Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 11, Issue 2 - December, 2018

A Way to Approach Farmer Consultations: Guiding Farmers to Their Own Solutions

- Forstadt, L.A., Associate Extension Professor, Child and Family Development Specialist, University Of Maine Cooperative Extension

Jackson, T.L., Associate Extension Professor, Agriculture & Natural Resources, University Of Maine Cooperative Extension

Sadauckas, A., Farmer, Apple Creek Farm

ABSTRACT

The authors provide an approach for agricultural service providers (ASPs) to work with farmers with an awareness of “relational” topics including communication, decision making, goal setting, and time management. It is grounded in an exploratory, applied research project with farmers in Maine, where relational topics were perceived as valuable. The authors developed a farmer typology with a team of ASPs that considers 1) the farmer’s stage of development and 2) the farmer’s level of competency. A discussion of the development stage and competency level are included, as is a description of the approach for ASPs to be guides.

Introduction

Extension agricultural staff are well versed in their technical areas of expertise and are generally sought out for programming and consultations with farmers in these areas. Topics often include production management, pest management, business planning, soil health, or marketing that focus on economic and environmental impacts of farming. It is less common that non-technical skills, which are sometimes referred to as “social” and what we are calling “relational” skills, are integrated into programming and research (Suess-Reyes and Fuetsch, 2016). The economic costs of a lack of clear communication, decision making, goal setting, and time management are sometimes interwoven into workshops and consultations (Paskewitz and Beck, 2017; Buckley, 2016; Öhlmer et al., 1998). Farm succession, business planning, employee interaction, and marketing are just some of the topics of which relational skills can only improve the outcomes (Suess-Reyes and Fuetsch, 2016). Less common, but not unheard of, are workshops specifically about communication, conflict management, and negotiation that are offered for an agricultural audience. Within Extension, these topics are more commonly found in programming for parenting, community development, and facilitation audiences (Brower and Darrington, 2012; University of Maine Cooperative Extension, 2018).

Agricultural service provider (ASP) refers to an informal and inclusive term for professionals who work with farmers. ASPs are faculty and professionals or other staff from Cooperative Extension and a wide variety of other organizations that include USDA agencies, staff state Departments of Agriculture, non-profits, commodity groups, etc.

Sometimes the reason that farmers do not succeed in implementing change is not a reflection of the quality of the technical information presented, nor the monetary or personnel resources needed to implement the change. Instead, something like incomplete goal setting or difficulty in time management can inhibit the application of a new technique or a change in practice. These reasons are part of farm relationships and the relational skills described above (McShane and Quirk, 2009). Despite the technical content area expertise of the ASP, when they are able to consider a diverse range of reasons why implementation has not occurred or has not gone well, there are more variables to consider for problem solving. ASPs can work with the farmer to identify where problems occurred and identify the technical and relational issues that may need to be addressed (Taylor and Norris, 2004). The need to address relational issues, not just technical content, will not come as a surprise to most ASPs. ASPs familiar with Whole Farm Planning will likely recognize these skills (Henderson and North, 2011). Anecdotally, the most seasoned and well-connected Extension ASPs are often those who are able to develop positive relationships with farmers and connect with them as people, because it is through relationships that trust is built and change is more likely to occur (Kilpatrick et al., 2014).

For the purposes of this project, we identified four relational skills: communication, decision-making, goal-setting, and time management. Each is defined below.

- Communication: Identifying the relationships and roles on the farm and tools to improve communication between family members, farm partners, employees, customers, and other decision makers.

- Decision-making: Utilizing existing tools to prioritize tasks and plan with a clear understanding of management roles and responsibilities, and criteria on what decisions can be made by the person in charge and what require all stakeholders’ input.

- Goal-setting: Develop farm goals that integrate quality of life values and relationship goal criteria into farm decision making.

- Time Management: Utilizing existing resources to assist farmers in optimizing farm roles and responsibilities.

Farmer Competency

Nearly two decades ago, the New England Small Farm Institute (NESFI, 2000) created a curriculum tool that systematically listed duties and tasks performed by farmers in the northeastern United States. This tool was designed based on focus groups with farmers to guide the development of competency-based training programs for beginning farmers. The curriculum includes an extensive list of duties that successful farmers do and tasks that are associated with the duties. For example, the duty “Manage Farm Labor Resources” includes 11 tasks, one of which is “supervise farm workers” that encompasses communication, motivation, and dispute resolution to competently plan for and manage farm labor.

Many of the beginning farmer trainings in the Northeastern United States (including but not limited to Maine, Massachusetts, and New York) use or have used the NESFI curriculum to develop content. The curriculum provides a comprehensive list of duties and tasks of a successful farmer, however, it does not describe how and when in a new farmer’s development they are expected to master the duties and tasks that are described. Further, there is little to no guidance about what to expect nor how to prepare for the associated tasks when skills like communication, decision making, goal setting, and time management are involved. It is important to know how farmers develop and what competency looks like, particularly when relational skills are involved, and how to consider the relational skills is necessary to realistically apply a curriculum that is designed to inform the development of competency-based trainings.

The reason for working with farmers in the relational skills is because they are critical to a farm’s success and the satisfaction of the farmer (McShane and Quirk, 2009). Dr. Robert Fetsch (1995) from Colorado State University Cooperative Extension said, “Ranchers and farmers are telling us their weakest link is not technology nor information. Their weakest link is human relationship management.” To successfully run a farm at a small or large scale, irrespective of the commodity, healthy personal relationships are a necessity. This is true when negotiating responsibilities with family members, developing a business plan with a business partner, arranging deliveries for markets, and interacting with customers (Paskewitz and Beck, 2017). These skills are required in arranging markets, answering questions on and off the farm, and have a role in both in-person and electronic methods of communication.

ASPs need not be experts in relational skills. Instead, by adopting the approach of acting as a guide in their work with farmers, they are more able to view the problem(s) that are identified through various lenses (A. Diffley, personal communication, July 24, 2017). One way is to explore the relational skill(s) in the context of the presented issue.

As an example, consider the following farm scenario. Despite the farmer attending a workshop and receiving some materials for setting up a hoop house, the task is not completed. Through conversation with the farmer, the ASP might realize that it was poor goal setting, lack of time management, and/or inefficient communication that inhibited the timely set-up of the hoop house, preventing fall plantings to supply a winter market. If that is true, then the farmer would benefit from resources and training in the areas of goal setting, time management, and/or communication. Once the farmer has more clear goals and a strategy for time management, they can implement a plan for setting up the hoop house and communicate with the right staff to do so. With improved planning and communication, the planting could be done in a more timely manner, and the product would be ready in time for winter market.

Methods

Farmer Focus Groups

In 2017, we conducted six focus groups with more than 60 farmers about communication, decision making, goal setting, and time management. Each focus group had approximately 10 farmers in it.

- Farmers were asked: Of successful farmers you know, what are some of the qualities about them that you admire and respect?

- They sorted the qualities into the four relational skills categories.

- They responded to a series of questions focused on each of the relational skills.

- They completed a short survey about future training topics.

The information from the focus groups was presented to the ASP work groups.

ASP Work Groups

In the spring and fall of 2017, 24 ASPs participated in one or more of three work groups. These work groups were designed to have ASPs brainstorm skills of successful farmers at different stages of farmer development. For the work groups, multiple sources of information were provided for them to react to including the farmer focus group data, the NESFI curriculum, farmer development stages and farmer learning stages (described in the Results section). Over the course of six months, at each meeting of the work groups, the ASPs responded to materials that were prepared by the authors by providing feedback and suggestions for improvement.

Synthesis

As data became available following the farmer focus groups and ASP work group meetings, the project team combined, overlaid and continually modified the existing NESFI farmer typologies and Dreyfus Model learning stages to create a typology that seemed to more accurately reflect what farmers and ASPS were reporting. Each new iteration was brought to the ASPs for consideration.

Results

This section briefly describes the findings from the farmer focus groups, and the ASP work groups. The final developmental stages and learning stages are presented as part of a “farmer typology” for use by ASPs and famers.

Farmer Focus Groups

When asked what makes a successful farmer, the responses across the focus groups were combined and the most common responses included the non-technical skills of:

- Resilience

- Commitment

- Humility

- Nurturing

- Organization

- Optimism

When surveyed about the project’s specific relational skills, many farmers indicated that these were "very challanging", and there was strong interest in learning more about each one (Table 1).

Table 1. Relational skills categories identified through farmer focus groups. Data are percentages of focus group farmers (n=48) who indicated that each relational skill was "very challenging," as well as their interest in learning more.

| Relational Skills Identified through Farmer Focus Groups | % Farmers Indicating "Very Challenging" | % Farmers Indicating "Very Interested in Learning More" |

| Time Management | 49 | 64 |

| Goal Setting | 21 | 45 |

| Decision Making | 33 | 57 |

| Communication | 29 | 70 |

ASP Work Groups

Prior to the work groups, 52 ASPs responded to a needs assessment survey. Half of them reported “seeing issues with interpersonal skills on farms” they work with. Similarly, over half of these ASPs were “not comfortable” or “somewhat uncomfortable” addressing relational issues in consultations.

The farmer typology was refined over the course of six months. During three work groups, 17 ASPs participated in one or more of the sessions, working with the typology, informing an accompanying training, and providing feedback on a number of resources. All of these materials integrated the relational skills, and were designed to contribute to an increase in confidence of ASPs and their ability to see how relational issues interweave with many other types of issues. This is why the phrase “acting as a guide” is used. ASPs are still content area experts, but they need not be experts in addressing the relational skills. The following farmer typology, incorporating the farmer development stages and the farmer learning stages, was crafted.

Farmer Development Stages

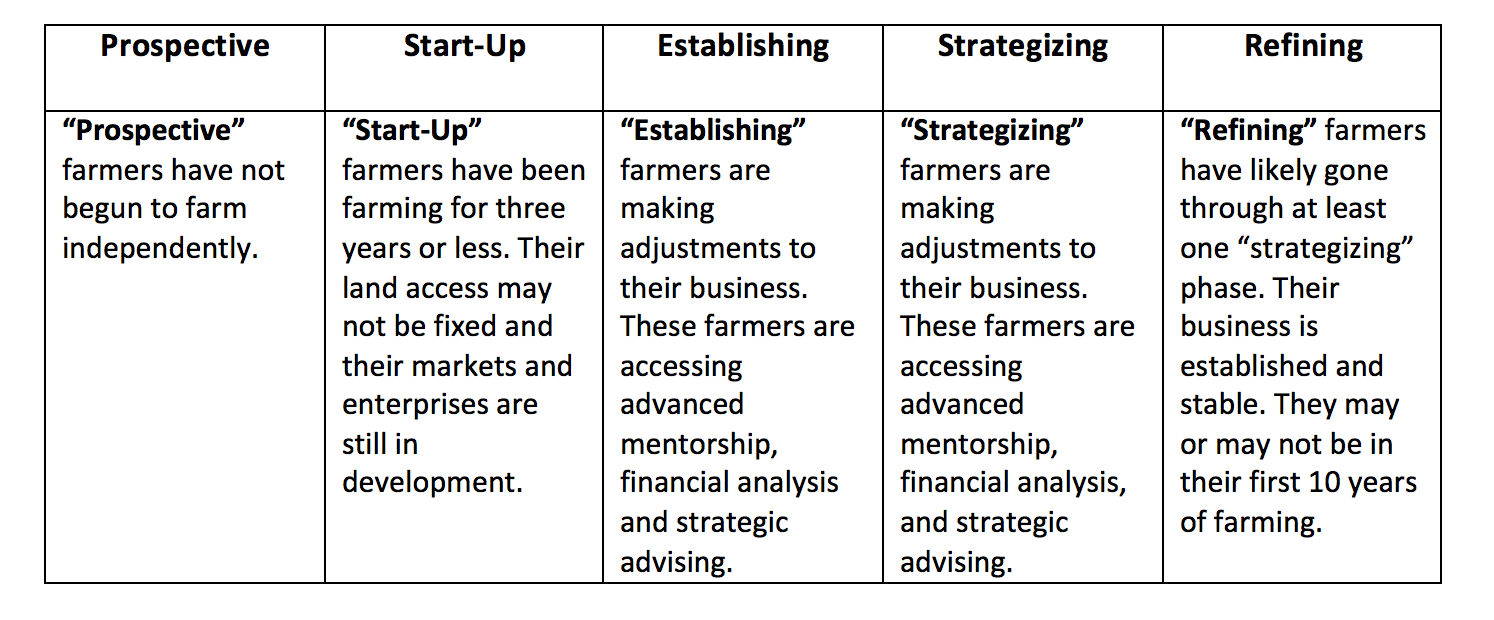

A 2001 publication from the Northeast New Farmer Network Project details a typology of “new” farmers and describes their needs at multiple stages of development (Northeast New Farmer Network, 2001). These authors define new farmer stages as Prospective (recruits, explorers, and planners; not yet farming) or Beginning Farmers (start-ups [years 0-3], re-strategizing, and establishing [years 4-10]). Understanding a farmer’s stage of development is useful to helping guide them to the appropriate resources for their chosen farming path. Table 2 illustrates the stages of farming and provides examples of the years of experience and business practice.

Table 2. Stages of Farming with Examples

Learning Stage

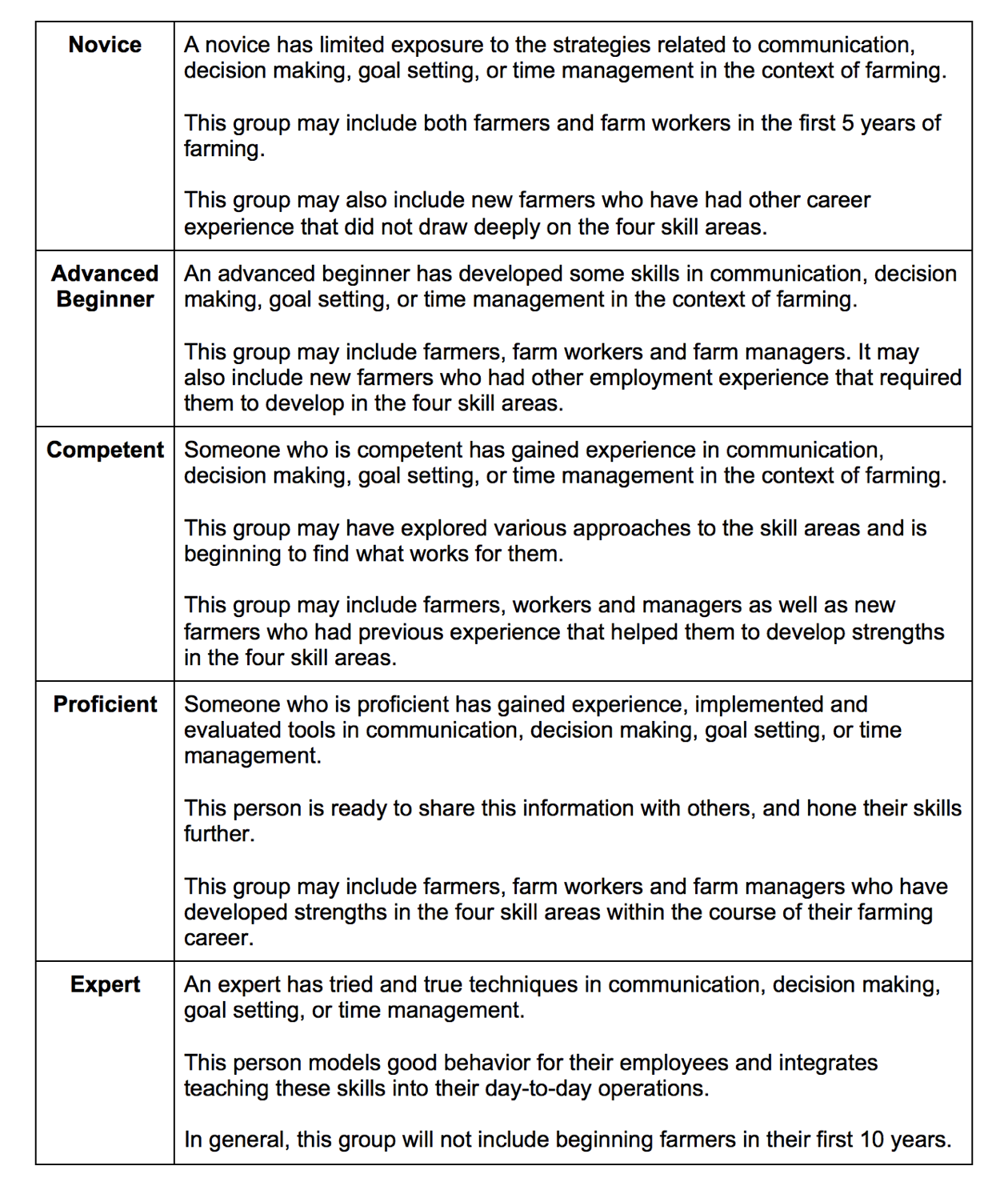

At each stage of farmer development, farmers have a corresponding level of competency for all types of skills (including each of the relational skills) that aligns with a stage of learning. In this project, learning stages are based on the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition (Lester, 2005; Dreyfus,1981; Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 1984). The learning stages range from “novice” to “expert.”

The farmer learning stages describe the level of skill and competence in relationship to a task or enterprise. They can be helpful when thinking about skill acquisition in farmers, because each person will come with a different background, set of interests, and existing skills to put toward their new endeavor. For example, a start-up farmer (the farmer’s development stage) may have no experience with managing employees, but may be well versed in developing and implementing a crop plan. The farmer’s learning stages are novice in human resources, but proficient in crop management.

The Dreyfus model helps understand how a farmer learns and develops competency in new skill areas. A novice has an incomplete understanding, does tasks instantly and without conscious thought or decision, and needs supervision to complete them. An advanced beginner has a working understanding, tends to see actions as a series of steps, and can complete simpler tasks without supervision. Someone who is competent has a good working and background understanding, sees actions at least partly in context, is able to complete work independently to a standard that is acceptable though it may lack refinement. A proficient farmer has a deep understanding, sees actions holistically, and can achieve a high standard routinely. Finally, an expert has an authoritative or deep holistic understanding, deals with routine matters intuitively, is able to go beyond existing interpretations, and achieves excellence with ease.

It can be clear how the levels of skill can be applied when learning something technical. However, this model of skill acquisition is also applicable to the relational skills we have introduced. For example, for some people, goal setting is a well-practiced and proficient activity. For others, it may take formal introduction, guided practice, and a peer network to share experiences to become competent. Table 3 describes the learning stages applied to the relational skills: communication, decision making, goal setting, and time management.

Table 3. Farmer Learning Stages and Relational Skills

Discussion

The goal of this project was to create a typology of beginning farmers for ASPs to have as a resource in their work with farmers. As a resource, typologies are useful to categorize people, and they should be used with caution and in consultation with farmers. When meeting with a farmer and exploring the farmer development stage and learning stage, the farmer’s self-perception is important.

Farmer typologies are not a new concept, but the integration of the farmer typology with the learning stage, and the weaving in of the relational skills is novel. The ASPs in Maine who participated in the work groups became more comfortable with development and learning stages, and in integrating discussion of relational skills in consultations. The ASPs found it was important to reframe their role to be a “guide” rather than an “expert,” and learned how to work with farmers to identify potential issues in communication, decision making, goal setting, and time management.

Applying the Typology

The work groups were one way this information was shared in Maine, and there have been subsequent webinars and trainings to increase the reach in the Northeast. For ASPs, it is useful to consider the farmer development stage and learning stage when working with farmers on any topic. It is also helpful when considering who the audience is for a workshop or training.

When an ASP is aware of the relational skills, they can bring attention to a relational issue that may ultimately be affecting a farm’s viability. Communication, decision making, goal setting, and time management are part of how farmers implement changes and approach solving problems. Even if a recommendation seems easy to implement, if there is a barrier related to talking about the change with a business partner or figuring out how the change fits in to the farmer’s overall goals, then adoption is unlikely (Diffley, 2018). The problem is not access to information, rather, the problem is having the skills to implement a change.

What we propose is that ASPs use the typology to understand more about a farmer. When the farmer’s stage of development is considered along with their learning stage, then the type of recommendations the ASP gives will change. Further, when the learning stage is identified in partnership with the farmer, instead of the ASP making an assessment about the farmer, there are fewer assumptions made and the process of identifying a solution will include tools the farmer already uses. The process for identifying a solution will be appropriate to the farmer’s development and experience.

As an example, consider the following farm scenario. An Extension Educator with a specialty in soil science receives a call from a farmer who is in her fourth year of farming and hoping to expand her farm by an additional two acres to grow pick-your-own-strawberries. She is calling to ask for advice about soil health, variety types, and management strategies.

- Stage of farm development: Start-up

- Learning stage: To determine this, the educator could ask some questions: what are the soil types? How will growing strawberries fit with your existing crop rotations? Will you manage them an annual or perennial crop?

In addition, the educator can ask some further questions that will prompt the farmer to think through her own questions more thoroughly:

- How does this expansion fit in to your whole farm plan? This focuses on goal setting and decision making.

- Have you outlined the expenses and expected profits from this expansion? This focuses on time management and goal setting.

- Are the other decision makers on board? This focuses on communication.

- When will these additional acres be planted and by whom? This focuses on time management and communication.

- Will this crop be sold to existing markets? This focuses on time management and goal setting.

- How will you reach pick-your-own customers? This focuses on time management and communication.

Approaching the farmer client as a guide can therefore expand the range of discussion. A farmer who is a novice in strawberry production will need support on all aspects of production to be successful. In the same regard, a novice pick-your-own farmer will need relational skills support to successfully launch and manage this aspect of their farm. While the farmer may be coming to you as an ASP for your berry growing expertise, the farmer’s stated goal implies other supports are needed as well. Through the expanded approach an ASP might identify other resources critical to farmer success.

Conclusion

Including questions that invoke relational skills provides opportunities for novel problem solving by farmers, and for concerns to be voiced that may not otherwise be stated. When an ASP adds this to their toolbox, the benefits to the farmer increase. Not only does the farmer receive technical information about the reason for the consultation or call, but there can be additional insights about the style and process of communication, decision making, goal setting, or time management. Addressing relational skills encourages a thoughtful conversation as ASPs use their listening skills to guide the farmer to consider other, intangible barriers and strengths related to the issue at hand (Buckley, 2016).

Working as a guide with the typology encourages ASPs to feel confident working without expecting to have expertise in all areas of farm management. The more frequently relational skills are included in the questions posed to farmers, the greater the likelihood of farm success (Diffley, 2018; Buckley, 2016.) If an ASP’s goal is to help farmers achieve their farm vision, then it serves the field well to act as a guides and expand the depth of a farm’s resource team.

Literature Cited

Brower, N., and Darrington, J. (2012). Effective communication skills: Resolving Conflicts. Utah State University. Available at: https://extension.usu.edu/relationships/ou-files/effectivecommunicationskills.pdf

Buckley, J. (2016). Interpersonal skills in the practice of food safety inspections: A study of compliance assistance. Journal of Environmental Health, 79(5), 8-12.

Diffley, A. (2018). Quality of life study guides and downloads. Available at: https://atinadiffley.com/quality-of-life/

Dreyfus, S. E. (1981). Four models v. human situational understanding: Inherent limitations on the modelling of business expertise. USAF Office of Scientific Research, ref F49620-79-C-0063.

Dreyfus, H. L. and Dreyfus, S. E.(1984). "Putting computers in their proper place: analysis versus intuition in the classroom," in D. Sloan (ed.) The computer in education: a critical perspective. Columbia NY: Teachers' College Press.

Fetsch, Robert J. (1995). Family Relationships and Estate Transfer – What Should and Can We Do? Range Beef Cow Symposium. Paper 197. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/rangebeefcowsymp/197/

Henderson, E., and North, K. (2011). Whole-Farm Planning: Ecological Imperatives, Personal Values, and Economics. Northeast Organic Farming Association. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Kilpatrick, S., Willis, K., Johns, S. and Peek, K. (2012). Supporting farmer and fisher health and wellbeing in ‘difficult times’: Communities of place and industry associations. Rural Society, 22(1), 31-44, DOI: 10.5172/rsj.2012.22.1.31

Lester, S. (2005). Novice to Expert: The Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition. Available at: http://devmts.org.uk/dreyfus.pdf

McShane, C.J., and Quirk, F. (2009). Mediating and moderating effects of work-home interference upon farm stresses and psychological distress. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 17(244-250).

New England Small Farm Institute. (2000). DACUM Occupational Profile for Northeast Small Scale “Sustainable” Farmer. Columbus, OH: Center on Education and Training for Employment. Available at: http://www.nebeginningfarmers.org/files/2012/05/dacumchart-28vyp6m.pdf

Northeast New Farmer Network. (2001). Gaps in new farmer programs and services. NESFI: Northeast New Farmer Reports. Available at: http://www.smallfarm.org/uploads/uploads/Files/GAPS_IN_NEW_FARMER_PROGRAMS.pdf

Öhlmer, B., Olson, K., and Berndt, B. (1998). Understanding farmers’ decision making processes and improving managerial assistance. Agricultural Economics, 18(1998), 273-290.

Paskewitz, E.A., and Beck, S.J. (2017). When Work and Family Merge: Understanding Intragroup Conflict Experiences in Family Farm Businesses, Journal of Family Communication, 17(4), 386-400), DOI: 10.1080/15267431.2017.1363757

Suess-Reyes, J., and Fuetsch, E. (2016). The future of family farming: A literature review of innovative, sustainable and succession-oriented strategies. Journal of Rural Studies, 47(2016), 117-140.

Taylor, J.E., and Norris, J.E. (2004). Sibling relationships, fairness, and conflict over transfer of the farm. Family Relations, 49(3).

University of Maine Cooperative Extension. (2018). Strengthening Your Facilitation Skills. Available at: https://extension.umaine.edu/community/strengthening-your-facilitation-skills/level-1/