Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 8, Issue 1 - June, 2015

Women Are From Venus: Unique Programming Needs & Challenges of Women Farmers

- Blazek, J., Dairy & Livestock Agent, University of Wisconsin-Extension, Dane County

Wantoch, K., Agriculture Agent Specializing in Economic Development, University of Wisconsin-Extension, Dunn County

Sterry, R., Agriculture Agent, University of Wisconsin-Extension, St. Croix County

Kirkpatrick, J., Outreach Specialist, University of Wisconsin-Extension

ABSTRACT

Annie’s Project is a successful educational program that focuses on risk management strategies and tools for women farmers. Traditional Annie’s Project audiences, who own or manage dairy and beef livestock enterprises and are farming with a male partner, are well served by the program, however, a growing number of beginning and value-added farms with a female principal operator requires a new approach. Wisconsin has 7,346 farms identifying a woman as the principal operator (2012 USDA Census of Agriculture), which places the state fourteenth in the nation for the number of women principal operators. To meet the educational needs of beginning farm women and those considering an alternative agriculture enterprise, Wisconsin educators adapted the Annie’s Project curriculum for Value-Added and Beginning Farm Women. The results of the six-week series show that a different approach to workshop planning and curriculum development is necessary when working with women farmers compared to their male counterparts.

Introduction

Annie’s Project is a successful educational program that focuses on risk management strategies and tools for women farmers. The program was developed by Ruth Hambleton, University of Illinois Cooperative Extension, in 2003 and has been delivered in over 34 states since. Annie’s Project is designed to bring women farmers of varying experience levels together to learn from not only the instructors, but also each other. Participants meet between four and six times for approximately three hours. In 2004, the staff at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Dairy Profitability (CDP) adapted Annie’s Project to the needs of Wisconsin women farmers, emphasizing dairy and livestock issues, and has since reached approximately 270 women farmers. Recent adaptations of the Annie’s Project curriculum for value–added and beginning farmers meets the needs of an even wider population of women farmers.

Demographic data indicates a majority of participants in the traditional Annie’s Project program series own or manage dairy and beef livestock enterprises and are farming with a male partner. This audience is well served by Annie’s Project; however, a growing number of beginning and value-added farms with a female principal operator requires a new approach. There are 7,346 Wisconsin farms identifying a woman as the principal operator of the farm (2012 USDA Census of Agriculture), a 20 percent drop from 2007. This places Wisconsin fourteenth in the nation for the number of women principal operators and ninth (tied with New York) in the nation for growth in this population. Census data indicates Dunn, Pierce, Polk and St. Croix Counties in Northwest Wisconsin have 718 farms with a female identified as a principal operator. The average size of Wisconsin farms with women as principal operators is 94 acres, as compared to an overall average Wisconsin farm size of 194 acres. Research indicates that farms operated by women are on average smaller in acres and sales when compared to all Wisconsin farms. These farms are more likely to have limited resources and consider alternative and/or direct marketing enterprises. Beginning farm women and those considering an alternative agriculture enterprise have different educational and risk management needs compared to established farmers and commodity producers.

While traditional women farmer programs have been considered by participants to be “fluffy” in nature, the Annie’s Project program has direct application to a farm woman’s farm by providing useful, research-based information and resources. In response to the large number of women serving value-added and alternative markets, the CDP partnered with the UW-Extension Agricultural Innovation Center (AIC) in 2009 to develop a curriculum specifically adapted to the needs of value-added and beginning women farmers. Organizers gathered information from an advisory committee, who emphasized the need for business planning, financial and tax management, food safety and handling regulations, and accessing agency/organization resources. Two pilot sessions of this six-week curriculum was offered in Dane County (Madison, WI) and Walworth County in 2010. This curriculum was further adapted in 2013 to assist farm women who were just starting or were direct-marketing their farm products in Northwest Wisconsin.

Materials and Methods

In 2013, staff from the CDP and UW-Extension further adapted the Annie’s Project curriculum for value-added and beginning women farmers in the Northwest region of Wisconsin. This six week program was developed to address the risk management education needs of this rapidly growing population of women farmers in Dunn, St. Croix, and Polk Counties. The curriculum included topics related to the five areas of risk management: production, marketing, financial, legal, and human resource. The following topics comprised the curriculum:

- personality traits and skills,

- assessing farm business feasibility,

- conducting and analyzing market research,

- writing a farm business plan,

- farm business structure and liability issues,

- farm financial and tax management,

- state and federal regulations and safe food handling,

- and additional resources for land access, financing, and grant opportunities.

Additional items were added to the curriculum to facilitate the women learning from each other and other women farmers. The local Agriculture Agents felt that it was important to include during the session lunch breaks, an opportunity to feature a local farmer to discuss their value-added agriculture enterprise and share their stories as it related to session topics.

This six-week curriculum titled, Annie’s Project for Value-Added and Beginning Farm Women, was offered in January and February 2013 in Baldwin, WI, which was a central location between Dunn, Pierce, Polk and St. Croix Counties in Northwest Wisconsin. The sessions were held on Wednesdays from 10am to 3pm. The program team and primary organizers consisted of Agriculture Agents, Jennifer Blazek, Katie Wantoch, and Ryan Sterry, from three of the four northwestern counties, along with assistance from Joy Kirkpatrick, from the Center for Dairy Profitability. In order to facilitate the coordination of this program, the six days were split equally among the three educators, whose responsibility was then to organize the agenda and speakers for those days.

A total of 18 speakers provided information, resources and learning activities during the course of the six-week program. Presenters included the three program organizers, a UW-Extension Family Living Agent, a UW-Extension Community Resource Development Agent, a UW-Extension 4-H Youth Development Agent, a UW-Extension Business Management Specialist, two Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade & Consumer Protection employees, a Farm Service Agency loan officer, an AgStar (Farm Credit) loan officer, one certified public accountant, one attorney and six local value-added agriculture producers. Speakers were a mixture of male and female, chosen primarily for their expertise and ability to teach. Only in selecting the local value-added agriculture producers did the organizers try to identify women farmers. In the end, five out of the six farmer speakers were women.

Team members placed a high value on communication, not only between the organizers and participants, but among the participants themselves. Networking was encouraged by providing a half hour of time before each session and utilizing a class email listserv. The listserv provided team members an efficient means of communication to remind participants about homework, provide additional resources, continue discussions from the session, and inform participants of any changes to the sessions due to weather conditions.

Instructors were encouraged to make the sessions interactive and participatory, rather than relying on lectures. To accommodate different learning styles, instructors used small group work as well as worksheets and assessments. Visuals, in the form of PowerPoint presentations, video clips, and images were also extensively used by instructors in order to share information. Homework assignments were also encouraged and follow-up was provided during the following session.

Promotion of the workshop series included emails to various listservs, news articles, and newsletter mailings. The program was mentioned during an interview for Wisconsin Public Radio’s local Newsmakers program as well as interviews with local radio stations. Each educator advertised the program in their own counties and also within the Northwest region of the state.

Results

There was overwhelming interest in the program series, with 23 people registered and several people on a waiting list. A hundred percent of the participants were women farmers from six counties and two states.

Evaluation of the program and the participants was emphasized before, during, and after completion of the program series. Participants were mailed a baseline pre-workshop survey prior to attending the first session of the series. Basic demographic questions were asked in addition to questions discerning the risk management tools or strategies participants were already incorporating into their farm business. Twenty-one baseline surveys were returned.

Demographics of the Participants

The average range of age of the participants were 45-54 years old. Five participants were in the range of 34 years old and younger, and only three participants between the ages of 35 and 44 years old. This indicates a majority of the participants are younger than Wisconsin’s average age for female principal farm operators of 57 years (2012 USDA Census of Ag). The respondents listed a wide range of farm businesses when asked to describe their “type of farm”; although participants could be split evenly between livestock and crop or vegetable enterprises. As Figure 1 indicates, the participants owned more land than managed; however, three of the respondents did not currently own any land.

Figure 1. Participants' Acres Owned and/or Managed

Many participants found it difficult to answer the risk management questions in the survey since many of the women were in the beginning stages of their agriculture enterprises. Seventy-six percent of the participants had been farming for less than 10 years. This is a little higher than the state average, where only 21 percent of female principal operators had been farming for less than 10 years.

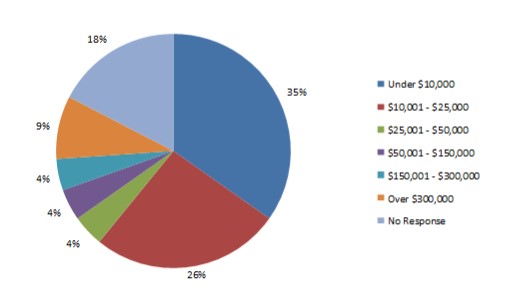

As depicted in Figure 2, 61 percent of the respondents receive $25,000 or less gross income from their farm annually. In comparison, 85 percent of WI farms with women principal operators reported $24,999 or less of annual farm income (2007 Census of Agriculture). Eighteen percent provided no response and it could be inferred that they do not receive any income from a farm business, or were just unwilling to report their income. Twenty-one percent receive between $25,001 and $300,000 gross income annually, which interestingly, is greater than the state average of 15 percent. Nine percent of the participants receive more than $300,000 a year from their farm operations.

Figure 2. Participants' Annual Gross Farm Income

When asked about current business structure for their farming enterprise, 43 percent listed “sole-owner” as their form of business; 13 percent had formed partnerships, another 22% have their business as a limited liability company (LLC) or corporation and the remaining 22% either had other structures or did not respond.

Participants’ number one concern about their farming business was related to financial management. In response to the question: “Your number one concern about your farm business is,” participants answered, in highest ranked order: start-up costs, managing finances, profitability and financial sustainability. Not surprisingly, when asked about their goals or reasons for attending the workshop series, answers about financial management and business feasibility were again the most common answers.

Program Evaluation

Organizers felt it was important to “check-in” with the group to ensure educational needs were being met for the majority of the participants. The program was evaluated twice during the six sessions by written evaluations, and twice after the course via online and verbal feedback gathered from the group. Verbal feedback provided organizers with information about the need for more interactive sessions, activities and/or case studies.

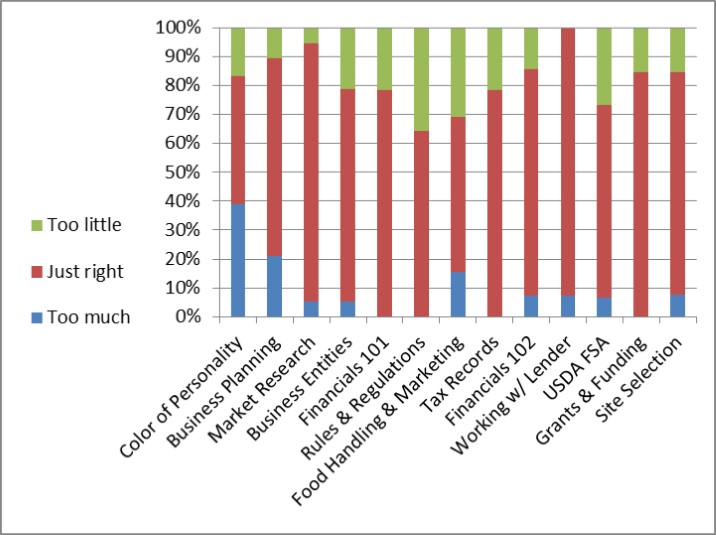

Participants were asked to evaluate the time spent on the topics during the class, and whether too much, too little or just the right amount of time was spent on each topic area. Figure 3 shows that overall the right amount of time was spent on all of the topics covered during the class. The highest rated topic, in which the participants wanted more information, was Rules and Regulations. The lowest rated topic, meaning less time could have been spent on it, was Discover the Color of Your Personality.

Figure 3. Evaluation Results on Time Spent on Each Topic

Organizers contacted the participants both at six months and at one year after completion of the program. Participants were asked if they had used any of the information or resources from the topics covered during the six week series in their farm operations and businesses. The top three topics reported by the participants as most used after the series were:

- Market research

- Business planning

- Rules and Regulations

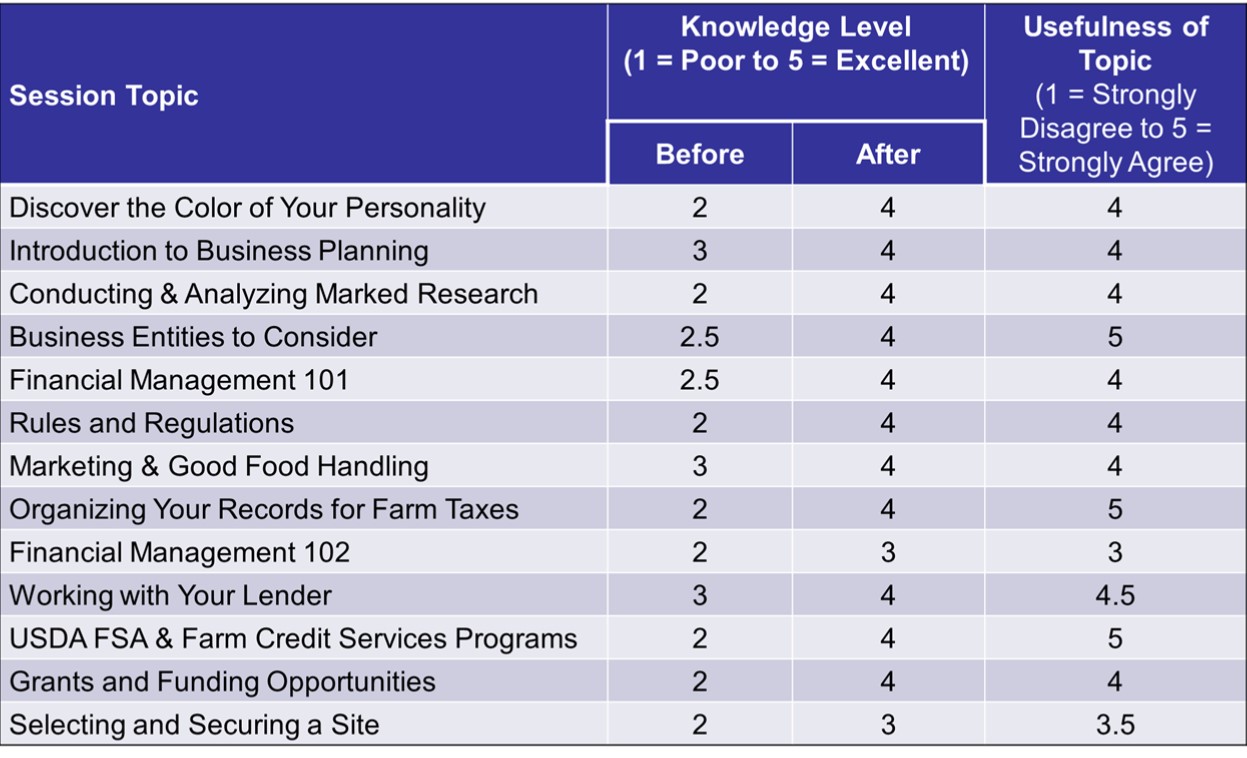

Not surprisingly, these were also topics that addressed the concerns expressed in the baseline survey at the beginning of the six-week series. Interestingly, participants rated these topics slightly lower in terms of usefulness during the series. Figure 4 demonstrates both the participants’ change in knowledge level before and after the program and also the perceived usefulness of each topic (1 through 5 Likert scale). Business Entities to Consider, Organizing Your Records for Farm Taxes, USDA FSA & Farm Credit Services Programs, and Working with Your Lender were the most useful topics. There was also a significant increase in knowledge reported by the participants for the majority of the topics presented.

Figure 4. Evaluation Results on Knowledge Level and Usefulness of Each Topic

Participants were asked if they had developed their business plan or moved forward with their enterprise plans since attending the program. Eighty-five percent of participants indicated that they have started, had a portion done or have completed their plans. Time and funding were the biggest barriers to their progress. One respondent commented, “[I] changed my business plan to include some things that I had not thought of until the project workshop.”

An unintended positive outcome was an increase in confidence among the participants. One woman felt the information presented on tax records was very beneficial as it helped her to better organize and manage her records, even improving her relationship with her tax accountant: “[I] established a process to manage records and started using QuickBooks (financial software program). [I] received compliments from my tax accountant about my preparation of materials. He expressed that a number of farm clientele could take tips from me.”

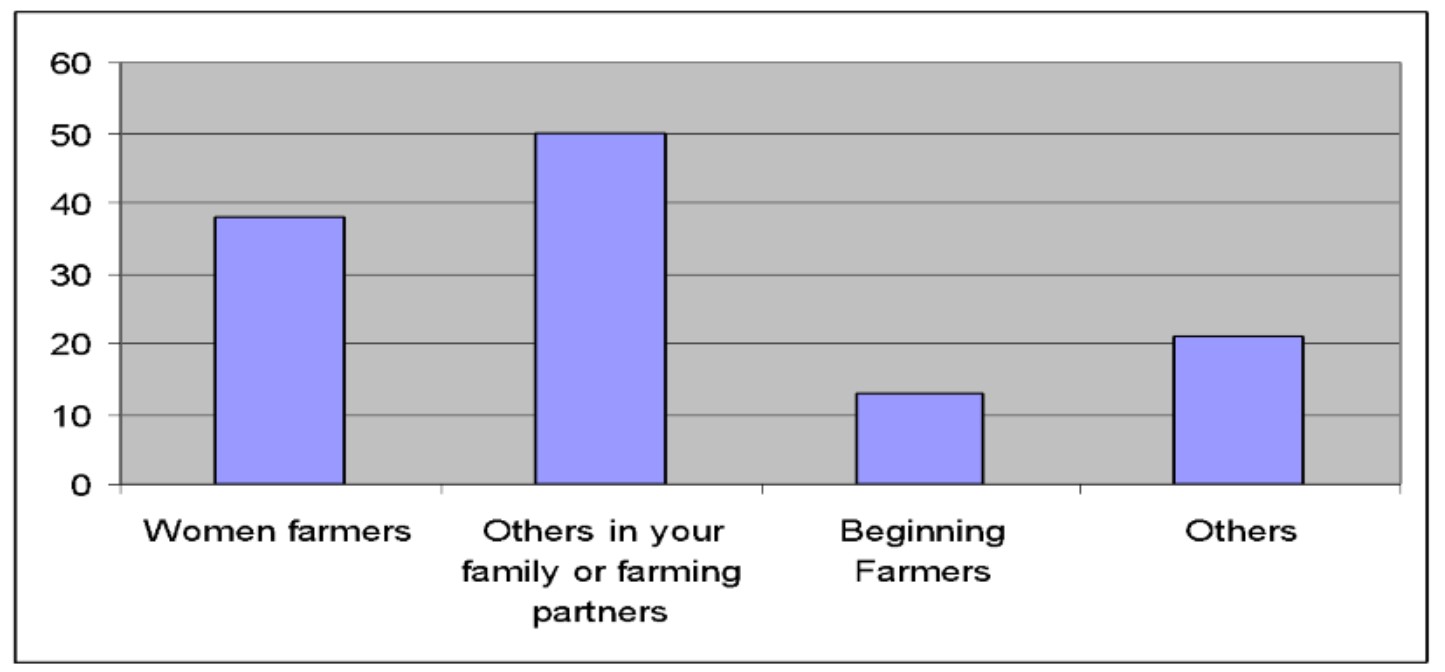

Organizers were also interested to know if participants shared the information that they had learned during the series with others. Figure 5 illustrates the number of people who have received information and resources from Annie’s Project participants. Participants shared their knowledge with a total of 51 beginning and women farmers. Half of the participants continued to network with at least one other program participant. Most women kept in contact through email, although about 57 percent met in-person with another participant, on their own. Program organizers coordinated a Reunion during the Fall of 2013 and again in 2014 for participants to continue networking. One participant indicated, “4-5 people from class continue to network for farm and business advice.”

Figure 5. Participants' Sharing Knowledge with Others

Program Cost Analysis

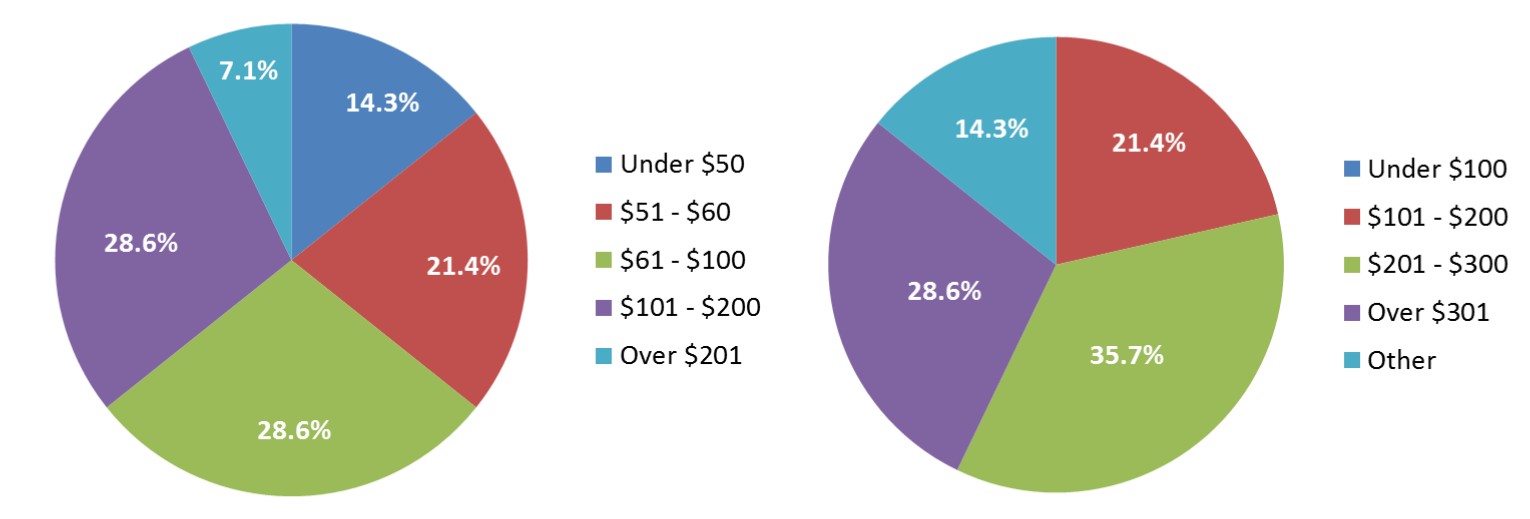

Wisconsin’s Annie’s Project targeting beginning and value-added women farmers was heavily subsidized by a USDA Risk Management Agency grant, financial support from AgStar Financial Services (Farm Credit), Annie’s Project national program agency, and staff time from CDP and UW-Extension. Cost analysis in other states offering Annie’s Project programs estimate the actual cost to provide a six week program is approximately $300 per participant. Participants were given this ‘true-cost’ information and asked, “After going through the program: a) what dollar value would you place on it and b) what would you be able/willing to pay for the six week course.” Figure 6 shows a pie chart of participants’ answers to each of the questions. Participants valued the program (answers to question a) at $310 (averaged), with answers ranging from $120 to $500. Their averaged response to what they are able/willing to pay, with many participants emphasizing the “able” portion of the question, was $115, with ranges from $40 to $300.

Figure 6. Dollar Value Placed on Program Series (left) and Amount Able/Willing to Pay for the Program Series (right)

Discussion

The waiting list for this workshop series and the interest expressed by UW-Extension educators and residents across the state demonstrates the need for these types of programs for beginning women farmers. Annie’s Project provides approximately 24 hours of instruction, and invaluable access to agency and organization resources. Eighty-five percent of participants felt that it was very important to offer programs especially designed for women in agriculture.

- “Women tend to have different perspectives and problems that are sometimes overlooked or undervalued in traditional ag.”

- “What is the saying? Man is from Venus, women from Mars? We have differing values, communication. I think we feel more open with women only.”

- “We think and process differently and having programs geared to us really helps comprehension.”

In order to offer a safe and open learning environment for participants, a conscious effort was made by team members to recruit only women farmers. Women farmers are a unique audience for Extension as their educational needs are very different from traditional male audiences. For example, women farmers have reported through focus groups and program evaluations that they feel uncomfortable asking questions during male-dominated workshops. The advisory committee and previous experiences working with this audience emphasized the need for programs especially designed for women in agriculture. Not only is the subject matter more appropriate for farm women, but these programs also help the participants feel at ease participating and asking questions. Also, women have different learning styles than men. As one participant stated, “What is the saying? Man is from Mars, women from Venus? We have differing values, communications. Different point of view. We think and process differently and having programs geared towards us really helps comprehension." Participants remarked how often they felt judged and dismissed in traditional male-dominated workshops. Their appreciation for having the opportunity to attend a workshop specifically for women farmers was evident through the evaluations. Future programs would benefit from surveying participants on any perceived learning environment challenges with male instructors compared to female instructors.

The ability to provide this type of in-depth instruction and resources is hindered by the limited resources committed to this target audience. Only so much of the ‘true cost’ of the program can be transferred onto the participants, especially if this program is to be offered to a more culturally and ethnically diverse audience. The small-scale nature of these value-added and direct marketing farm operations, as well as the financial challenges of beginning farmers, requires that educators find funding for this program through non-traditional means, like local business sponsorships. However, it will be necessary to find more significant, local, and long term funding for this and other beginning farmer educational programs to prepare the next generation of farmers.

Literature Cited

USDA. 20012. Census of Agriculture - 2012 Census Publications - Wisconsin. USDA - NASS - Census of Agriculture. Retrieved February 12, 2015, from http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2012/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_State_Level/Wisconsin/

USDA. 2007. Census of Agriculture - 2007 Census Publications - Wisconsin. USDA - NASS - Census of Agriculture. Retrieved February 12, 2015, from http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2007/Full_Report/Census_by_State/Wisconsin/index.asp.