Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 10, Issue 2 - December, 2017

Annie’s Project Farm and Ranch Business Management Course for Women Created Positive Impacts in 14 States

- Schultz, M. M., Women In Ag Program Manager, Iowa State University Extension And Outreach

Hyde, C. J. , Graduate Student , Iowa State University

de la Mora, A., Ph.D. , Research Scientist , Iowa State University

Eggers, T. R. , Field Agricultural Economist , Iowa State University Extension and Outreach

Leibold, K. L. , Farm Management Specialist , Iowa State University Extension and Outreach

ABSTRACT

As leaders, family communicators, and visionaries of tomorrow’s rural landscapes, women are influential decision makers. They are stepping up to challenging and changing roles in agriculture. This creates a critical need for education directed specifically to this gender. Annie’s Project educators created positive impacts for women in fourteen states from 2013 to 2015. More than 677 women from 76 courses responded to a national survey. Annie’s Project courses were successful in extending knowledge in the five agricultural risk areas of finance, human resources, legal, marketing and production. Results indicate a statistically significant difference in the overall mean knowledge gains from pre-course assessment to post-course assessment with p>.01 in all content areas combined. Overall survey respondents who agreed or strongly agreed the best education practices were implemented were more likely to make gains in knowledge than respondents who disagreed or strongly disagreed the best education practices were implemented. Results showed participants took important actions towards managing all five agricultural risks. When farm and ranch women are empowered, they can contribute to a more sustainable agriculture by improving economic resiliency, conserving natural resources, and taking on influential roles in their families and communities. Extension educators have an important role in risk management education for women.

Introduction

As leaders, family communicators, and visionaries of tomorrow’s rural landscapes, women are influential decision makers. They have significant employment, management and ownership on America’s family farms and ranches. Nearly one in three farmers is a woman. The USDA-NASS 2012 Census of Agriculture counted 969,672 women farm operators (31 percent of all farm operators in the United States; USDA NASS, 2012). The 2012 Study of Farmland Ownership and Tenure in Iowa (Duffy and Johanns, 2014) shows women own 47 percent of all Iowa farmland. Yet, USDA identifies women farmers as an underserved audience.

More women are starting new agricultural businesses, becoming the next generation of family farmers, and taking on management responsibilities in rural areas. These women are stepping up to challenging and changing roles in agriculture while enhancing the profitability of family farms and ranches and improving national food security. This creates a critical need for education directed specifically to this gender to help them manage business risks, enhance the profitability of their family farms, and plan for generational succession.

Through local small-group Annie’s Project courses, educators offer opportunities for women to learn from one another, engage in hands-on activities, and create support networks. Course participants who completed surveys in fourteen states increased their knowledge and took important actions towards managing agricultural risks. The survey results demonstrate the important role extension educators have in risk management education for women.

Education for Women Farmers

Agriculture education programs are designed to meet the needs of farmers, but have been slow to address the needs, experiences, and expertise of women in agriculture (Albright, 2006). Additionally, many women feel as though they are not respected or viewed as farmers, and in many community settings women feel uncomfortable and avoid asking questions or engaging in conversations (Charatsari et al., 2013).

Farm women and their contributions are becoming more visible in agriculture (Sachs et al., 2016). In 2012, women were reported as 13.6 percent of all principal farm operators and 67.5 percent of all secondary farm operators (USDA NASS, 2012). Principle farm operators are responsible for the day-to-day decision-making for the business. The primary roles of the secondary women operators include maintaining the financial well-being of the farm, taking care of the home, or working off the farm to contribute extra income or health benefits (Fenton et al., 2010). Some women also work as secondary operators of owned farmland that is leased to other primary operators (Duffy & Johanns, 2014). Eighty-three percent of the women principal operators were full owners of their farmland and another 11 percent were part-owners of their farmland (USDA NASS, 2012.)

Women have been involved in the development of their rural and farming communities for generations, but there is still a lack of understanding of the challenges women face (Albright, 2006). Women are cautious about entering agriculture education spaces, which have historically neglected to take into consideration the barriers women farmers face such as juggling off-farm work in addition to their work for the farm (Charatsari et al., 2013), and have rarely been included as a source of knowledge (Trauger et al., 2008).

Women are taking on more leadership roles and forming new programs and organizations (Albright, 2006). Educational programs and farmer-to-farmer peer networks have arisen to pass on knowledge specific to women farmers and ranchers and address the unique needs and challenges of being a woman farmer. This provides legitimacy and recognition for women in agriculture. The diffusion of knowledge is key for women to succeed and lead in their roles as farmers. The use of women’s knowledge and shared experiences in the development of the programs is important to other women farmers (Charatsari et al., 2013).

Annie’s Project – Education for Farm Women non-profit organization differs from other women’s agriculture networks and educational programs because of its direct emphasis on including the voices of women farmers and ranchers to establish the program agendas, to promote gender equality in agriculture, and to gain recognition of their course participants as producers and operators. Women often feel like they are not taken seriously or their input is not valued during agriculture education programs (Charatsari et al., 2013). Annie’s Project makes efforts to ensure women are comfortable during their courses and are able to learn from each other as well as local professionals.

In general, the new women’s networks offer knowledge and skill building opportunities and a network of women with ideas that have been tested on their own farms. They also offer social support that can alleviate isolation, legitimatize women’s identities as farmers, and increase their capacity as farmers; ultimately enhancing the success of farm businesses (Sachs et al., 2016).

Annie’s Project – Education for Farm Women

Annie’s Project – Education for Farm Women is a non-profit organization whose mission is to empower farm and ranch women to be better partners through networks and by managing and organizing critical information. Educators in more than 30 states have partnered with the organization to offer branded Annie’s Project courses to more than 12,000 farm and ranch women (Figure 1).

Ruth Hambleton, who was an Extension Farm Business and Marketing Specialist with the University of Illinois at the time, developed Annie’s Project in 2002. The USDA NIFA - North Central Extension Risk Management Education Center led by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln provided financial support for developing the program. For more information on Annie’s Project, please visit www.anniesproject.org.

Figure 1. Annie’s Project national branding logo.

Annie’s Project courses are designed for women interested in starting, working in, or managing farm or ranch businesses. Women become more knowledgeable about agricultural businesses through a series of six weekly classes (18-hours total). Specific objectives are to increase risk management knowledge and empower women to implement new practices in the five agricultural risk areas of financial, legal, human resources, marketing, and production. Annie’s Project creates a comfortable and supportive learning environment focused on the best farm business management practices. This enables women to be even stronger business partners in their farming or ranching operation.

Educators become certified Annie’s Project facilitators through professional development programs organized by the Annie’s Project – Education for Farm Women organization (Schultz et al., 2016). These educators develop Annie’s Project courses that offer local, small group, multi-session, face-to-face educational opportunities aligned with women’s unique learning preferences. Several other best education practices are summarized in the key principles and core values below.

Annie’s Project Key Principles:

· Teach all five areas of agricultural risk; financial, human resource, legal, marketing and production.

· Invite local women professionals to serve as guest instructors where possible.

· Allocate half of class time to discussion and hands-on activities.

· Provide unbiased, research-based information.

· Create a learning environment where mentoring is spontaneous.

Annie’s Project Core Values:

· Safe harbor where all questions or situations are welcome.

· Connection and networking among farm women and professionals.

· Discovery as skills practice leads to moments when new concepts make sense.

· Shared experiences as participants contribute their own subject matter expertise.

The Annie’s Project curricula includes information and skills training to help women improve decision making around specific farm and ranch management topics. This helps women understand the whole-farm or overall management goals of the farm business. The course covers all five areas of agricultural risk management: financial, human resource, legal, production and marketing. All five areas are critical for successful business management on farms (Hiens et al., 2010). Within those five areas, Annie’s Project educators cover thirteen essential topics as follows.

Annie’s Project Essential Risk Management Topics:

1. Development of Financial Documents (Financial)

2. Interpretation of Financial Documents (Financial)

3. Enterprise Analysis (Financial)

4. Women and Money (Financial)

5. Communication (Human Resource)

6. Insurance for Farm Families (Human Resource)

7. Property Ownership and Estate Planning (Legal)

8. Grain, Livestock or Direct Marketing (Marketing)

9. Farm Leasing (Financial and Production)

10. Farm Service Agency (Production)

11. Crop Insurance (Production)

12. Natural Resource Conservation Service (Production)

13. Web Soil Survey (Production)

Methods

The Iowa State University Research Institute for Studies in Education (RISE) and Annie’s Project educators worked together to design survey instruments that can be administered online via Qualtrics or on paper. The Annie’s Project data was collected directly by RISE, who served as an unbiased third-party. Surveys contained knowledge and practice questions in the five agricultural risk areas, plus demographic and open-ended questions. A paired t-test was used to analyze knowledge gains from pre- to post-course surveys and correlational analysis was used to examine the relationship between participant perceptions of best education practices used in the course and their overall gain in knowledge. In addition, the Annie’s Project educators collected anecdotal stories and shared videos of past participants talking about how the courses benefited the women participants and their family farms and ranches.

Survey Participants

Fourteen states cooperated to use the same standard evaluation instruments to collect data from Annie’s Project participants in 76 courses between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2015 (Figure 2). The states were Alabama, Arizona, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, and South Dakota.

Figure 2. Map of states partnering in national program evaluation.

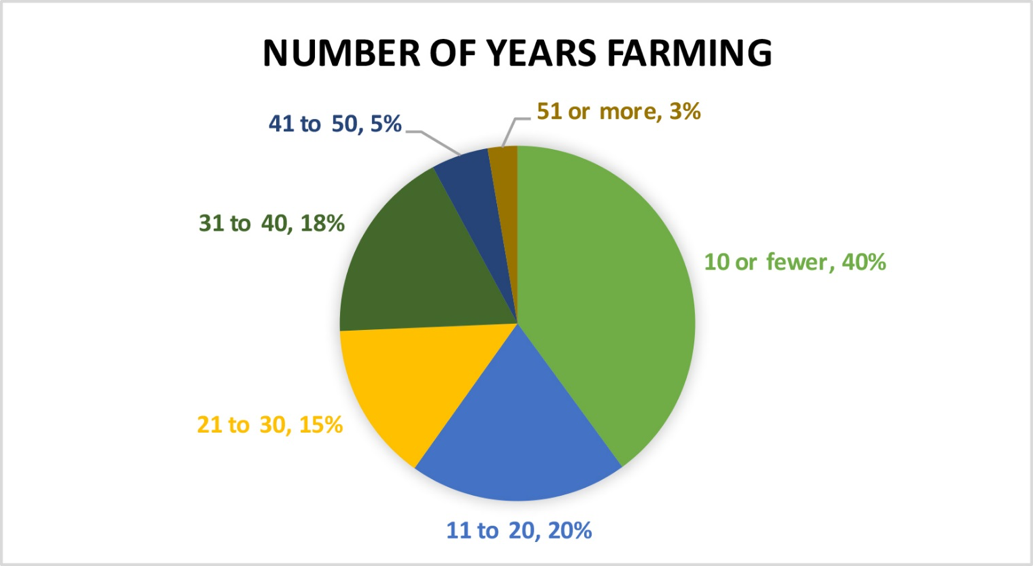

A total of 1,177 participants responded to pre-course surveys and a total of 916 participants responded to post-course surveys. Anonymous identification codes allowed RISE to match pre- and post-course survey results. Of all survey participants, a total of 677 completed both pre- and post-course surveys and are included in the study. Participants ranged in age from 25 to 75 or more years of age. Slightly less than half (44.3%) of the participants were under the age of 45, and about half (48.9%) were between 45-64. The remaining women were 65 years of age or older. One-third (33.5%) of the survey respondents were beginning farm and ranch women who have operated a farm or ranch business ten or fewer years (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Number of years farming.

Instruments and Procedures

Pre- and post-course surveys were designed to assess the effectiveness of the Annie’s Project course. Specifically, surveys assessed participant knowledge and practice changes in the five areas of risk management. Surveys requested feedback from participants on the usefulness of the course and whether selected best education practices met their needs. Pre- and post-course surveys were administered to participants in 76 Annie’s Project courses on the first and sixth (last) session of each course respectively. The number of participants in each course ranged from six to 30 participants.

Pre- and Post-course surveys consisted of a total of 27 knowledge questions on the five business risk management topics covered in Annie’s Project: financial (e.g., calculating costs of production, seven questions), human resources (e.g., insurance needs, six questions), legal (e.g., estate plans, three questions), marketing (e.g., price discovery, four questions), and production (e.g., how crop insurance works, seven questions). Participants were asked to indicate the extent of their knowledge about each statement on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("I know little or nothing about this") to 4 ("I am completely familiar with this").

Participants were also asked about current practices in each of the five risk management areas described above. Participants were asked to indicate their current practices on a 3-point scale; “Yes, I already do/have done this,” “I don’t now, but I intend to,” and “No, I don’t now and I don’t plan to.”

To determine whether Annie’s Project educators upheld the key principles and core values, survey questions assessed the perceptions of the participants. Post-course survey questions asked participants to indicate the extent to which they agreed with each statement on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) on seven statements (e.g., “the course provided a safe environment for learning,” and “I felt encouraged to learn from other participants…”).

Results

Analysis of the national survey results showed the courses were successful in significantly improving the knowledge of women in all five risk management areas. In addition, women implemented risk management practices in all risk areas during the six-session Annie’s Project course. More than 95% of survey respondents indicated educators encouraged them to learn from both classmates and speakers, and educators provided a safe and nurturing learning environment.

Survey respondents selected legal/estate topics as the most valuable topics more often than other topics. Through open-ended survey questions, respondents stated financial management goals for applying what they learned more often than other goals (Figure 4). Respondents stated human resource/communication topics as ‘unexpected learning’ more often than other topics, and stated they wanted more on marketing and production topics more often than other topics.

Figure 4. Goals for applying learning.

Knowledge Gains

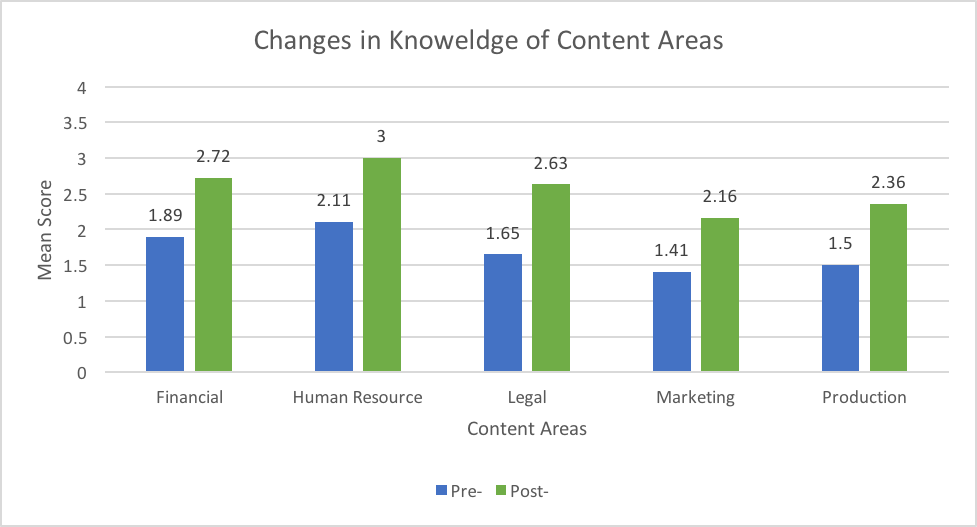

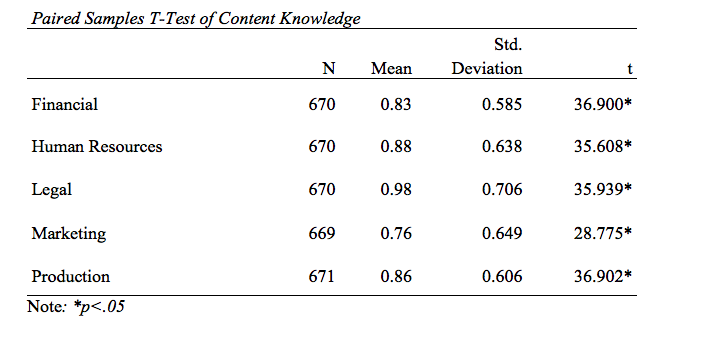

To assess overall knowledge gains between the pre- and post-course surveys, total scores were computed by summing together participant scores for each question to create constructs for every risk area: financial, human resource, legal, marketing, and production. The results indicate participants gained knowledge in all five risk management topics: financial, human resource, legal, marketing, and production. Respondents made the greatest gains in Legal and Human Resource content areas (Figure 5 and Table 1).

Figure 5. Changes in knowledge of content areas.

Table 1. Paired samples of t-test of content knowledge.

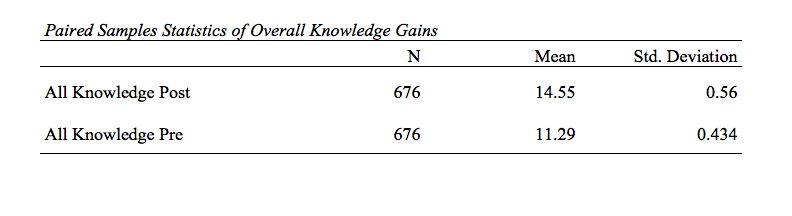

Additionally, results show a statistically significant difference in the overall mean knowedge gains from pre-course assessment to post-course surveys in all content areas combined (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Paired samples statistics of overall knowledge gains.

Table 3. Paired samples of t-test of overall knowledge gains.

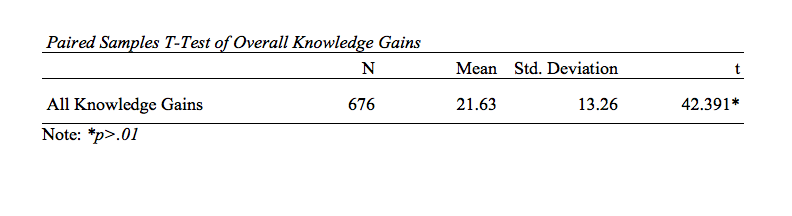

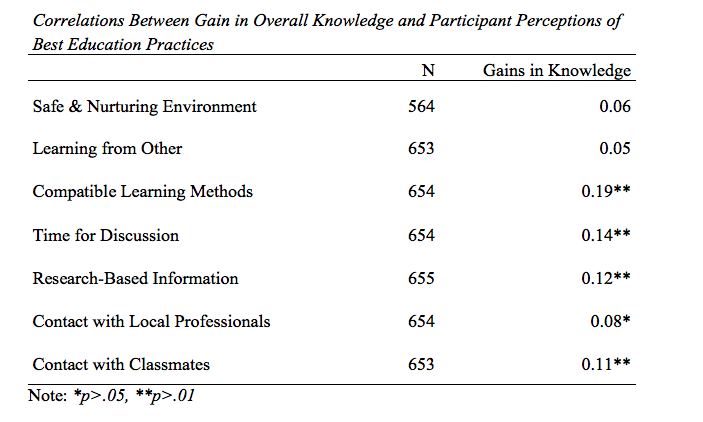

The matched data set of the overall content knowledge gains was further analyzed using a correlational analysis to determine the relationship between the perceptions of best education practices and overall knowledge gains. The gains in participant knowledge for each content area was positively related to the participant’s level of agreement to the use of Annie’s Project best education practices (Table 4). Statistically significant relationships exist between five of the six educational practices: compatible learning methods, time for discussion, research-based information, contact with local professionals, and contact with classmates. Overall survey respondents who agreed or strongly agreed the best education practices were implemented were more likely to make gains in knowledge than respondents who disagreed or strongly disagreed the best education practices were implemented.

Table 4. Correlations between gain in overall knowledge and participant perceptions of best educational practices.

Behaviors Changed

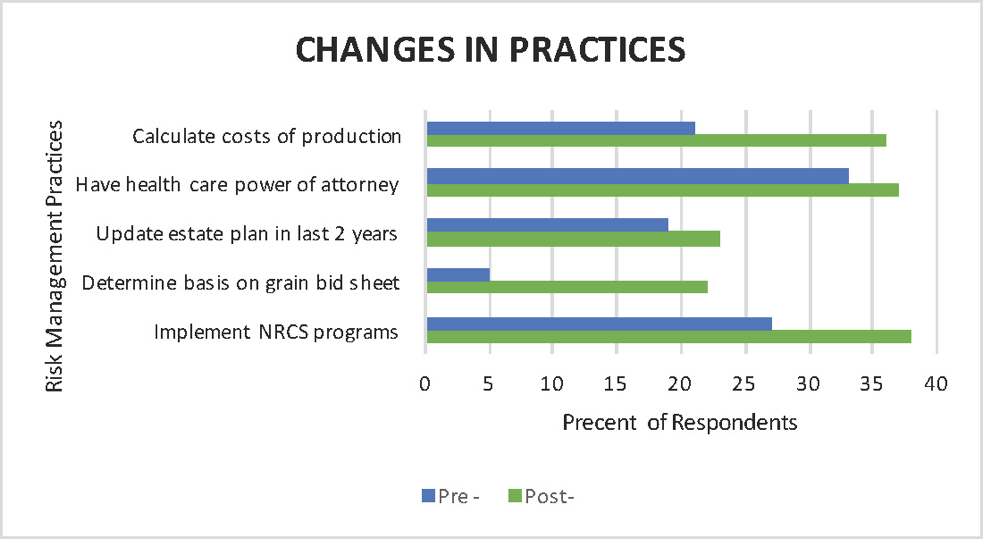

Comparison of pre- and post-test results indicate that women participating in the course changed their behavior in each of the five risk management areas; financial, human resources, legal, marketing and production. When looking at only the answer of “Yes, I already do/have this,” the percent of responses increases during the 18-hour Annie’s Project course. The women completed risk management tasks in each risk management area as demonstrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Changes in practices from pre- to post-course surveys.

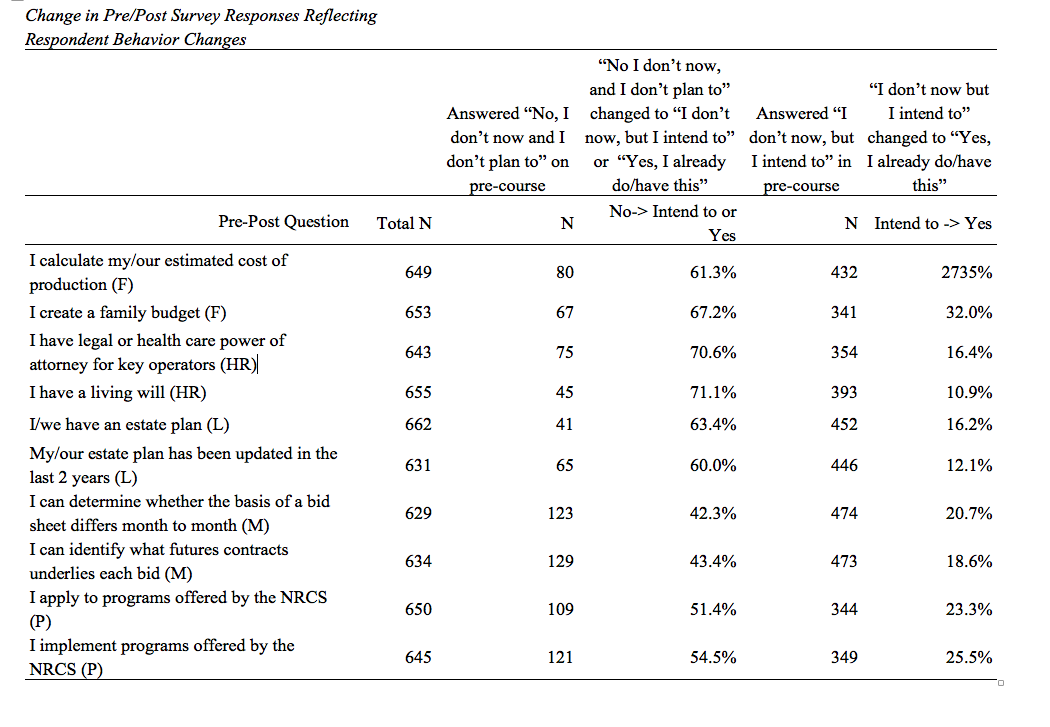

With further analysis, the data indicates women changed their attitudes as well as their behaviors. For example, 80 respondents to the pre-course survey indicated “No, I don’t now, and I don’t plan to” calculate their estimated cost of production. However, 61.3% (n=49) of those respondents changed their response from “No, I don’t now, and don’t plan to” (no) to “Yes, I already do/have this” (yes) or “I don’t now, but I intend to” (intend to). In general, the percentage of participants changing from “No” to “Intend to or Yes” between the pre-course survey and the post-course survey ranged from 42.3% to 71.1% and the percentage of participants changing from “I intend to” to “Yes” ranged from 10.9% to 32.0% (Table 5).

Table 5. Change in pre/post survey responses reflecting respondent behavior changes.

Anecdotal Evidence

Lacy Mason’s story is an example of anecdotal impacts collected by educators in the fourteen states. In 2013, Lacy was thumbing through a seed catalog and hops jumped off the page. At that moment, she embarked on an entrepreneurial journey to grow and market hops in Iowa. Lacy grew her small-scale operation in Sac County to 500 plants in the spring of 2016. She planted new varieties, installed a new irrigation system, and purchased a small harvester. Lacy contacted the USDA Farm Service Agency about insurance for non-traditional crops. She also secured a marketing contract with Midwest Hop Producers, LLC. Lacy has a strong entrepreneurial spirit, but she also credits her 2014 Annie’s Project experience for giving her the confidence to handle the business aspects of starting an agricultural venture. “I never realized how rewarding it would be to have my own business,” she says.

Watch Lacy’s video at www.extension.iastate.edu/womeninag/lacys-story.

For more Annie's Project videos, click here.

Discussion

Annie’s Project educators created positive impacts for women in fourteen states from 2013 to 2015. More than 677 women participated in 76 courses that were collaboratively evaluated with the same survey instruments. Annie’s Project courses were successful in extending knowledge and empowering women to take important risk management actions. Beginning farm and ranch women learned with and from experienced business owners.

Women chose goals for applying what they learned about financial risk management more often than other goals. This new mind-set can lead to improvements in farm profitability and more stable farm family income. The results demonstrate the important role extension educators have in risk management education for women. Extension educators working with this audience can look to Annie’s Project as a model for successful programming.

Women gained knowledge in all risk management topics: financial, human resource, legal, marketing and production. There were positive correlations between the overall knowledge gains from pre- to post- course survey responses and the level of agreement that the Annie’s Project best education practices, key principles and core values were implemented. This suggests survey respondents benefited from the course structure and educational methods used. The best education practices, which were specifically designed to engage women farmers, effectively increased learning. This result demonstrates why the Annie’s Project key principles, core values and other methods identified as compatible with women’s learning preferences are important to delivering high quality educational programs for women in agriculture.

Women of all ages and experience levels can learn to manage business risks by applying research-based knowledge and decision tools. With education and support, Annie’s Project participants changed their behaviors to make better decisions and take important actions to manage agricultural risk. Survey results indicate respondents calculated costs of production, created family budgets, signed up for or implemented Natural Resource Conservation and Farm Service Agency programs, obtained health care powers of attorney and much more.

Annie’s Project brings positive changes and creates public value. When farm and ranch women are empowered, they can help create a more sustainable agriculture by improving economic resiliency, conserving natural resources, and taking on influential roles in their families and communities. These women and their farm and ranch families or business partners learn to make good decisions using the knowledge they’ve gained and the research-based information Extension educators share. Women change their behaviors and take actions to produce safer and more abundant food, which contributes to global food security.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Ruth Hambleton and Annie’s Project – Education for Farm Women for cooperating on this national study to evaluate and share Annie’s Project program impacts. We are deeply indebted to the many educators across the country who cooperated with us to apply the survey protocols and instruments to their local courses. It is with sincere respect that we acknowledge the Iowa State University Extension and Outreach Farm Management Team for their dedication to funding and developing this study; thank you to Charles Brown, Ryan Drollette, Tim Eggers, Shane Ellis, Steve Johnson, Kelvin Leibold, Melissa O’Rourke, and Gary Wright. We would also like to recognize Farm Credit Services of America, the USDA NIFA Extension Risk Management Education Centers, and the USDA Risk Management Agency for their roles in encouraging and supporting this extension work over a number of years.

Literature Cited

Albright, C. (2006). Who’s Running the Farm?: Changes and characteristics of Arkansas women in agriculture. Journal of Agriculture Economics. No. 5, 1315-1322.

Charatsari, C., Papadaki-Klavdianou, A., Michailidis, A., & Partalidou, M. (2013). Great Expectations? Antecedents of women farmers’ willingness to participate in agriculture education programs. Outlook. 42:3, 193-199.

Duffy, M., Johanns, A. (2014). 2012 Study of Farmland Ownership and Tenure in Iowa. Retrieved from: July 26, 2017, http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/extension_pubs/74/

Fenton, G. D., Brasier, K.J., & G.F. Henning. (2010). Status of Women in Agriculture According to the 2007 Census of Agriculture. Journal of Agromedicine. 15:1, 5-6.

Heins, L., Beaulieu, J., Altman, I. (2010). The Effectiveness of Women’s Agriculture Education Programs: A survey from Annie’s Project. Journal of Agriculture Education. 51:4, 1-9

Sachs, C. E., M.E. Barbercheck, K. J. Brasier, N. E. Kiernan, & A. R. Terman. (2016). Rise of Women Farmers and Sustainable Agriculture. Iowa City, Iowa. University of Iowa Press.

Schultz, M. M., Anderson, M. J., Eggers, T., Hambleton, R., & Leibold, K. (2016). A Model for Professional Development: Annie’s Project National Educator Conference. Journal of the National Association of County Agriculture Agents. 9(1). Retrieved from: July 26, 2017, http://www.nacaa.com/journal/

Trauger, A., Sachs, C., Barbercheck, M., Kiernan, N. E., Brasier, K., & Findeis, J. (2008). Agricultural education: Gender identity and knowledge exchange. Journal of Rural Studies, 24, 432-439.

USDA National Agriculture Statistics Service, (2012). 2012 Census of Agriculture; Retrieved from: July 26, 2017, https://www.agcensus.usda.gov/index.php