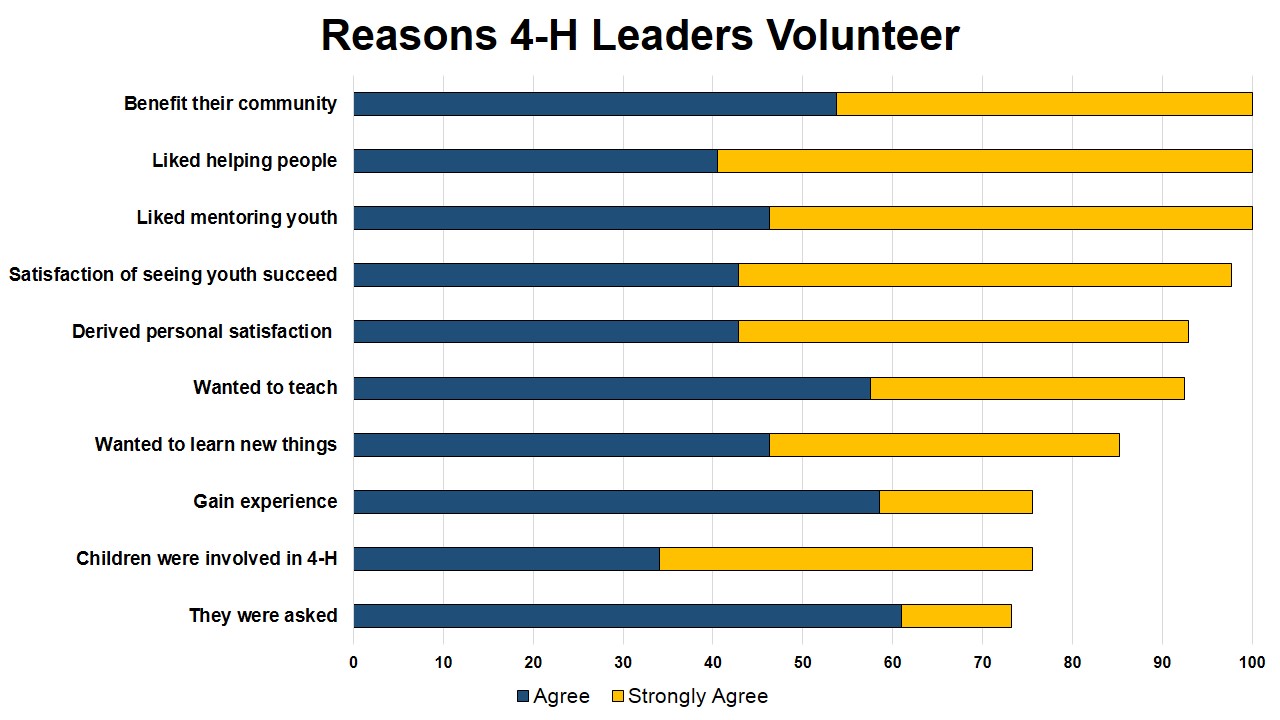

Respondents were asked to identify the reasons they became a 4-H volunteer. The respondents were unanimous on three primary reasons they became a 4-H leader. The reasons were “benefit their community” (100%), “they liked helping people” (100%), and “they liked mentoring youth” (100%). In addition to these three, the top 10 reasons respondents became a 4-H leader included: satisfaction of seeing youth succeed (97.7%), derived a personal satisfaction when working with youth (97.7%), wanted to teach youth (92.5%), wanted to learn new things (85.3%), to gain experience (75.6%), children are/were involved in 4-H (75.6%), and they were asked (73.2%).

The top five reasons that had the least impact on individuals to become a 4-H leader were to gain skills which might lead to employment (25.0%), to receive status in community (26.8%), recognition associated with being a volunteer (43.9%), they were a former 4-H member (46.3%), and they couldn’t say no when asked (46.3%).

Respondents were asked to identify the reasons they continue to volunteer. They unanimously agreed that 4-H leaders continue volunteering for the following reasons: “liked helping people” (100%), “they continued to receive satisfaction of seeing youth succeed” (100%), and “continued to want to teach the youth” (100%). The other reasons 4-H leaders continue to volunteer included: “continued to learn new things” (97.5%), built “positive mentoring relationship with the youth” (95.3%), “continued to derive personal satisfaction when working with youth” (95.2%), “enjoyed volunteering in their spare time” (95.1%), and “their children were involved” (92.7%). An overwhelming majority also agreed they “felt appreciated by youth” (85.7%), “enjoyed taking on responsibility” (82.9%), and “they were asked to continue volunteering” (82.9%) were among the top 10 reasons why 4-H leaders continue to volunteer.

The reasons least likely to influence the decision to continue to serve as a 4-H volunteer were: “continuing to gain skills which might lead to employment” (34.1%), “can’t say no when asked” (48.8%), “receive status in the community” (48.8%), “liked the recognition associated with being a volunteer” (56.1%), and enjoyed “community service benefits” (65.9%).

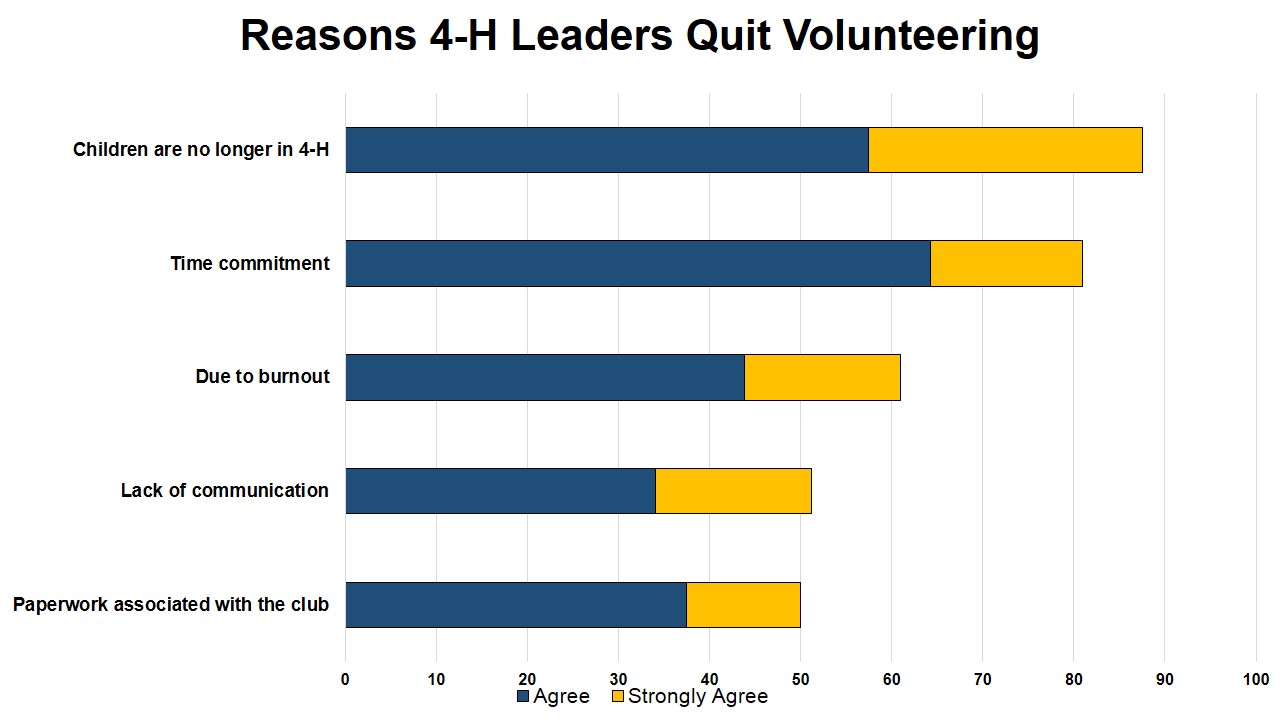

Respondents were asked to identify the reasons they had quit volunteering and/or reasons they considered quitting. The number one reason respondents believe 4-H leaders quit volunteering was because their children were no longer in 4-H (87.5%). Other reasons to quit volunteering included time commitment required (81.0%), burn out (61.0%), lack of communication (51.2%), and paperwork associated with the club (50.0%).

Conflicts with youth were not seen to be a strong factor in the reason 4-H leaders quit (12.2%). Too much travel (21.9%), cost involved (22.5%), lack of self-improvement opportunities (23.0%), and lack of recognition (26.8%) were rated lowest as factors which caused 4-H leaders to quit.

Respondents were asked to identify problems they face as a 4-H volunteer. The items ranked highest as perceived problems by leaders were: burn out (68.3%), meeting conflicts (67.5%), and lack of information (60.5%). The items not considered problems 4-H leaders face in the program were lack of self-improvement opportunities (17.1%), conflicts with youth (20.0%), cost involved (27.5%), conflicts with parents (30.0%), and too much responsibility (30.0%).

Nearly 80% of the respondents considered the County 4-H program to be effective or highly effective. The respondents preferred methods of receiving information were newsletters (59.5%), phone calls (47.6%), and e-mails (45.2%). Texting was only preferred by one person (2.4%).

Respondents were asked to indicate what kind of support was needed for 4-H leaders. Support needed for 4-H leaders included new leader orientation (61.9%), available ongoing leader training (73.8%), and awareness of leader resources and curriculum and materials available (73. 8%). Volunteer leader weekend and county leadership training as well as volunteer orientation were all considered beneficial for 4-H leaders.

Discussion

4-H leaders volunteer and continue volunteering for intrinsic reasons such as liking to help people, to benefit the community, teach youth, and the satisfaction of seeing youth succeed. Although research has been conducted previously about 4-H volunteer recruitment and retention, this study looks at factors which influence 4-H volunteers in Appalachia.

4-H leaders extrinsic reasons were not primary reasons leaders volunteer. Skills for employment opportunities, receiving status in community, and recognition were ranked at the bottom of reasons people volunteer or continuing to volunteer. This was consistent with research conducted by Cobley (2008), White and Arnold (2003), and Kerka (2003). Although, to the contrary, Stillwell, Culp, and Hunter (2010), believe recognition is one of the key volunteer retention methods and have created a recognition program model. Davis (2000) also believes retention is at its highest when recognition is given.

The number one reason why 4-H leaders no longer volunteer, is because their children are no longer in 4-H. This was consistent with findings by Van Horn, Heasley, and Presley (1985) and Culp and Schwartz (1999). 4-H leaders who feel they are no longer needed or made to feel they are not a part of a team, through lack of involvement in planning and decision making, tend to leave the organization. This was consistent with the findings of Culp and Schwartz (1999).

Burnout tends to be seen as the number one reason why 4-H leaders in the study quit volunteering. This was opposite of Skoglund’s (2003) research of turnover being for reasons such as volunteers feel alone in their volunteer work.

Ongoing leader training and awareness of leader resource curriculum and materials are believed to be beneficial and could lead to higher retention of 4-H leaders. This was consistent with Kerka (2003) and the Volunteer Research, Knowledge, and Competency Taxonomy for 4-H Youth Development developed by Culp, McKee, and Nestor (2008).

Extension professional development programs need to be offered to train agents in how to manage volunteers. An increasing amount of the agent’s time is spent recruiting, training, motivating and retaining volunteers. While many agents are trained to work with youth, they lack the knowledge of best practices in working with adult volunteers. The study findings suggest that agents need to explore various means of communication to improve the retention of volunteers. With social media readily available in most areas, agents should consider using social media venues such as Facebook pages dedicated to county 4-H volunteers to post announcements of upcoming events, tips of the trade, share ideas and allow interaction among volunteers. Online social media opportunities may help to retain leaders who may no longer feel they are a part of the team as their network declines once their children age out of 4-H. Agents and states need to consider developing and offering online trainings for volunteers and develop ways to increase retention of volunteers. By focusing training to build skills and confidence in leaders while rewarding their efforts to make a difference will help with the retention of leaders. By participating in these trainings, leaders may feel needed and become a part of a team that makes a difference with 4-H youth.

References

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., & Sorensen, C. (2010). Introduction to Research in Education (8th ed.). (pp. 392-398). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). Volunteering in the United States, 2010. United States Department of Labor. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/volun.nr.o.htm

Cobley, J. (2008). Who is volunteering for the Maine 4-H Program? Journal of Extension.

Eagan, S., Nestor, P., Seita, T., & Townsend, C. (n.d.). Five keys to effective volunteer program development. WVU Extension Service.

Culp, K., III., & Schwartz, V. J. (1999). Motivating adult volunteer 4-H leaders. Journal of Extension 35(3) Retrieved from http://www.joe.org/joe/1999february/rb5.php

Culp, K., III., McKee, R., & Nester, P. (2008). Volunteer Research, Knowledge & Competency Taxonomy for 4-H Youth Development. Retrieved from http://www.uwex.edu/ces/4h/resources/mgt/documents/VRKC3.pdf

Davis, K. (2000). Factors influencing the recruiting and retaining of volunteers in community. Eric Publications. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED450243.pdf

Dillman, D. A. (2007). Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). New Jersey: John Wiley.

Eagan, S., Nestor, P., Seita, T., & Townsend, C. (n.d.). Five keys to effective volunteer program development. WVU Extension Service.

Independent Sector. (2010). Value of volunteer time. Retrieved from http://www.independentsector.org/volunteer_time

Kerka, S. ( 2003). Volunteer development practices application brief No. 26. Eric Clearing House on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education. Columbus, OH Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED475111.pdf

McCurley, S., & Lynch, R. (2006). An introduction to volunteer management. Essential Volunteer Management (2nd Edition). London. Retrieved from http://www.dsc.org.uk/portal_products/products/002658/attachments/Look%20Inside%20-%20Essential%20Volunteer%20Management.pdf

Post, J. A. (2007) Attitudes of 4-H Club leaders Toward Volunteer Training in West Virginia. Unpublished master’s thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia. Retrieved from http://wvuscholar.wvu.edu:8881/R?RN=28763297

Robinson, J. P., Shaver, P. R., & Wrightsman, L. S. (1991). Criteria for scale selection and evaluation. In J.P. Robinson, P.R. Shaver, & L.S. Wrightsman (Eds.). Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 1-16). New York: Academic Press.

Skoglund, A.G., (2003). Do not forget about your volunteers: A qualitative analysis of factors influencing volunteer turnover. Health and Social Work, 31(3). Retrieved from http://www.rockinworship.com/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderfiles/VolunteerTurnover.pdf

Stillwell, M., Culp, K., & Hunter, K. (2010). The volunteer recognition program model: providing volunteer recognition throughout the year. Journal of Extension 48(3). www.joe.org/joe/2010june/H2.php.

Townsend, C. (2004). West Virginia Extension Service – here to serve you. Volunteer Visions. West Virginia University Extension Service. Retrieved from http://4hyd.ext.wvu.edu/r/download/43338

Van Horn, J., Heasley, D., & Preston B. (1985). Shedding the cocoon of status quo. Journal of Extension, 23(1). Retrieved from http://www.joe.org/joe/1985spring/a1.php.

Vettern, R., Hall, T., & Schmidt, M. (2009). Understanding what rocks their world: motivational factors of rural volunteers. Journal of Extension 47(6). Retrieved from www.joe.org/joe/2009december/a3.php

White, D. J., & Arnold M. E., (2003). Why they come, why they go, and why they stay: Factors affecting volunteerism in 4-H programs. Journal of Extension, 41(41). Retrieved from www.joe.org/joe/2003august/rb5.php

4-H Youth Volunteerism Team. (2004). This is 4-H. Volunteer Visions. West Virginia University Extension Service. Retrieved from http://4-hyd.ext.wvu.edu/r/download/43349