Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 9, Issue 1 - June, 2016

Eat Well Volunteers Program Takes Feeding the Hungry to a New Level

- Peronto, M., Extension Professor, University of Maine Cooperative Extension, Hancock County

Yerxa, K., Associate Extension Professor, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

ABSTRACT

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension developed and piloted the Eat Well Volunteers program in Hancock County in 2014 and 2015. Using the Master Gardener Volunteers program as a model, we recruited and trained Eat Well Volunteers to conduct demonstrations at local food pantries, helping emergency food recipients learn ways to use fresh fruits and vegetables when preparing meals, and ways to preserve fresh produce for future use. Produce for this program was provided by Master Gardener Volunteers and local farmers. After two successful years piloting this initiative, we intend to continue its development, and urge other Extension colleagues to consider this program model as a way to equip food pantry clients with the supplies and knowledge needed to feed their families healthier foods.

Introduction

With one in seven of its residents relying on emergency food assistance, Maine is the most food insecure state in New England and the 18th most food insecure state in the country. (USDA ERS, 2014). Ironically, almost two-thirds of Maine adults (CDC 2009-2011) and more than a quarter of the state’s school-aged youth are overweight or obese. (Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. 2011,12).

Accessing healthy food is especially difficult for the working poor. Families experiencing low income often resort to purchasing inexpensive, calorie-rich, less nutritious foods at grocery stores. Fresh fruits and vegetables are perceived as too expensive. Also most food pantries, run by volunteers on shoestring budgets, cannot afford to provide a consistent supply of fresh fruits and vegetables to their clients. Federal subsidies make it possible for food pantries to stock their shelves with a selection of canned, dry, and processed foods at minimal cost, but to acquire fresh produce, many food pantries rely on intermittent donations of extra crops grown by local gardeners and farmers.

For the last ten years in Hancock County, Maine, Master Gardener Volunteers have made it a priority to grow and/or glean fresh fruits and vegetables specifically for food pantries. Food pantry managers are grateful to be able to provide these healthy food options to their clients. In recent years, however, as the amount of produce we have provided has increased, a new challenge has arisen: making free produce available does not always mean that it will be used. Some food pantries are having difficulty getting their clients to take all of the donated produce. Reasons given include recipients’ lack of knowledge about how to use fresh produce, and pantry volunteers often do not have the time or expertise to encourage fresh produce consumption. (Murphy, Yerxa and Savoie, 2014)

In response to this new challenge, UMaine Cooperative Extension created the Eat Well Volunteers (EWV) program. Modeled after the successful Master Gardener Volunteers program, Eat Well Volunteers receive research-based training in basic nutrition, food preparation, food safety and poverty awareness in exchange for conducting educational outreach at local food pantries.

The goal of the Eat Well Volunteers program is that food pantry clients will increase consumption of fresh produce and enhance food self-sufficiency skills as a result of interactive demonstrations conducted by trained volunteer educators.

In this paper, we take a close look at how the EWV program was implemented in its first two years in Hancock County, Maine, and the initial response it received.

Background

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension has convened and helped facilitate quarterly meetings of the Hancock County Food Security Network since 2004. This network consists of representatives from eleven food pantries, six community meal sites (soup kitchens) and five social service agencies concerned with hunger in the region. It provides a platform for these organizations to share resources, creatively solve problems, and organize advocacy efforts. Through these quarterly meetings, Cooperative Extension has developed relationships with and gained insights from food pantry managers. At these meetings we were made aware of the need for a consistent source of affordable, quality, fresh produce for food pantry clients, and subsequently we perceived a need for education in food pantries on how to cook and preserve this produce simply and safely.

Once Master Gardener Volunteers started growing and gleaning large quantities of produce for food pantries to distribute to their clients, food pantry feedback began to change. First, in response to our efforts to diversify people’s palates, pantry managers clearly said NO MORE UNUSUAL CROPS that people do not recognize, like arugula, red leafed lettuce, kale, or strange looking squash (patty pan); no-one will take them! Second, a percentage of the food pantry clients were walking by all of the fresh vegetables because they did not know how to cook with them, or they were intimidated by the idea of cooking from scratch.

Program Overview

The Food Pantries

In 2014 we piloted the EWV outreach program in two small, rural food pantries. Cooperative Extension had a friendly, supportive relationship with both of the food pantry managers, who were eager to give the program a try at their facility. In 2015 we expanded the program to include a third, larger food pantry.

Securing the Produce

For EWVs to conduct their outreach, they needed a supply of specific vegetables and fruits to give out while doing food preparation demonstrations with pantry clients. During the first year, we relied entirely on Master Gardener Volunteers to grow and/or glean the produce needed. In the second year, a Rural Health and Safety Grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) allowed us to supplement what Master Gardener Volunteers provided with crops grown by two local organic farmers. This helped us to expand our efforts to a third food pantry.

Recruiting Eat Well Volunteers

Our original hope was to recruit EWVs from those who had either worked in or received assistance from local food pantries. We approached food pantry managers, asking if they had potential candidates in mind, but soon discovered that the lives of people receiving food pantry assistance are too complicated to take on such a task. We then tapped into the Extension volunteer network (Master Gardeners, Homemakers, 4-H Leaders), issued public press releases, and reached out to individuals who we thought might be interested. As a result of these efforts we recruited four volunteers for the first year and two more in the second year.

Thus far our EWVs have come from higher income levels than the food pantry clientele. The poverty awareness component of the EWV training discussed below is therefore extremely important to program success.

Training the Eat Well Volunteers

UMaine Extension staff conducted a review of existing volunteer training resources within the national Extension network. The Master Food Volunteer training curriculum by Kansas State University Cooperative Extension provided material on basic nutrition and food safety for our introductory classes. We then developed additional classes which covered basic food preparation skills, introduced simple recipes using fresh produce, and addressed poverty awareness.

Our Eat Well Volunteers training consists of 30 hours of instruction divided into six weekly sessions as outlined in Table 1. In weeks 3 and 4, Food Preparation and Cooking Techniques with Fresh Produce includes washing, steaming, freezing, sautéing, stir frying, casseroles, roasting, crock pot cooking, and microwaving.

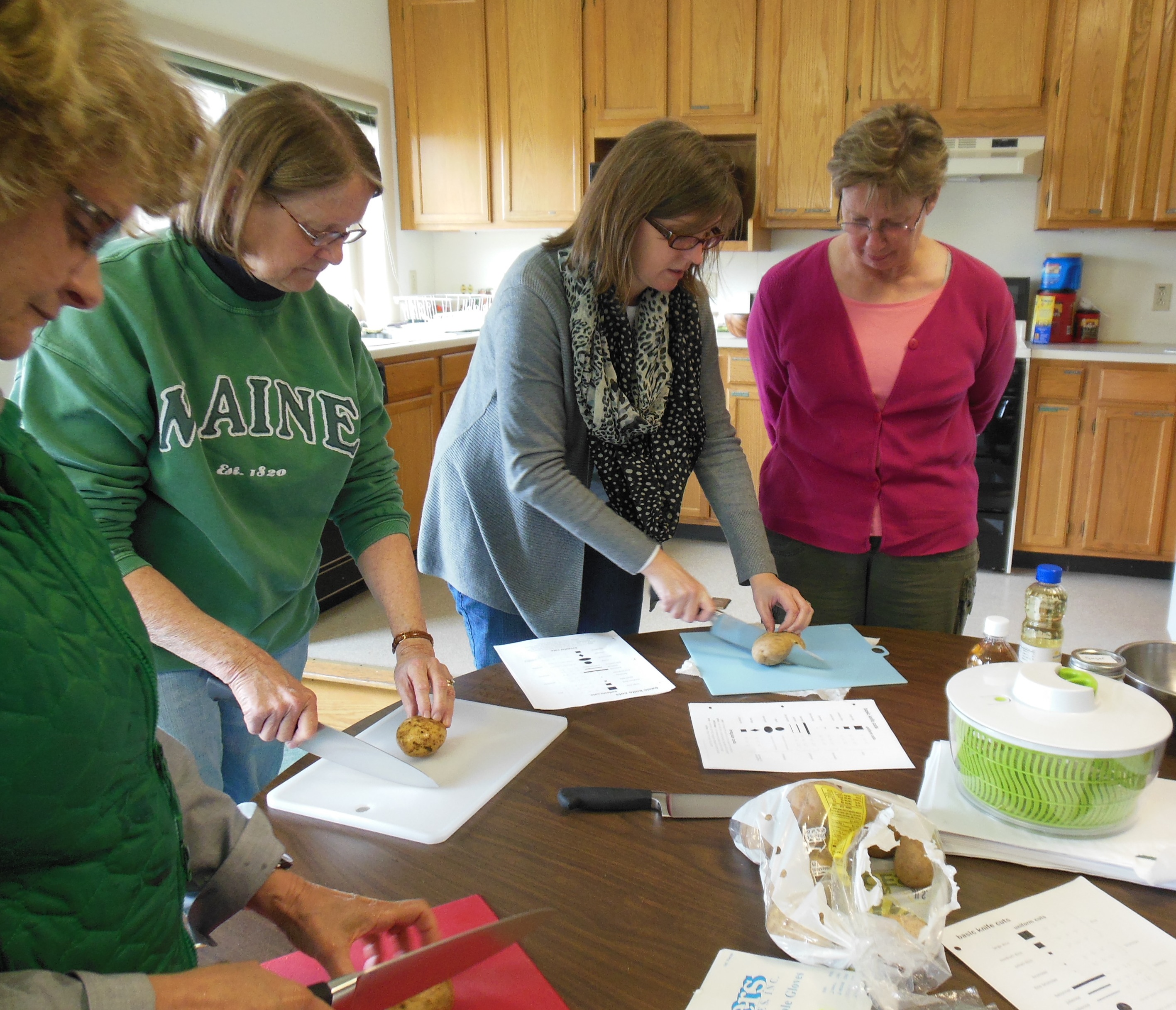

Figure 1. Eat Well Volunteers practice food preparation skills during training.

In order to help prepare volunteers for their outreach efforts, we devote a separate lesson (Class 5) to poverty awareness. To prepare ahead for this class, each EWV is asked to read at least one book from the following list:

- Closing the Food Gap: Resetting the Table in the Land of Plenty, by Mark Winne

- Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, by Barbara Ehrenreich

- The Glass Castle, by Jeannette Walls

- Without a Net: Middle Class and Homeless (with Kids) in America, by Michelle Kennedy

- Living Hungry in America, by J. Larry Brown and H. F. Pizer

- Hand to Mouth: Living in Bootstrap America, by Linda Tirado

On the day of this class, the students view the documentary on hunger in America, A Place at the Table. In-class discussion is centers on two questions:

- How did the books and documentary affect your knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about poverty and hunger?

- How can nutrition education make a difference for the population groups represented in the books and movie?

Class 5 ends with case studies based on real family profiles, illustrating the challenges and stresses faced by food pantry clients.

In the final class (class 6), Mock Food Demonstrations, the EWVs pretend that they are at a food pantry presenting to clients one of the demonstrations listed in Table 2. How do you interest a food pantry client in what you have to demonstrate, to listen for a few minutes on how to make kale chips, or how to freeze tomatoes?

At the end of the final class, EWVs are supplied with all of the equipment and utensils necessary to conduct each demonstration, including an electric skillet, crock pot, sauce pans, spatulas, cutting boards, knives, etc. These items were purchased with funds from the Rural Health and Safety Grant (NIFA) mentioned above. The fruits and vegetables for each class, spices, other ingredients, and educational handouts are prepared for the EWVs the day before each of their demonstrations at the food pantry.

| Class 1 |

|

| Class 2 |

|

|

Classes 3 and 4 |

|

| Class 5 |

Poverty Awareness

|

| Class 6 |

|

Table 1. Eat Well Volunteers Training Outline.

Eat Well Volunteer Outreach in Food Pantries

EWVs conducted their outreach from July through October 2014 and 2015, during the Maine growing season when the majority of produce is available. Table 2 describes each of the eight lessons that the EWVs delivered as the growing season progressed. Each lesson consisted of a food preparation skill, such as how to wash, steam, roast or freeze vegetables, and one or more simple nutritious recipes that highlighted cooking with a vegetable or fruit that was in season.

Working in pairs, he EWVs are set up at a table on the normal food distribution day for that pantry, and are present during the entire time that the pantry is open, typically three hours. Because of space limitations, EWVs can only interact with a few pantry clients at a time. This requires that they work quickly, delivering their lesson in five minutes or less.

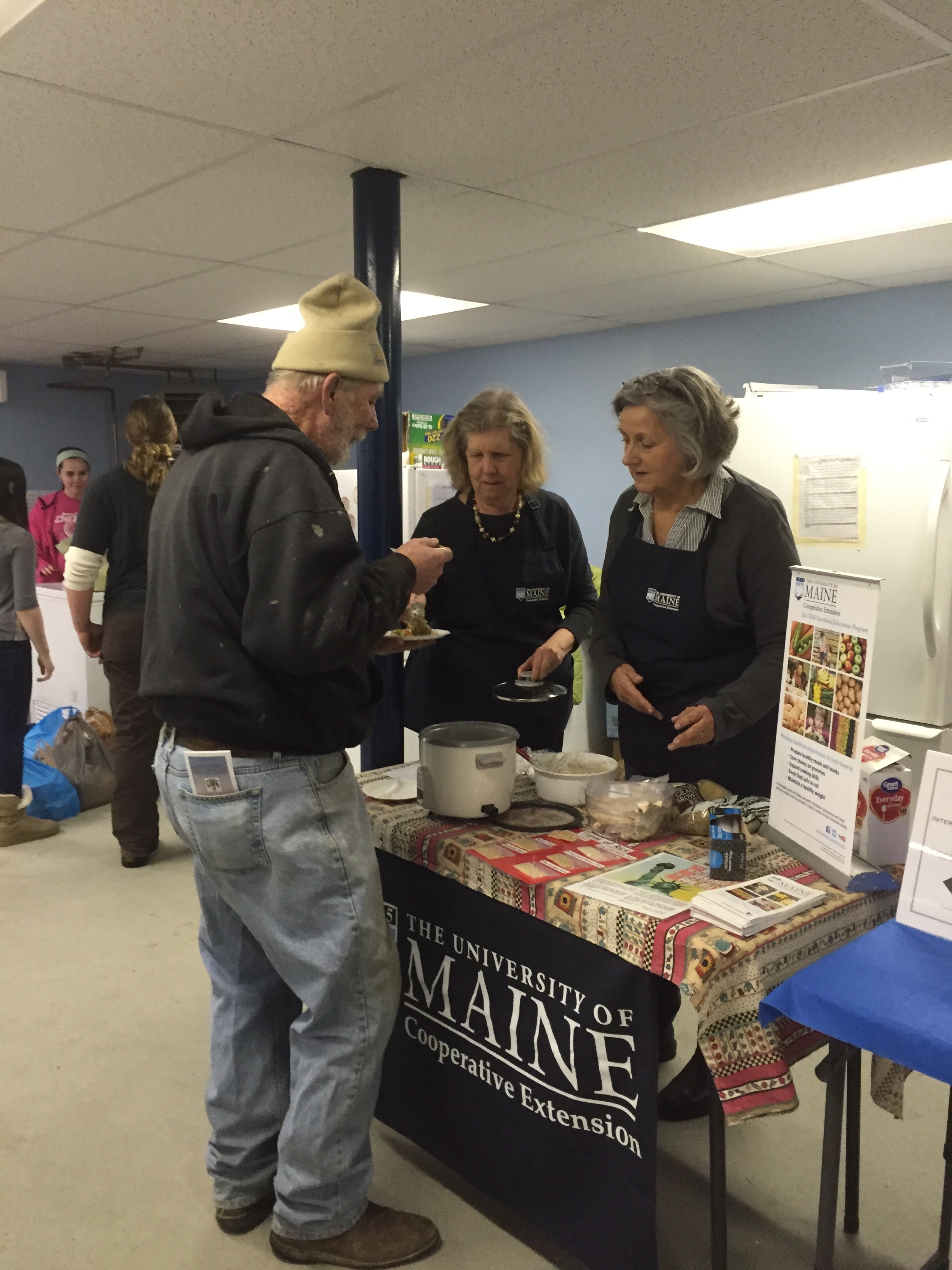

Figure 2. A food pantry client samples a recipe and talks with Eat Well Volunteers.

Client encounters at each participating pantry range from 15 to 20 clients per day. In 2014, the four Eat Well Volunteers had a total of 257 client encounters in two food pantries over four months. Many were repeat customers from month to month. In 2015, the six Eat Well Volunteers had 586 client encounters in three food pantries. Again, many were repeat customers.

| Month | Featured Produce | Food Preparation Skill Demonstrated | Taste Tests and Recipes Provided |

| Early July | Mixed greens | Washing |

Dill vinaigrette dressing Kale chips Kale and white bean soup |

|

Late July |

Green beans | Steaming |

Steamed vegetables with salt-free seasoning Green bean vinaigrette |

| Early August | Summer squash | Refrigerator stortage | Skillet saute or casserole |

|

Late August |

Tomatoes |

Freezing | Chile |

| Early September | Carrots | Roasting | Roasted root chips |

| Late September | Potatoes | Handling planned leftovers |

Potato pie Oven fries Potato crust |

|

Early October |

Winter squash | Crock pot cooking | Butternut squash soup |

|

Late October |

Apples | Microwaving |

Microwave stuffed "baked" apples Stovetop/crockpot applesauce |

Table 2. Eat Well Volunteer Outreach Lessons.

Program Assessment

Although this program is still quite young, we are beginning to get inspiring feedback from the Eat Well Volunteers, food pantry managers, and food pantry clients.

Program Feedback from EWVs: Extension staff conducted a personal interview with each of the six Eat Well Volunteers in February, 2016. Below are excerpts from these interviews.

Do you feel like you are making a difference in people’s lives?

EWV response #1: Most of the time yes, but it depends on the client. Sometimes people do not stop because they are in a hurry, or are embarrassed. Others are absolutely eager for the knowledge and for the produce itself. The program is good because it increases awareness. In a sense people are going shopping in a food pantry. We broaden what they have access to, and provide an opportunity for them to talk about nutrition. If we introduce 5 kids to fresh green beans who might otherwise never see them, that’s good! I believe in it!

EWV response #2: Yes, once we become familiar with the people and they become familiar with us. After being there on a regular basis, they look for us, to see what we have to sample, and have discussions with us about the food.

EWV response #3: We are trying to educate the client to eat healthier, more nutritious, fresh produce. A large part of it has been introducing them to vegetables they’ve never seen or tried before. They were surprised that it tasted so good.

Do you see any shifts in attitudes among food pantry clients around preparing meals using fresh produce?

EWV response # 1: For some, yes. Many would come back and say “Hey I tried this and it was really, really good.” The older people seemed to be the ones who would experiment more. I think that the younger people are quite dependent on prepared food, which breaks my heart.

EWV response #2: I do. But that kind of thing doesn't happen in a dramatic kind of way. People get used to having you there. They come and say “What do you have this week?” They want to sample it. Certainly they are open to it. For the most part they come back and say they’ve tried it at home.

Do you feel like you are building confidence in these end users?

EWV response #1: Yes. They are trying things. Tasting is a big step. They are taking the produce and recipes home, and getting their kids to try it. I don’t think it’s a one shot thing. You have to keep doing it and doing it with people. As your face gets more and more familiar, it is easier for the clients. People are starting to approach us and ask us cooking questions now!

EWV response #2: Absolutely. I miss seeing these people. I got to know them by name, Bertha, Gabriel. At first, I think everyone was really skeptical about us. By the end of the time, we wound up having a relationship. I am so looking forward to seeing them again. They’d ask, “When are you going to come back?” They were quite confident in what we were telling them. I miss them terribly.

Did you get what you had hoped for out of the training and volunteer experience?

EWV response #1: It exceeded my expectations. It made me have to think outside of my own little box. I went to the Culinary Institute of America, where you are surrounded with all the best food of the world, overstuffed.I love producing food, the feel of it, the taste of it, cutting it up; that to me is heaven.But what this did for me is make me see that I take so much for granted. Many of us have lost the concept of enough.Doing this, having to bring things down to basics, for me was a wonderful thing.I came out of it with more than I gave.I’d do it again in a heartbeat.We are probably all just one bad illness or one accident away from that food pantry.To walk around with an attitude that “these people won’t work…” NO.They are just like you and me; they just hit a bad patch.

EWV response #2: Yes! I like talking about food, sharing my knowledge about food, and I like teaching. I like the caring atmosphere in the food pantry. If someone can’t get to the food pantry, they will deliver. Or they will drive someone home.You don’t find that everywhere.When I was asked to go back to work part-time, I scheduled my work around my food pantry volunteer time, it means that much to me.I live alone, and I grow from sharing with other people.

EWV response #3: Absolutely.I have a different outlook now.There are so many different variables of why somebody doesn’t provide a nutritious meal; no time, no money, no background.When talking with somebody about what to do with vegetables, rather that just saying “this is the way to do it”, you have to talk with them about what works for them, what they want and need, and go from there. It is humbling when somebody comes in, a man in his 60s who is raising 2 children himself, trying to put together nutritious lunches for them.Or the gentleman who lost his wife last summer, and had never cooked, ever.It was all new for him.Those are the realities.

Program Feedback from Food Pantry Managers (FPMs): Extension staff conducted personal interviews with two of the three participating food pantry managers in February, 2016. (The third was not available). Below are excerpts from these interviews.

Do you think this program was successful, should it be continued, and why?

FPM response #1: It definitely was a very positive experience for us. I hope we can do it again next year. Education is the largest problem that any food pantry has. A lot of clients don’t know how to cook things that are available to them. The veggies don’t come with directions. Eat Well Volunteers teach them how to use and preserve the produce. Teaching them how to extend the life of nutritious produce is so much better than giving them a box of food.

FPM response #2: It has only enhanced what we are trying to do here. Any time you can get healthy, local produce into a food pantry, it helps us. Now we are teaching people how to feed themselves well. I love to see how the EWVs interact with the clients, and I definitely want them to come back!

What is the difference that this program has made in your efforts to feed the hungry?

FPM response #1: You’re teaching people the skill of preserving fresh fruits and vegetables in times of abundance for future use. In August, we get hundreds of pounds of tomatoes, 30 families can’t go through this amount in a day. You taught them how to core and freeze them for future use, and then they were all taken! One client came back today (February) and told me how he just finished the corn that he blanched last summer. Sustainability will feed them down the road so much better than me giving them a can of soup!

FPM response #2: It has expanded our vision. We are able to incorporate more healthy food in what we distribute. We have relied on canned veggies to such an extent, and now we are able through the volunteers to provide more nutritious foods. To someone on the outside it might seem insignificant, but to us, if a couple people will try something new, that’s a big step!

Program Feedback from Food Pantry Clients

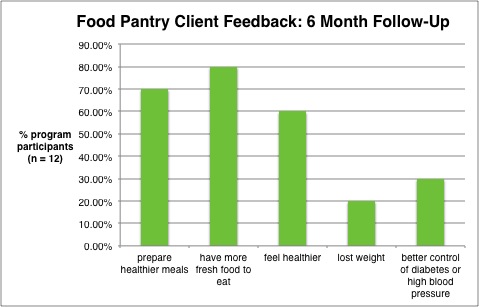

Forty food pantry clients were sent a follow-up survey in early 2015, six months after they had interacted with Eat Well Volunteers. The survey asked if interacting with Eat Well Volunteers had resulted in a) preparing healthier meals, b) having more fresh food to eat, c) feeling healthier, d)weight loss, or e)better control of diabetes or high blood pressure. Twelve clients returned the survey, for a 30% response rate. Results are shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Food Pantry Client 6 Month Follow-Up Survey Results.

Lessons Learned

EWVs count on having produce available to give away when conducting their lessons in food pantries. What if a crop fails? What if a crop harvest is delayed by weather? You need a backup plan for every week on the EWV outreach calendar, a plan that allows substitution of one lesson for another and takes into consideration the time involved for harvest and preparation of the produce.

Smooth management of behind-the-scene logistics is key to EWV program success. You need to be able to identify a support person to assemble all of the materials needed by the EWVs in their demonstrations, including the fresh fruits and vegetables. This person, perhaps another volunteer, must have the time and skills to coordinate with EWVs.

Prepare for initial discomfort among volunteers at the food pantry and low acceptance of the volunteers by pantry clients. It takes time for food pantry clientele to get used to new faces in this environment. Pair new volunteers with experienced volunteers. The first time a pair of volunteers goes to a pantry, an Extension Staff member should go with them to ease the transition. Emphasize potential pantry client discomfort in the EWV poverty awareness training.

If possible, engage food pantry clients by providing incentives. The NIFA Rural Health and Safety Grant mentioned above allowed us to purchase basic cooking tools such as steamers, strainers, potholders, freezer bags, and measuring utensils, items that make it easier for clients to apply what they have learned. These items were used as incentives for participation.

The hands-on component of EWV outreach is limited due to lack of time and space at most pantries. For example, we found that there was no space or time to have clients mix their own spices for a recipe. Instead, EWVs provided pre-mixed spice packets for vinaigrettes, soups and chili recipes in small plastic bags. Involving clients in the preparation of recipes slowed things down and created foot-traffic-flow problems inside the food pantry, reducing the number of clients we could reach.

Determining long-term program impact on food pantry clients is difficult, at best. Clients are often unwilling to share contact information, making it difficult to follow up. Some food pantry clients are transient. Some do not have phones. Literacy is an issue with some clients. Getting anyone to fill out a survey is difficult, but someone who is trying to meet basic survival needs has no reason to make it a priority.

References

USDA Economic Research Service: Food Security in the US, (2014). Key Statistics and Graphics. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx#map

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), (2009-2011). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. (2011,12). National Survey of Children's Health. Available at: http://childhealthdata.org/browse/snapshots/obesity-2007?geo=1.

Murphy B, Yerxa K, Savoie K., (2014). Maine Harvest for Hunger and Eat Well Volunteers – Combining the Passions of Volunteers to Address Food Insecurity in Maine. Professional presentation and paper submission at the Century Beyond the Campus: Past, Present, and Future of Extension: A Research Symposium to Mark the 100th Anniversary of the Smith-Lever Act. Morgantown, West Virginia. September 24 - 25, 2014. Retrieved from http://smithlever.wvu.edu/papers.

Peronto, M.L., (2015). Master Gardeners and Eat Well Volunteers Work Together to Address Hunger and Poor Nutrition Among Mainers who Rely on Emergency Food Assistance. Presentation. National Association of County Agricultural Agents Proceedings: 100th Annual Meeting and Professional Improvement Conference, Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Retrieved from http://www.nacaa.com/ampic/2015/2015%20Proceedings%20web.pdf

Peronto, M., Yerxa, K., Spurling, D., (2015). Pilot Volunteer Program Increases Access to and Use of Fresh Produce by Food Pantry Clients in Hancock County Maine. National Association of County Agricultural Agents Proceedings: 100th Annual Meeting and Professional Improvement Conference, Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Retrieved from http://www.nacaa.com/ampic/2015/2015%20Proceedings%20web.pdf

Feeding America: Food Insecurity in Maine (2013). Retrieved from http://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2013/overall/maine

Good Shepherd Food Bank: Hunger in Maine (2016). Retrieved from http://www.gsfb.org/hunger/

Kansas State University Extension Master Food Volunteer Program Handbook. Retrieved from https://www.ksre.k-state.edu/mfv/resources/handbook.html