Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 9, Issue 1 - June, 2016

Cooperative Extension and Neighbors: Adoption of Rain Gardens

- Rector, P., County Environmental Resource Mgmt Agent, Rutgers Cooperative Extension

Obropta, C.C., Extension Specialis in Water Resources, Rutgers Cooperative Extension

ABSTRACT

Adoption of a stormwater management practice, rain gardens, in an urban/suburban New Jersey neighborhood was investigated over a two phase educational and implementation program. A survey comparing responses of the project neighborhood and a control neighborhood found the project neighborhood knew more about the function of a rain garden (84.6%) compared to the control (40.0%). Seventy-two percent of residents who were interested in investigating a free rain garden in the 2nd phase (2014) responded that they were interested due to the 2010 campaign. Neighbors and the 2010 rain gardens played a large role in the interest and awareness of survey respondents to the 2015 survey (41%). This study provides preliminary results of how adoption plays out in environmental practice where the economic benefit to the individual is not a key selling factor.

Introduction

Introduction

In order to achieve reductions in non-point source pollution in our streams and rivers, especially in suburban/urban areas, changes in residential stormwater management are needed, typically on a voluntary basis. The introduction of rain gardens on a residential site to disconnect stormwater runoff is one such management practice, and the science exists to recommend this practice. The challenge becomes to have homeowners choose to adopt the practice.

Cooperative Extension, as the institution that brings the science to the community and helps the community make beneficial changes based on that knowledge, has a history of researching how individuals and communities change and adopt new behaviors. Although Ryan & Gross (1943) discussed early “acceptors” and how they provided the experience from which neighbors in an agricultural setting could gauge a new hybrid seed, the theory remains relevant as we introduce residential stormwater reduction practices. Ryan & Gross (1943) found that neighbors’ “experience within the community counted for more in terms of action.” Rogers (1963a) defined five stages in the adoption process; awareness, interest, evaluation, trial and adoption. While impersonal information sources (such as experts from Cooperative Extension) prove important in the awareness stage it is neighbors that are most important in the evaluation and adoption stages (Lionberger 1963b, Rogers 1963a).

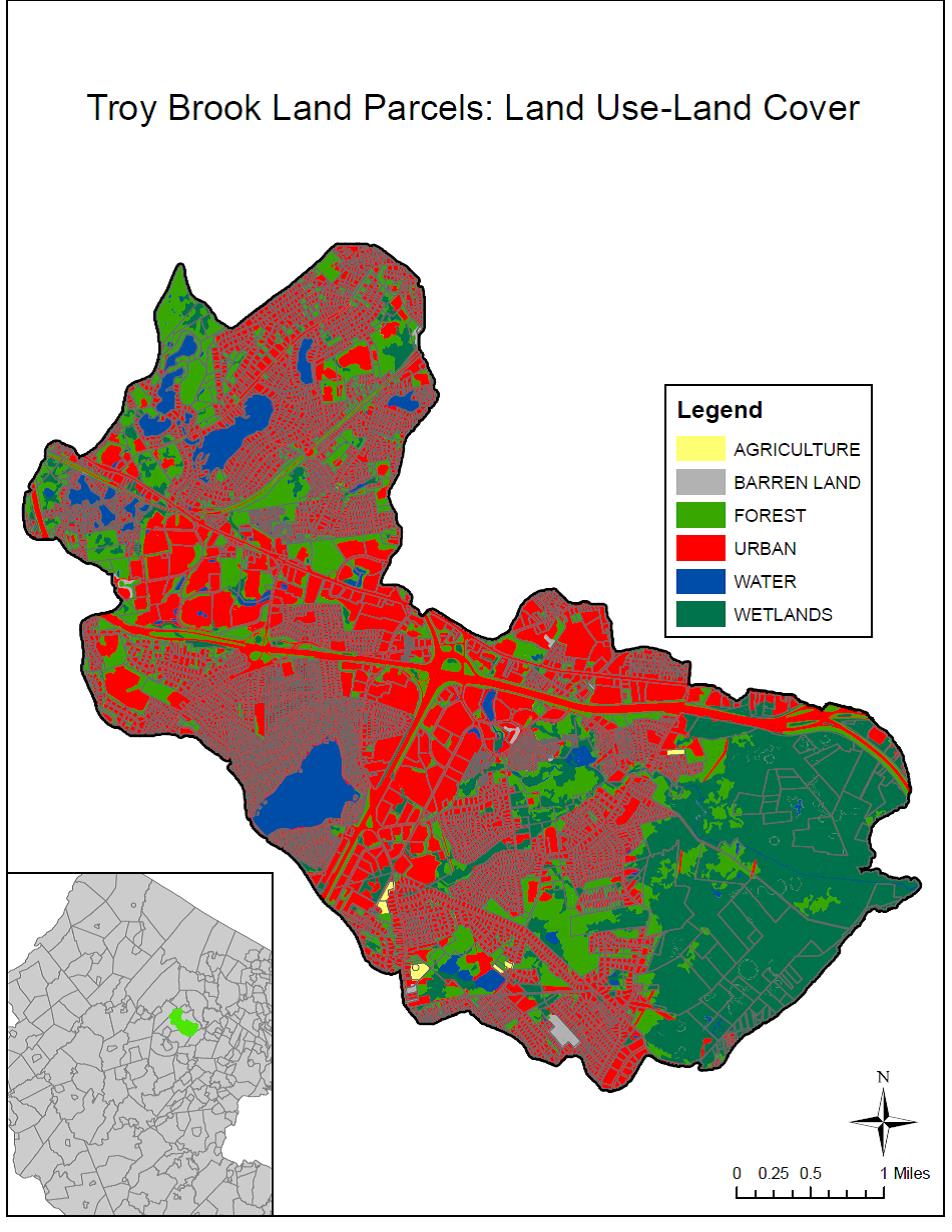

A Phosphorus Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for the Non-tidal Passaic River requires a 60% nonpoint source load reduction from urban areas to achieve water quality targets at critical locations within the Passaic River Watershed. The Troy Brook Watershed is a 16 square mile urban/suburban watershed, located in the north central portion of New Jersey (Fig. 1) that is ultimately a tributary to the Passaic River Basin. Rutgers University, Cooperative Extension (RCE) Water Resources Program (WRP) completed a Regional Stormwater Management Plan (RSWMP) for the Troy Brook Watershed. Based on this plan RCE received funding for Phase I and Phase II implementation in the Troy Brook watershed through the 319(h) Clean Water Act, administered in New Jersey by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP).

Although more than 200 demonstration rain gardens have been installed by Rutgers Cooperative Extension (RCE) WRP, the translation to residential rain gardens has been slow, and residential rain gardens remain uncommon. The RSWMP identified a neighborhood, the Hills of Troy (HOT), Township of Parsippany-Troy Hills, Morris County, N.J., as a high pollutant loading area. This neighborhood was selected as a pilot project for the implementation of a Cluster Rain Garden Program. As a component of the implementation project residential, clustered rain gardens in the HOT neighborhood were installed in 2010 (Phase I). The Phase I HOT Cluster Rain Garden educational campaign reached out to a focused residential neighborhood of 196 homes by canvassing door-to-door. The follow- up visits and the final installation within the neighborhood increased awareness of the Troy Brook and disconnection of impervious surfaces while reducing stormwater flow from five homes that are adjacent to or within close proximity to the Troy Brook. A second round of educational programming and rain garden installation was conducted in 2014 with a follow-up survey conducted in 2015 to determine some of the factors in the diffusion of the idea of rain gardens, and the willingness to adopt the practice. The factors related to adoption of residential stormwater BMPs have not been well examined (Brehm & Pasko, 2013). The cumulative project illustrates the interplay between technical models that identified a neighborhood that would provide the greatest pollutant removal and the boots on the ground, community approach that provides information leading to awareness, interest and adoption. The impacts of the 2010 rain gardens on neighbors were seen to assist in the investigation and adoption during the 2014 Cluster Rain Garden Campaign. While other studies provided survey-based data on existing environmental practices to provide baseline for future environmental changes (Blaine & Robbins 2012, Brehm & Pasko 2013), this study provides preliminary data on environmental adoption as it is occurring in the field.

Project Objectives

The HOT Cluster Rain Garden Program had four objectives:

- Conduct neighborhood-based education and demonstrations to increase the adoption of rain gardens.

- Demonstrate rain gardens built on a residential scale in a neighborhood setting.

- Determine factors which influence adoption within this neighborhood.

- Determine if the educational outreach increases rain garden knowledge in comparison to a similar, control neighborhood.

Figure 1. Troy Brook Watershed in Morris County, New Jersey

showing large portion of urban land use within the watershed.

Methods and Materials

Phase I (2010)

An introductory flyer was mailed to 196 residences in the HOT neighborhood and followed up with personal visits by the RCE Environmental County Agent, a Rutgers Environmental Steward or project staff. As part of the educational materials a “Porch Book” –with photographs and script, providing a 5-minute stormwater and rain garden tutorial to homeowners – was developed for use by all canvassers. The majority of residents (70%) received a personal face-to-face “Porch-Book” presentation. If a resident was not home a flyer was left at their residence and they were revisited at a later date; at a minimum all residents received an educational flyer. Eight interested homeowners were met for a two-hour follow-up visit.

Based on the resident’s willingness to proceed and site conditions, five residences had rain gardens installed. Educational signs were provided post-installation and displayed curbside to assure that the information continued to be promoted to neighbors (Fig. 2). All rain garden designs were completed by RCE and the gardens were installed at no cost to the homeowner.

Figure 2. 2010 rain garden installed with signage.

Phase II (2014)

Flyers (updated from Phase I) were mailed to 196 residences in the HOT neighborhood. In 2014 the President of the Neighborhood Association sent an email to all the residents in the community association encouraging homeowners to participate in the rain garden program. Interested homeowners (32) were met for a two-hour visit, followed with a design studio with the RCE WRP engineers and landscape architects. The design studios allowed homeowners to help design their rain garden and choose landscape plants. This is a higher level of homeowner engagement in the design process than in Phase I of this program. Thirteen rain gardens were installed at 11 residences in the spring/summer of 2014; an additional garden was planted in the spring of 2015.

Two distinct IRB-approved, incentivized surveys were administered by mail.

The first survey was mailed to 201 residents of a control neighborhood (Canterbury) also located in the Township of Parsippany-Troy Hills. The control neighborhood was chosen based on similar age of the development compared to the HOT development and comparative home value from the tax records. Brehm & Pasko (2013) conducted a survey that found household income was the 2nd best indicator of residential commitment of simple environmental practices such as proper disposal of pet waste. The rain garden survey questions related to knowledge of rain gardens (Table 1). The second survey was mailed to the 196 residents of the Hills of Troy. It included the same questions as the control survey but asked additional questions about the factors that increase awareness about rain gardens in the HOT neighborhood (Fig. 3), and changes in thought and behavior (Fig. 4).

RESULTS

Respondents from the HOT neighborhood had greater knowledge of what a rain garden was and the function of a rain garden than respondents from the control neighborhood (Table 1).

| Survey Question | HOT neighborhood respondents (%) who knew the answer | Control neighborhood respondents (%) who knew the answer |

|---|---|---|

| n=26 | n=35 | |

| Do you know what a rain garden is? | 88.5 | 40.0 |

| Do you know what the function of a rain garden is? | 84.6 | 40.0 |

For the question “Do you know anyone who has a rain garden?” fewer respondents from the control neighborhood (11.4% ) (n=35) knew someone who had a rain garden, while responses from the HOT neighborhood indicated that 80.8% of respondents knew someone who had a rain garden (n=26).

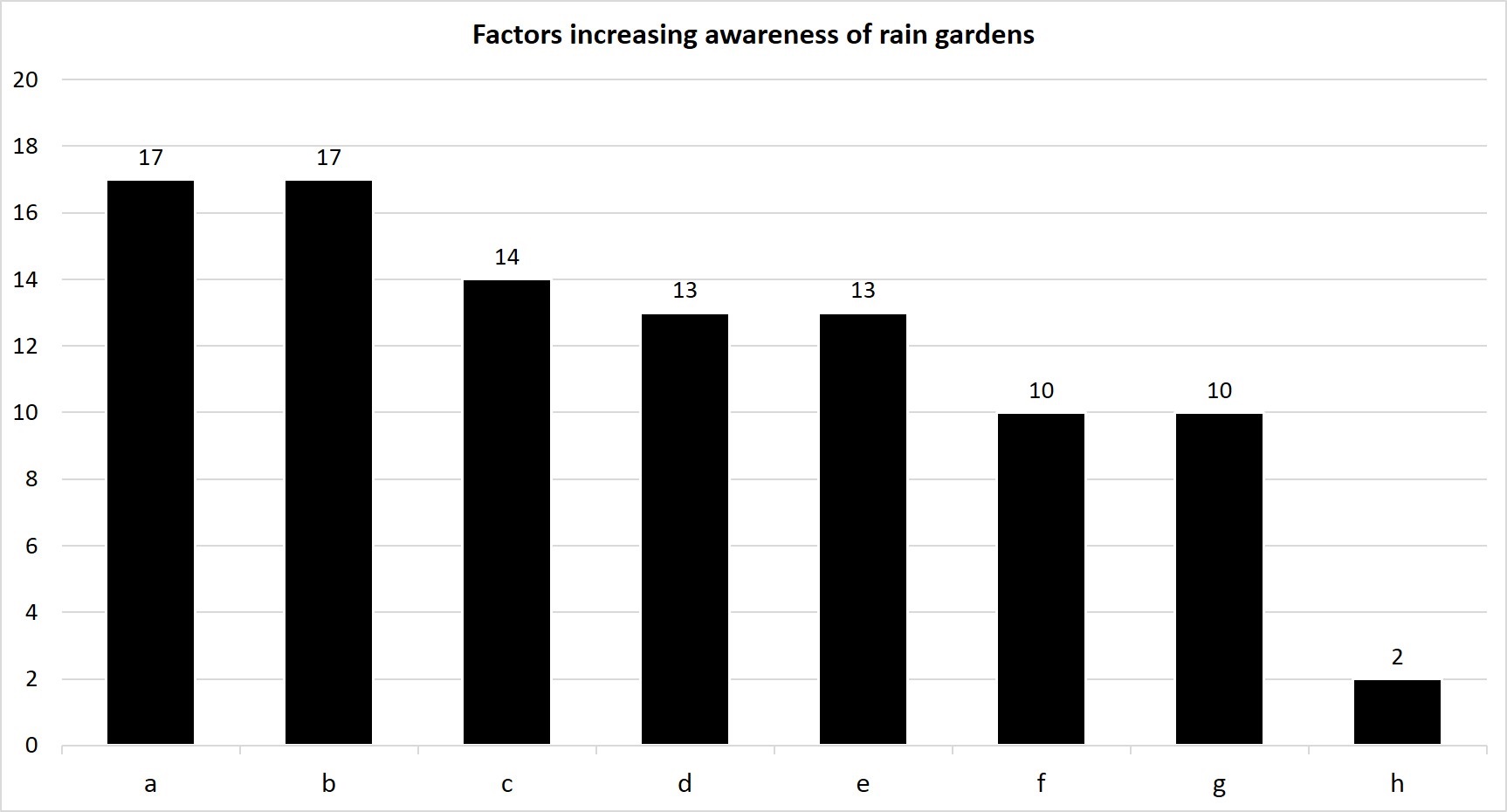

A survey question asked HOT respondents to choose factors (more than 1 answer allowed) that they felt increased their awareness about rain gardens (Fig. 3). Most (80%) chose 3 or more factors that increased their awareness of rain gardens. The survey question and available response choices were as follows:

I (please check all that apply)

a. was aware of the 2010 Cluster Rain Garden campaign

b. saw one or more of the rain gardens installed in 2010 in my neighborhood

c. saw the signage about the rain garden at one or more of the rain gardens

d. spoke to one or more of my neighbors about a rain garden

e. spoke to a Rutgers representative about a rain garden

f. received a flyer about the free rain garden campaign in 2014

g. received an email regarding the free rain garden campaign from the homeowner’s association

h. none of the above

Figure 3. Responses of residents of the HOT neighborhood to the factors of what increased their awareness of rain gardens. The letters follow the survey question responses above.

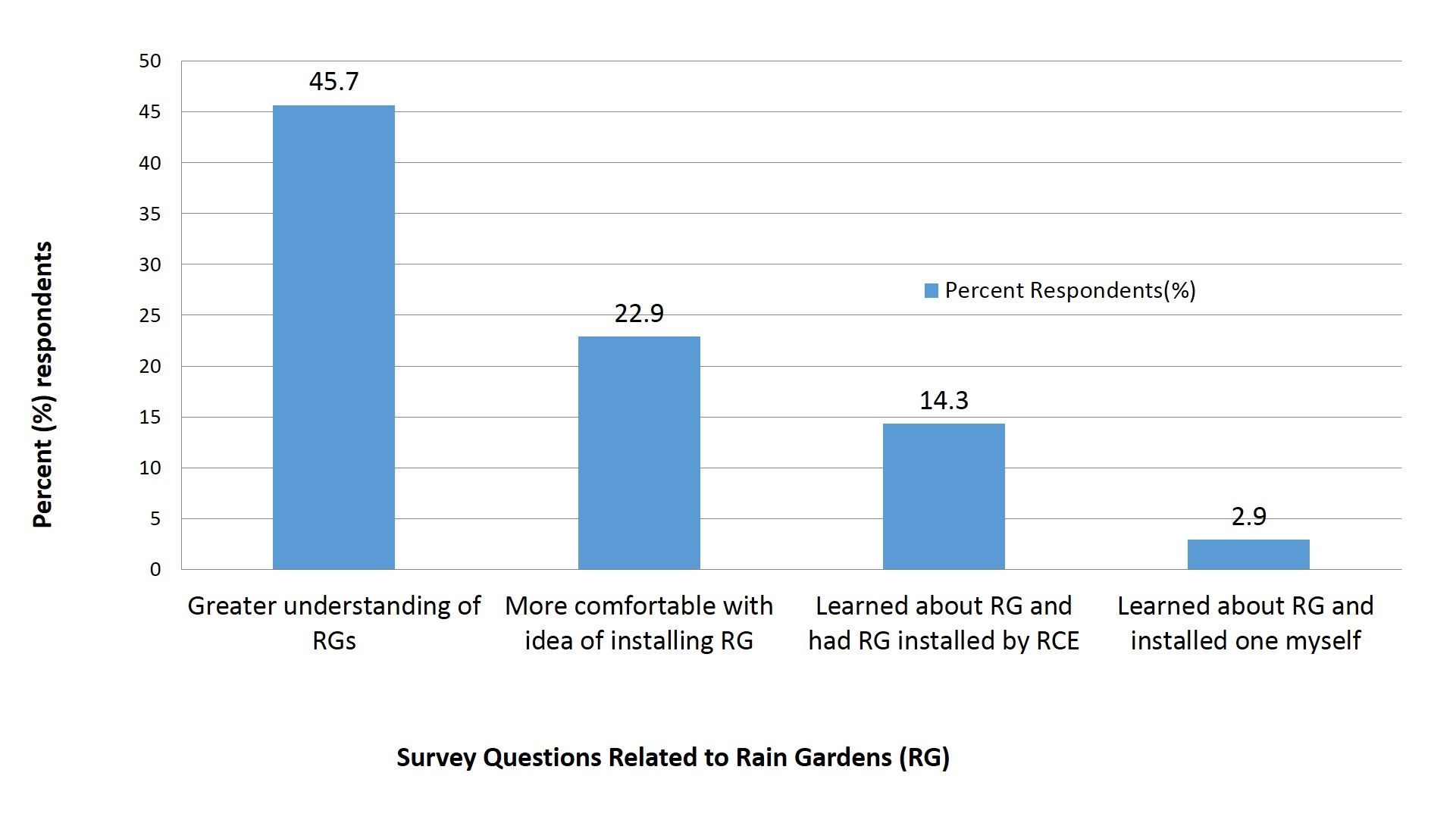

The responses to a survey question (below) regarding a change in thought and behavior show a predictable pattern (Fig. 4) with the greatest percent of respondents indicating an increase in understanding and in decreasing order the movement towards adoption; a willingness to investigate, willingness to install a free rain garden and a willingness to pay for and install their own rain garden (Fig. 4)..

As a result of the Rutgers Cooperative Extension Cluster Rain Garden campaign I (please check all that apply)

a. understand more about rain gardens

b. would be more comfortable with the idea of installing a rain garden

c. learned about rain gardens and I had one installed by Rutgers Cooperative Extension

d. learned about rain gardens and I installed one myself

e. none of the above

Figure 4. Respondent’s answers to questions regarding changes in thought or behavior as a result of the Cluster Rain Garden campaign.

Of those residents who were moving into the investigation phase of adoption during the 2010 initiative, eight residents were willing to investigate a free rain garden installation. During the 2014 initiative 32 residents were willing to investigate a free rain garden installation, a four-fold increase. The greatest number of respondents (72%) of these residents responded that they were interested due to the 2010 Campaign (more than one answer possible).

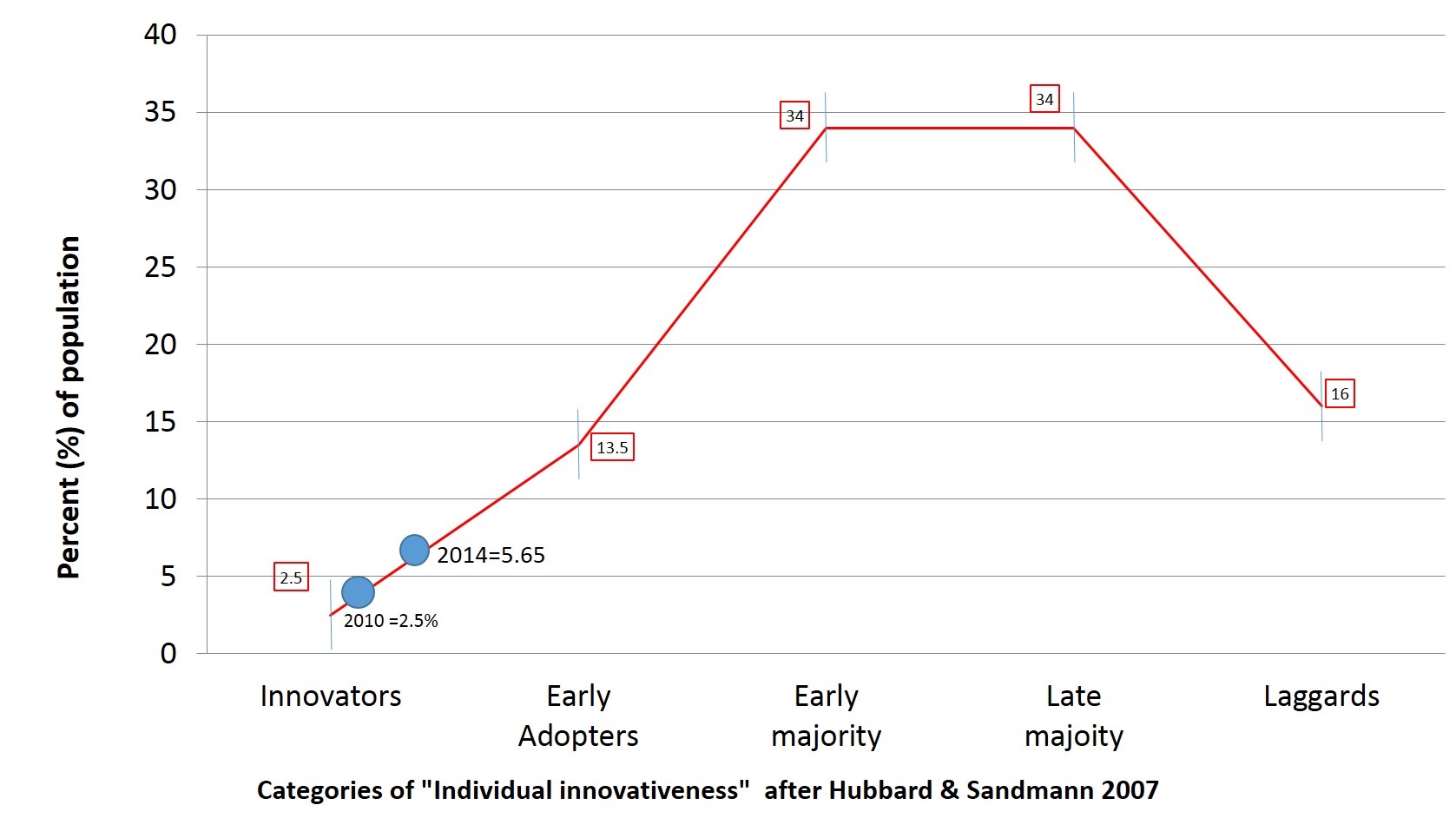

The 2010 Residential Cluster Rain Garden Campaign installed rain gardens at 2.5% of the residences in the HOT neighborhood. The 2014 Campaign installed rain gardens at 5.6% of the 196 residences, a few residences had more than one rain garden installed.

Figure 5. Percent of residences that have installed rain gardens in the Hills of Troy imposed on a classic bell curve of adoption with a breakout of individual innovativeness categories from Hubbard & Sandmann (2007). Innovators (2.5%), Early adopters (13.5%), Early Majority (34%), Late Majority (34%) and Laggards (16%) are shown on the graph.

Discussion

Bailey (1964) has identified characteristics that are helpful for diffusion and adoption of new practices:

- the relative advantage of the innovation

- the compatibility with the existing practice

- the divisibility of the innovation (ability to do a small sample project)

- the complexity of the innovation

- the communicability of the innovation

The HOT Cluster Rain Garden Program has many of these characteristics. The rain garden is an innovative means to manage stormwater runoff and address drainage problems that a property owner may be facing. One advantage for early adopters is that resources are available to support design and construction of rain gardens. These systems are compatible with existing landscaping features and can easily be incorporated into residential properties. The installation of demonstration rain gardens locally has been one of the keys to demonstrate this compatibility. Divisibility is linked to trialability, which both equate to reducing risk. People want to try innovative practices before adopting them, particularly if they are risky. Since a rain garden poses very little risk, divisibility/trialability is not as important. Once again, the demonstration rain gardens that are installed in the area help address these characteristics. Most homeowners would find nothing complex in the concepts of a rain garden, and the Porch Book is an example of the communicability of the concepts of rain gardens.

Phase I of the Cluster Rain Garden Program successfully achieved the objectives of installing demonstration rain gardens in the HOT neighborhood and conducting an educational campaign. Phase II reaped the benefits of this earlier campaign and we began to see signs of classic adoption theory. When attempting to encourage homeowners to adopt rain gardens, the installation of demonstration rain gardens locally and clustered has been one of the keys that have led to adoption.

Awareness and interest

Awareness and interest are the first two stages of adoption (Rogers 1963, Germain et al., 2014). The educational campaign was shown to be effective in this study for those residents who did and did not install a rain garden (Table 1). Respondents also answered this question with understanding being the first of the questions that can be considered adoption process questions (Fig. 4). Ryan & Gross (1943) found that the diffusion of knowledge came first and took several years, followed by adoption. Brehm & Pasko (2013) found in a survey conducted with 605 residents found that broad base knowledge was the greatest predictor of most beneficial landscape practices such as proper disposing of grass clippings, proper disposal of pet waste, and restoration of native plants.

Investigation/Evaluation

Despite RCE face-to-face communication with a majority of residents (70%) in the HOT neighborhood in 2010, only eight residents were willing to investigate a free rain garden on their property. The “experts” did not seem to be the spark that ignited the willingness to investigate installation of a rain garden. The outreach in 2014 did not initiate the program with face-to-face contact, but consisted of mailing an updated 2010 flyer to the 196 residences, yet 32 residents were willing to investigate a free rain garden.

During the Phase I campaign the president of the neighborhood association was skeptical of the ability of rain gardens to effectively manage stormwater runoff in the neighborhood. RCE engaged in considerable communication with this contact between 2010 and 2014. In 2014 he became an advocate for rain gardens and sent an email to all homeowners in the association to encourage participation in the Cluster Rain Garden Program. This increased RCE’s ability to provide personal connections. Ten percent of survey respondents credited their awareness of rain gardens to this factor (opinion leadership as per Rogers 1963b, or key communicator per Lionberger 1963b).

What else changed between 2010 and 2014? Based upon the survey, 54% of the HOT residents identified the demonstration rain gardens, the installation of these gardens, and their neighbor’s feeling about these gardens as the increased awareness of rain gardens.

• “saw one or more rain gardens” (17%)

• “saw rain garden signage” (14%)

• “was aware of the 2010 campaign” (13%)

• “spoke to one or more of my neighbors” (10%).

Ryan & Gross found that neighbors were given considerable weight to move from interest to acceptance/adoption of hybrid seed corn (Ryan & Gross 1943) and the influence of moving farmers to acceptance was neighbors (45.5%). In our study 54% of the interest and awareness of rain gardens (Fig. 3) can be related directly to neighbors and neighbor’s rain gardens, indicating that residents were paying attention to their neighbors.

The HOT neighborhood was selected for several reasons; it was identified through modeling and monitoring as an important area to disconnect impervious surfaces, it had an active neighborhood association, and reconnaissance of the area indicated it was a neighborhood where people of all ages were walking the streets of their neighborhood. The ability to turn a demonstration project into a stepping stone to adoption relies on several factors, but for residential practices one factor to increase effectiveness is a sense of community (Bailey 1963).

Trial stage/Adoption

The adoption of a stormwater management practice, rain gardens, in the Hills of Troy neighborhood appears to be following a similar trajectory (Fig. 5) as adoption of other practices in Extension literature (Lionberger 1963 a, b,). Fig. 4 shows a pattern of awareness (45.7%) followed by evaluation, where survey respondents say they are more comfortable with the idea of a rain garden (22.9%). Respondent’s answers then move on to action, with those who have had a free rain garden installed (14.3%), and finally (2.9%) installation of a rain garden themselves.

Innovators are typically identified as risk takers and Bierma et al., (1997) suggests these “risk-takers” or innovators would be the first 2% of adopters, while Surry (1997) indicates the risk-takers would consist of the first 2.5% of the select population. The first installers of residential rain gardens in the HOT neighborhood were 2.5% of the residences (Fig. 5).

The impact of neighbors on adoption can be seen in Figs. 6 and 7. The island effect in the 2014 rain garden (Fig. 7) was unnecessary, but was carried as an idea from the innovator from the 2010 Cluster Rain Garden Campaign. Blaine & Robbins (2012) found in a survey of 432 homeowners that 67% chose acceptance and their landscape “fitting in” with the look of the neighborhood as important to a suburban watershed. Although this attitude can be an impediment, it can become an asset as adoption begins to reach the majority.

Much of the Extension literature on adoption focuses on agricultural adoption. This study is one of the first to document adoption in the environmental resources realm. Why should this adoption of environmental practices be any different? Bierma et al. (1997) suggests that it is possible to sell “soap” or any other new technology at the point where the perceived need is great enough and the perceived cost is low enough. Extension-led farming practices are designed to a) save money either short term or long-term through protection of resources such as soil health or better farming methods or b) helping farmers comply with regulations (Ryan & Gross, 1943). Similarly, innovations that are intended to assist businesses understand a new technology that will assist in their work, save them money, and/or help them comply with regulations, also produce an economic benefit. In these instances often the “need” may be fairly apparent and the cost can be shown to be negative in the long-term. In either farming or business situation there is an expected economic benefit, short or long-term, albeit with a potential outlay of funds.

For environmental practices there is typically no direct economic benefit to the landowner, although occasionally rain gardens are designed to address drainage issues on residential sites. The benefit is to the waterbody and to the community downstream, and for the homeowner there is some cost for maintenance. Environmental adoption often requires looking past an individual economic benefit, and this might decrease the rate of adoption or increase the length of the timeline (vanEs & Pampei, 1975). The sale of “soap” becomes a harder sale at this point, hence the offering a “free” rain garden. We acknowledge the assistance of offering a free product, but show that even at free, adoption still follows a similar pathway, presumably because free simply levels the playing field. We include the initial installation and season as trial stage according to Rogers (1963) “the individual uses the innovation on a small scale in order to determine its utility in his own situation”. As the homeowner takes ownership, provides maintenance, replaces plants and mulch as needed, the garden becomes his/hers and they have “adopted” the rain garden.

Figure 6. 2010 Residential rain garden. The “island” was installed to provide a raised dry area for the disconnected lawn decoration.

Figure 7. Students building a rain garden located at 33 Homer Street. This 2014 rain garden was designed with an island in the middle of the rain garden at the homeowners request . The homeowner said he chose the design based on the design of a neighbor.

Conclusion

Early environmental water quality progress was made by regulations impacting point source pollution. Improvements in water quality now require solutions to non-point source pollution (people pollution) and this requires understanding how adoption of stormwater practices occurs at the residential community level. This study found that the traditional Cooperative Extension models of stages and roles of adoption worked well in the HOT neighborhood to understand adoption of rain gardens. Further research to continue to follow the adoption process in the HOT neighborhood is required.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Daniel Kluchinski for his assistance with development of the surveys used in this project.

References

Bailey, W.C. (1964). Result demonstrations and education. Journal of Extension {On-line}, 2(1) Available at:. http://www.joe.org/joe/1964spring/1964-1-a3.pdf

Bierma, T.J., Waterstraat, F.L., Kimmet,G. & Nowak, P. Jr. (1997). If it sells soap it can help sell innovations: A useful lesson from marketing. Journal of Extension {On-line}, 35(5) Article (5FEA2) Available at: http://www.joe.org/joe/1997october/a2.php

Blaine, T.W. & Robbins, P. (2012). Homeowner attitudes and practices towards residential landscapes management in Ohio, USA. Environmental Management. 50:257-271.

Brehm, J.M. & Pasko, D.K. (2013). Identifying key factors in homeowner’s adoption of water quality best management practices. Environmental Management. 50:257-271.

Germain, R.G., Ellis, B. & Stehman, S.V. (2014). Does landowner awareness and knowledge lead to sustainable forest management? A Vermont case study. Journal of Extension {On-Line}, 52(6) Article (6RIB3). Available at http://www.joe.org/joe/2014december/index.php

Hubbard, W.G. & Sandmann, L.R. (2007). Using diffusion of innovation concepts for improved program evaluation. Journal of Extension. 45(5): FEA1. Available at http://www.joe.org/joe/2007october/a1.php

Lionberger, R.F. (1963). Individual adoption behavior. Part I. Journal of Extension. 1(3): 157-166. Available at http://www.joe.org/joe/1963fall/1963-3-a6.pdf

Ram, S. (1987). A model of innovation resistance. In NA-Advances in Consumer Research Volume 14, (eds. M. Wallendorf and P. Anderson). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 208-212.

Rogers, E.M. (1963a). The adoption process. Part I. Journal of Extension {On-Line}, 1(1):16-22. Available at http://www.joe.org/joe/1963spring/index.php

Ryan, B. & Gross, N.C. (1943). The diffusion of hybrid seed corn in two Iowa communities. Rural Sociology. 8(3): 15-24.

vanEs, J.C. & Pampei, F.C. (1976). Environmental practices: New strategies needed. Journal of Extension {On-line} 14(3). Available at http://www.joe.org/joe/1976may/76-3-a2.pdf