Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 7, Issue 1 - May, 2014

Bilingual Workshops on a Systems Approach to Plant Disease Prevention in Oregon Nurseries

- Santamaria, L., Nursery Crops Extension Specialist & Assistant Professor, Oregon State University, North Willamette Research & Extension Center

Uribe, G., Education Program Assistant, Oregon State University, North Willamette Research & Extension Center

ABSTRACT

A workforce that is well trained and knowledgeable in disease recognition and prevention is key to having a successful disease management program in any crop production operation. Workers need training to identify problems and continue being updated on best management practices. Also, teaching and training resources must be appropriately designed for the target audience. The Oregon nursery and greenhouse industry is among the largest in the country and there is a need for the predominantly Hispanic workforce to receive training in many of the new sanitation and disease prevention practices being developed. The goal of this program was to provide background information and training on a systems approach to disease prevention and management targeting the Spanish-speaking workers in Oregon nurseries and to evaluate change in knowledge as a result of participation in training workshops. This was achieved using a pre- and post- workshop evaluation survey. Evaluation results show high ratings from participants for the overall value of these workshops and a significant increase in their understanding of key concepts provided during the trainings.

INTRODUCTION

The nursery, greenhouse, and tree farm industry in Oregon was the state’s first billion-dollar farm gate agricultural sector in 2007 (Oregon Agriculture & Fisheries Statistics, 2008) but, the Great Recession produced significant change. Between 2007 and 2010, more than 30% of the industry’s farm gate value was lost, many nurseries closed, and the workforce was reduced (Oregon Agriculture & Fisheries Statistics, 2011). However, production value has been on the rise, and by 2012, the industry had recovered modestly to a farm gate of $745 million (Oregon Agriculture and Fisheries Statistics, 2013). The total number of nursery/greenhouse operations in the state remained at 1,800 during 2010 with 20,600 full- and part-time employees (Oregon Nursery and Greenhouse Survey, 2010). Historically, large portions of the front-line nursery employees in Oregon have been Hispanic workers (U.S. Census Bureau; Mathers, 2003). Current estimates from several of the participating nurseries indicate their Hispanic worker composition is near or above 90% (personal communication).

Disease management in any plant production system is critical for success. Proper identification, monitoring, prevention, and sanitation are essential steps for successful disease management strategies. Additionally, as more knowledge about diseases and how they spread becomes available, changes in production practices are needed. New methods to mitigate losses resulting from diseases in nursery and greenhouse settings are being continually developed and assessed by researchers using scientific approaches. The results and newly developed methods are then disseminated to the industry (e.g. Griesbach et al., 2012). Resources such as these can be of great help, but in order for them to be successfully implemented, the information needs to make its way to the front-line workers. The Hispanic workforce is often the front line in identifying problems in nurseries. They can play a greater role to improve production, but only if they are properly trained and they know what they are looking for.

In Oregon, it has been the authors’ experience that many of the nursery laborers do not speak English fluently and may also lack a basic understanding of plant biology and science. The language barrier can hinder and prevent the adoption of new disease prevention strategies and practices. Additionally, in many cases, the workers may not have high school educations (U.S. Census Bureau, Quarterly Workforce Indicators Data). Even when managers have access to reference materials, many of the details can get lost in translation when attempting to convey it to their workers. When information in Spanish is available, literal translations of technical materials are still difficult to follow, especially for anyone without an educational background in botany or horticulture.

The goal of these workshops was to design and deliver nursery disease management information in English and Spanish directly to the workers in a concise and straightforward manner that would allow them to make use of the information and apply it in their workplace. The information presented consisted of preventative methods in the context of a systems approach that will help minimize the risk of introducing new diseases. Participants learned to identify critical control points specific to their production system. As discussed elsewhere (Griesbach et al., 2012; Parke & Grünwald, 2012), the systems approach focuses on prevention, rather than crisis management. Therefore, taking proper precautions was emphasized.

Included in these workshops was a brief introduction to microorganisms, their ubiquity, and methods of dispersal. Large portions of the workforce lack high school degrees so for many of the participants, this was their first exposure to concepts of biology, microbiology, and plant pathology. For example, participants were introduced to the concepts of the disease triangle and disease cycles. Another goal was to drive home the importance of sanitation and the ease with which pathogens can be inadvertently spread. To help them visualize, participants were given potato dextrose agar culture plates to allow them to sample surfaces that they thought were clean.

After the trainings, many of the workers expressed that understanding the background and theory behind sanitary protocols compelled them to follow those procedures because the procedures no longer seemed arbitrary. The participants were also able to identify other critical control points that needed improvement in their nurseries because of their increased understanding of these concepts. So, as the nursery and greenhouse industry emerges from difficult times, there is keen interest to control costs and improve production efficiencies. Many nurseries see an opportunity to provide worker training as a way to prepare their workforce to play a larger role in helping their enterprises flourish in the future.

METHODS

Workshops & Data Collection. Nine, nursery systems approach workshops took place between December 2012 and August 2013 at six nurseries in the Willamette Valley. Workshops were offered in English or Spanish, but only one nursery requested a workshop in English. The workshop in English was for the managers and growers from a nursery who wanted to be familiar with the information that their workers would be receiving. Because the purpose of that specific workshop was not to train the participants, data collected from that workshop was not used in our analyses.

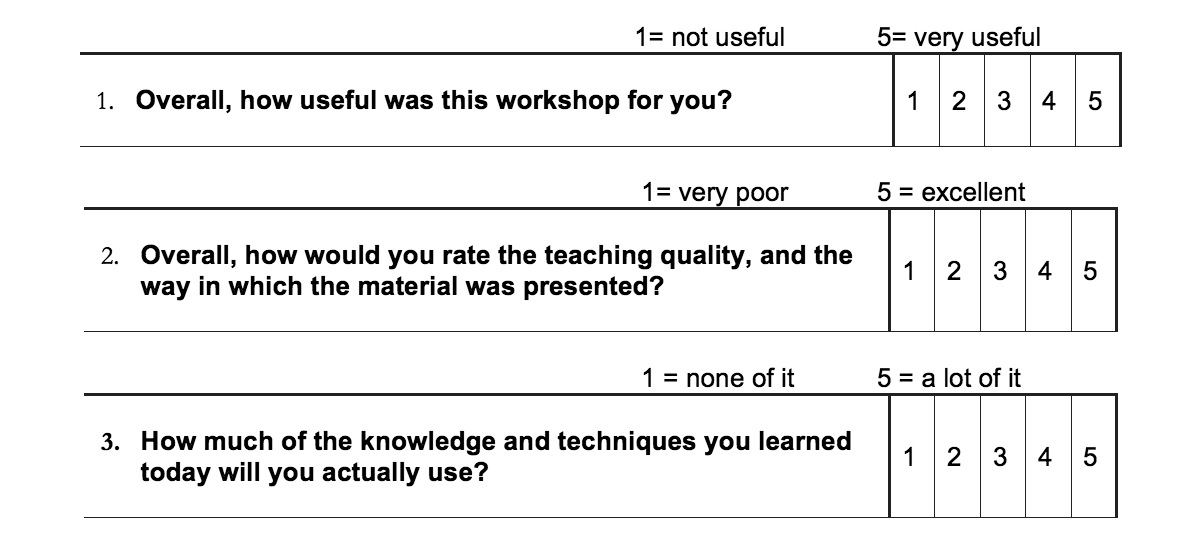

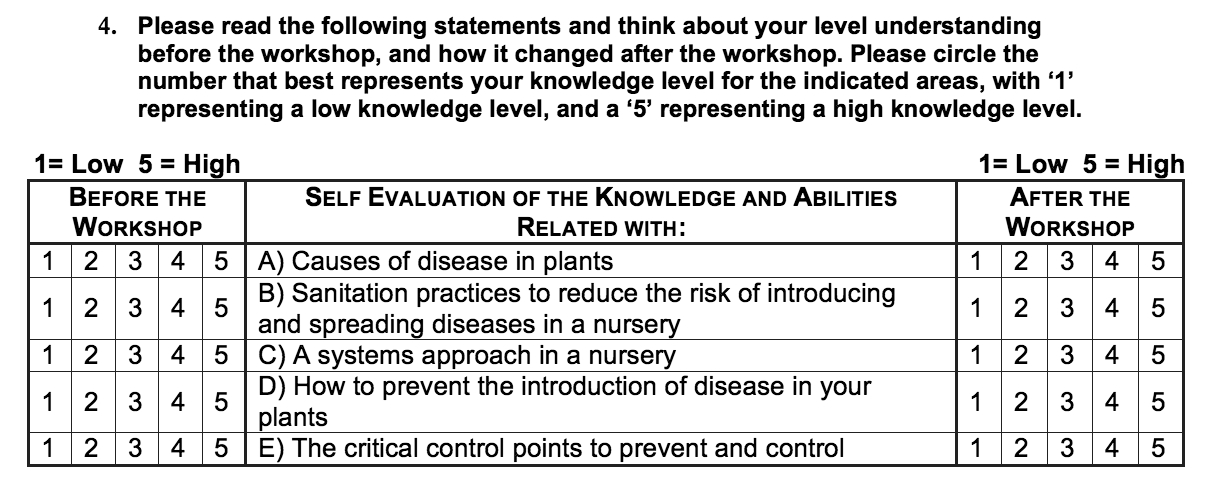

The workshops ran for three hours. A total of 102 nursery workers participated. Each of the workshop participants was provided a voluntary evaluation form. The first part consisted of an overall workshop evaluation in which participants evaluated the workshop based on three questions (Figure 1). The second part of the survey was a self-evaluation of how knowledgeable the workers felt about topics discussed in the workshop (Figure 2).

Basic biological concepts about pathogens and epidemiology were presented, as well as activities that allowed the participants to discuss ideas with coworkers from different areas of the production process, allowing them to interact with each other. Once the workshop was completed, the participants were asked to re-evaluate how knowledgeable they felt about those same concepts.

Figure 1. Overall workshop evaluation format and grading scale as presented to the participants. The actual form was presented to the participants in Spanish.

Figure 2. Pre- and post-workshop self-evaluation format and grading scale as presented to the participants. The participants’ form was in Spanish.

Statistical Analyses. Means and standard deviations were calculated for each of the workshop evaluation questions from the first part of the survey (Figure 1). A different approach was taken to assess the self-evaluation portion of the survey (Figure 2). In some instances, participants did not return their surveys, or the surveys were incomplete, with responses in only the pre- or post-workshop categories for some, or all of the statements. In such instances, those data were excluded from analysis.

Each of the statements evaluated in the pre/post survey was analyzed separately using the statistical analysis program R (R Development Core Team, 2008), beginning with a test for normality of the data using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data was not normally distributed, so a paired Mann-Whitney test was performed to test whether the corresponding pre- and post-workshop rating means were significantly different. Significance was interpreted at 99% confidence.

RESULTS & DISCUSSION

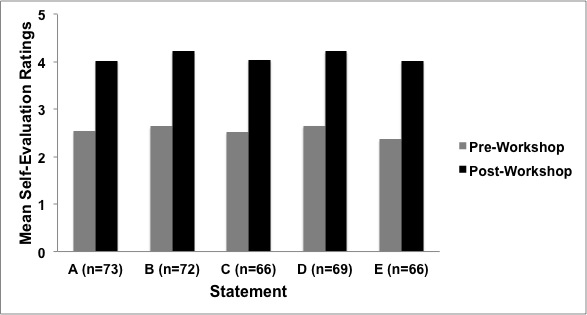

Figure 3. Pre- and post-workshop mean ratings in a side-by-side comparison for the participant self-evaluation portion of the workshop. All statements were evaluated on a 1-5 scale with ‘1’ representing a low knowledge level and ‘5’ representing a high knowledge level. All post-training mean rating changes were statistically significant (p≤0.01). Statement A: Causes of disease in plants; B: Sanitation practices to reduce the risk of introducing and spreading disease in a nursery; C: A systems approach in a nursery; D: How to prevent the introduction of disease in your plants; E: The critical control points to prevent and control diseases.

The results from the first part of the evaluation show that, overall, the workshops received good ratings from the participants. Rating means for each of the three questions were 4.5, 4.5, and 4.3 for each of the statements, respectively. The authors feel confident that the workshops were well received, the educational design and materials appropriate for the participants, and that concepts discussed during the workshops can be applied in the workplace. Analysis of responses for the second part of the evaluation shows that for each of the self-evaluation statements there was a significant increase in the participants’ self-reported level of understanding and knowledge for the corresponding concepts (Figure 3). In each case, ratings rose from approximately 2.5 to 4.0. Many participants expressed that they have a better sense of what causes diseases in plants, the role of sanitation in disease prevention, and a systems approach for nursery and disease management. They had been unaware that many things could be done to prevent diseases and that pesticide application is not the only option for disease management.

Our initial findings, presented here, show the promise of workforce training in Oregon’s nursery industry. It is evident that workers feel more empowered by the knowledge they acquire and understand that immediately reporting to their supervisors any suspicious symptoms allows for an early response and prevention. Also, it has become clear that merely having information available is not enough, even if it is in Spanish. The basic understanding of plant and pathogen biology, and the operational processes within their production system must be presented in a manner appropriate for the target audience.

The authors are interested in following up with the nursery managers at these training locations to determine how the workshops have affected their workers’ behavior. It is one thing to gauge whether the workers are more knowledgeable, and another to measure behavioral changes and improvements in disease management. For example, do managers see that improved understanding and knowledge lead to better work practices, reduced disease incidence, and better production efficiency? One must also keep in mind that to have marked improvements, the workers will need follow-up support from management in order to change or develop protocols for production that allow them to implement what they have learned.

Ideally, the next step would be to produce quantitative data in terms of how much these trainings have affected behavior, and consequently, production. For example, decreases in pesticide use after trainings, if behavioral changes were adopted, would be a way to gauge training impacts due to improved disease prevention. Cost savings will also allow the industry to put monetary value on the benefit of educating their workers. For now, we can only rely on the self-reported, qualitative responses of nursery owners and supervisors. Although the analysis of this information will require considerable effort, informal conversations with nursery managers already indicate their desire to expand the workforce training opportunities for their employees. Besides introductory training modules described here, managers see the need for more advanced, in-depth, and targeted education.

Based on our conversations with many of the participating workers, we came to understand that they had been able to recognize many of the signs and symptoms associated with diseased plants prior to the trainings. However, understanding why it was important to quickly isolate those plants, and to communicate their findings with their supervisors was much more clear now that they understand what pathogens are and how they disperse. The authors would also like to note that many of the participants expressed a realization of how much more there was still to learn on the subject.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Oregon Department of Agriculture and their Plant Health Program provided funding for the training workshops - award ODA-3138. We would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Michael Bondi, director of the Oregon State University North Willamette Research and Extension Center for his support in the development of this program, Mike Knutz, Yamhill County, Oregon State University Extension Service, Christine C. Hayes, and our anonymous reviewers for their valued feedback, and all the nurseries and workers that have participated.

LITERATURE CITED

Parke, J. L. and N. J. Grünwald. 2012. A systems approach for management of pests and pathogens of nursery crops. Plant Disease 96:1236-1244.

Griesbach, J.A., Parke, J. L., Chastagner, G.C., Grunwald, N.J., Aguirre, J. 2012. Safe procurement and production manual: a systems approach for the production of healthy nursery stock. 2nd ed. Oregon Association of Nurseries, Wilsonville, OR. 105 pp.

Mathers, H.M. 2003. Technical information requested by Hispanic Nursery Employees- Survey results from Oregon and Ohio. Journal of Environmental Horticulture 21:184-189.

Oregon Field Office National Agricultural Statistics Service United States Department of Agriculture. 2013. Oregon Agriculture & Fisheries Statistics. http://www.oregon.gov/ODA/docs/pdf/pubs/2013_agripedia_stats.pdf

Oregon Field Office National Agricultural Statistics Service United States Department of Agriculture. 2011. Oregon Agriculture & Fisheries Statistics. http://www.oregon.gov/ODA/docs/pdf/pubs/2011agripedia.pdf

Oregon Field Office National Agricultural Statistics Service United States Department of Agriculture. 2008. Oregon Agriculture & Fisheries Statistics. http://www.oregon.gov/ODA/docs/pdf/pubs/2008agripedia.pdf

Oregon Field Office National Agricultural Statistics Service United States Department of Agriculture. 2010. Oregon Nursery and Greenhouse Survey. http://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Oregon/Publications/Horticulture/2010_nursery.pdf

R Development Core Team. 2008. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, http://www.R-project.org

U.S. Census Bureau. 2013. Quarterly Workforce Indicators Data. Longitudinal-Employer Household Dynamics Program. http://www.vrdc.cornell.edu/qwipu/