Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 11, Issue 1 - June, 2018

Effectiveness of On-farm Classes for Addressing Farmer Training and Farmer Networking Needs

- Bramwell, S. G., Agriculture Extension Faculty, Washington State University

ABSTRACT

Extension educators must be adept at developing programming in response to diverse needs. One strategy to tackle this may be to develop multi-functional programming. The extension work reported here combined a technical class series with farm tours and on-farm teaching to address both farmer requests for technical training and networking. A small-ruminant health class was held in barns at farm sites, and included a farm tour, lecture, and networking. The course evaluation indicated that holding a technical series on farms, and including farm tours achieved the desired multiple outcomes. Eighty-eight percent of participants increased knowledge while 86 percent agreed that networking was facilitated. Among three types of networking evaluated, participants felt that networking with fellow farmers was facilitated the most.

Introduction

Extension educators must be adept at managing and prioritizing programming in response to what can be highly diverse constituent needs. One strategy may be to consciously develop multi-functional programming that can serve multiple needs at a time.

Results from various needs assessments demonstrate that the extension educators, whether new or experienced, encounter more need for programming than they have time or other resources to deliver. By turn, new farmers (Dill et al., 2014; Byler et al. 2013), aging farmers (O’Neil et al., 2010), women-owned farm operations (Barbercheck et al., 2009), and urban as compared to rural farmers (Oberholtzer et al., 2014; Ekanem et al., 2001), among others, all generate different and diverse needs responses. Results from a farmer evaluation in Thurston County, WA, conducted in this case as part of a first-year, new faculty needs assessment, generated 235 comments from 92 participants (including 83 farmers), across ten thematic needs categories. While needs statements included many topic-specific issues such as access to water rights transfer services and equipment-sharing schemes, among others, needs related to training, education, networking and information resources received the most (120) comments.

To address this diversity, the extension work reported here attempted to combine a 6-session technical class series with farm tours, and on-farm teaching. The aim was to simultaneously serve two high-ranking needs: (1) specific farmer requests for technical training (in this case the topic of small-ruminant livestock health was selected), and (2) explicit requests for farmer-farmer networking opportunities. While any workshop or farmer-oriented class provides an opportunity for networking, four of the six sessions were offered in barns at commercial livestock operations, and combined with a farm tour and networking opportunities. The class series was subsequently evaluated to determine the effectiveness of on-farm classes combined with farm tours to achieve instructional and networking outcomes.

Methods

A six-class technical farm management series was developed in spring 2017 for implementation in September and October. Results from a needs assessment conducted by Bramwell et al. (2017) identified technical training as a priority need among producers, and follow-up interviews narrowed the focus to small-ruminant livestock health. An instructor was identified with experience both in small ruminant production and veterinary sciences. In this case the instructor was a veterinarian of 28-years with background in raising lambs.

A syllabus was developed by the extension educator and course instructor. Subject matter focused on nutrition, reproduction, parasite control, vaccinology and infectious diseases, managing medications and antibiotics, humane euthanasia, and metabolic and toxicological diseases. On-farm sites were selected for four of the six class sessions, with the two remaining sessions (weeks one and six) held at the County Extension office. Hosting farms included a small-scale, direct-marketing pasture-based sheep operation, the teaching farm for a local FFA sheep chapter, a sheep dairy operation that produces award-winning artisanal sheep cheeses, and a small-scale meat goat operation. The class started on September 6th and ended on October 11th, and occurred from 6-8:30pm on Wednesday evenings. The course fee was $150 per participant. A flier was circulated 6-weeks before the course utilizing a County Extension farmer email list, a County Extension newsletter, fliers posted at farm-related businesses, and a County Extension social media page.

Class sessions included a tour of the farm, question and answer with the instructor and business owner, and minimal hands-on activities. Classes were held in barns at the commercial farm sites, and the high school classroom at the FFA site. Light refreshments were provided, and some time was afforded for farmer networking before and after the class, and during breaks.

Course evaluation consisted of an anonymous two-page survey consisting of 14 closed-ended questions and two open-ended questions. The survey was administered at the end of the last day of class, and participants were provided in-class time to complete it. Survey questions solicited information on farmer age, ethnicity, gender self-identification, experience raising livestock, change in confidence regarding maintaining small ruminant health, knowledge changes across technical subject matter categories as outlined in the syllabus, plans to utilize information obtained, responses to the course format, preference for the balance of on-farm and in-class sessions, instructor contributions to participant learning, and feedback on how to improve the course.

Evaluation questions and participant responses regarding the course format specifically were divided into three categories, those regarding (a) the networking value of the format, (b) the ability of the format to facilitate learning, and (c) how the format impacted participant satisfaction (Table 1). Upon completion, participant evaluations were collected. Response data was entered into Qualtrics Software (Qualtrics, 2016) for compilation and analysis.

Table 1. Questions evaluating the impact of course format on networking value, learning facilitation and participant satisfaction. Evaluation questions were answered as the degree to which students agreed or disagreed with each statement.

|

Networking value |

|

Facilitated networking with host farms Facilitated networking with fellow farmers/students Enabled connections in the community I would not have made on my own |

|

Learning facilitation |

|

Made it easier to learn technical subject matter Deepened my understanding of technical subject matter |

|

Student satisfaction |

|

Made it easier to take an evening class at all after a busy day |

|

Made the class a more enjoyable experience |

Results

Participant characteristics

Twenty-eight participants enrolled in the course, and 23 completed evaluations for an 82 percent completion rate. The average participant age was 41, and those 50 years-old and above constituted the largest age bracket. Sixty percent of participants were female, and 40 percent were male. Seventy percent didn’t grow up raising livestock and most had ten years or less of experience.

Participant knowledge change

Most participants (88 percent) moderately to greatly increased knowledge by taking the course, and 99 percent planned to apply knowledge gained across all topic categories. Eighty-five percent of participants either somewhat or strongly agreed the class increased their confidence in maintaining ruminant livestock health (54 percent strongly, 31 percent somewhat). Sixty-two percent of participants significantly to greatly increased knowledge in the following subject matter: nutrition, reproduction, parasite management, vaccinology, medications, pain management, metabolic and toxicological disorders (Table 2). Ninety-nine percent of participants reported they will use the information on their farms. Participants reported wanting to learn more about, by order of ranking: balancing feed rations, grazing systems, administering medical treatment and forage analysis.

Table 2. Proportion of participants (%) who increased knowledge by topic area.

|

|

No increase |

Small increase |

Moderately increased |

Significantly increased |

Greatly increased |

|

Nutrition |

23 |

32 |

32 |

14 |

|

|

Handling and management issues |

27 |

32 |

18 |

23 |

|

|

Reproduction |

5 |

41 |

36 |

18 |

|

|

Internal parasite control and management |

23 |

36 |

41 |

||

|

External parasites |

5 |

32 |

23 |

27 |

14 |

|

Vaccinology and infectious diseases |

5 |

23 |

41 |

32 |

|

|

Wise use of medications, especially antibiotics |

9 |

23 |

36 |

32 |

|

|

Pain management and welfare issues. Euthanasia. |

25 |

45 |

30 |

||

|

Metabolic and toxicological diseases |

20 |

50 |

30 |

||

|

Average |

1 |

11 |

27 |

36 |

26 |

Course format

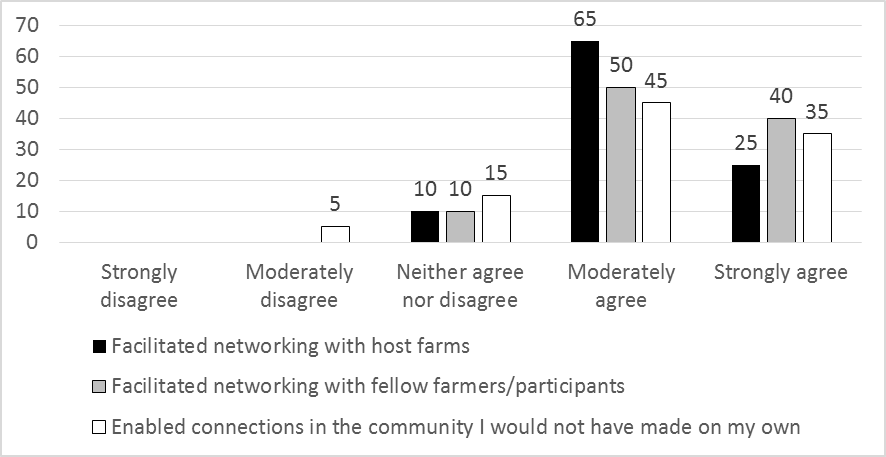

The greatest proportion of participants moderately agreed that a course format which located technical instruction on farms, and combined this instruction with a farm tour, altogether facilitated networking, participant learning and participant satisfaction (44 percent moderately, 40 percent strongly). An average 86 percent of participants (Figure 1) agreed that the course format facilitated all types of networking (53 percent moderately and 33 percent strongly, expressed as averages across the three networking types). Among the types of networking evaluated, participants felt that networking with fellow farmer-participants was facilitated the most. The same proportion of participants (90 percent) agreed either moderately or strongly that host farm networking and farmer-to-farmer networking were facilitated. Yet more participants (40 percent) agreed strongly that farmer-to-farmer networking was facilitated, compared to 25 percent of participants who agreed strongly that host farm networking was facilitated.

Figure 1. The impact of course format on networking value, as measured by percent agreement with evaluation statements.

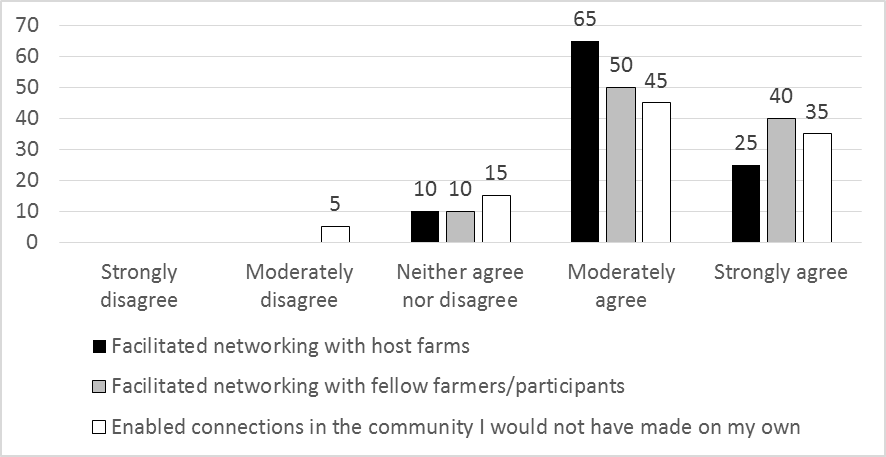

Participants generally agreed, whether moderately or strongly, that the course format facilitated learning and enhanced participant satisfaction (Figure 2). Most distinctively, 58 percent of participants strongly agreed that the format made the course more enjoyable. By comparison, a relatively even number of participants (40 to 45 percent moderately and strongly, respectively) agreed the course facilitated technical learning and taking a course after a busy day.

Figure 2. The impact of course format on learning facilitation and participant satisfaction, as measured by percent agreement with evaluation statements.

In comments on how the course could be improved, participants offered useful critiques. These included:

- Too much time required to travel to and from dispersed farm sites.

- Farm sites should be “exceptional, and not just ok” to merit a visit.

- More hands-on opportunities, including administering drenches, use of medical equipment, hoof trimming, restraints.

- More class time, less farm tours.

- More focus on nutrition and grazing management.

- “I stay quiet, so I don’t network well”.

While on-farm class sessions involved presentations in cooler temperature barns, less comfortable seating, potential livestock distractions, and glare from the sun setting, no participants agreed that the course format was a distraction. Asked about the balance of classes at farm sites versus an Extension conference room, 65 percent of participants recommended that two-thirds or more of classes should be held at farm sites, 15 percent suggested an equal amount, and 20 percent suggested two-thirds or more should be held at an Extension meeting space.

Discussion

As a multi-functional programming tool, holding a technical class series on farms, and including farm tours, did achieve multiple outcomes of providing information resources and networking opportunities. Knowledge gain was not hampered, and by contrast participants felt the format improved their learning of technical subject matter while improving their overall satisfaction with the class. While participants agreed that networking of all kinds was facilitated by the course format, evaluation data was not conclusive as to whether the networking value was better than if the class had been held at the extension office. Possibly reflecting the high value that farmers place on networking and interactions with other farmers (Crawford et al., 2015), the importance of simply learning on farms was most strongly revealed in overall participant enjoyment of the class.

These results can be used to spur selection of a broader range of teaching formats for extension programming, and to derive greater value from single events. Most extension programming, to some degree, is multi-functionality by default. However, expected outcomes from tried-and-true activities may be expanded with additional planning and creative thinking. On-farm learning, for instance, can go beyond demonstrations and field days. An example would be technical instruction on wise use of antibiotics in a barn-classroom, followed by livestock handling practices. Likewise, farmer networking can go beyond mixers and farm walks. Examples would be offering a meal as part of a lecture or workshop, coordinating a discussion on farmer equipment needs, and combining a technical workshop with a social gathering to follow. Considered creatively and deliberately, there are endless combinations for multifunctional programming. These results specifically suggest that farms themselves make good classrooms for technical instruction, while more networking value can be derived from an extension workshop if explicitly planned for.

The format, however, does need to be applied with care. More explicit networking opportunities, beyond interaction during farm tours and mingling over refreshments, are needed to further enhance networking outcomes of traditional instruction sessions. This may be particularly important for individuals less likely to interact outside of their comfort zone. Evaluation of on-farm class series could then solicit more detailed and useful information on participant-farmer perspectives on networking that is so valued by this population.

Literature Cited

Barbercheck, M., Brasier, K.J., Kiernan, N.E., Sachs, C.S., Trauger, A., and Findeis, J. (2009). Meeting the extension needs of women farmers: A perspective from Pennsylvania. Journal of Extension 47(3).

Bramwell, S.G., Moorehead, S., Meade, A., Sero, R., Gray, S., and Nowlin, M. (2017). South Puget Sound agricultural producer needs assessment. Retrieved from: https://extension.wsu.edu/thurston/agriculture/2017-south-puget-sound-agricultural-producer-needs-assessment/.

Byler, L., Kiernan, N.E., Steel, S., Neiner, P., and Murphy, D.J. (2013). Beginning farmers: Will they face up to safety and health hazards? Journal of Extension 51(6).

Crawford, C., Grossman, J., Warren, S.T., Cubbage, F. (2015). Grower Communication Networks: Information Sources for Organic Farmers. Journal of Extension. 53(3).

Dill, S., Shear, H., Beale, B., and Hanson, J. (2014). Maryland beginning farmer needs assessment. Retrieved from: http://extension.umd.edu/sites/extension.umd.edu/files/_docs/programs/newfarmer/BFSComparativeNeedsAssessmentFULL.pdf.

Ekanem, E., Singh, S., Muhammad, S., Tegegne, F., and Akuley-Amenyenu, A. (2001). Differences in district extension leaders’ perceptions of the problems and needs of Tennessee small farmers. Journal of Extension 39(4).

Oberholtzer, L., Dimitri, C., and Pressman, A. (2014). Urban agriculture in the United States: Characteristics, challenges and technical assistance needs. Journal of Extension 52(6).

O’Neil, B., Komar, S.J., Brumfield, R.G., and Mickel, R. (2010). Later life farming: Retirement plans and concerns of farm families. Journal of Extension. 48(4).