Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 12, Issue 1 - June, 2019

Learning and Research Beyond the Fence

- Hutchinson, M., Extension Educator, University Of Maine Cooperative Extension

Martineau, E, Master Gardener Volunteer, University of Maine

ABSTRACT

The Maine State Prison is a maximum security facility with over 1000 offenders. The University of Maine partnered with the corrections facility to provide horticulture educational opportunities that develop meaningful job skills and provide a sense of purpose while incarcerated. The program included hands-on learning and research. Over the past 5 years offenders have planted, tended and harvested over 55,000 pounds of food. Master Gardener volunteers and farm crew members develop research/demonstration projects as a way to further develop critical thinking skills and to answer production questions in this unique environment. The program goals are to reduce recidivism and supply the horticulture industry with a semi-skilled work force.

Learning and research can happen in the most unexpected places with magnificent outcomes, for example at the Maine State Prison. The Maine State Prison (MSP), a maximum-security facility, is home to over 1000 offenders. Fresh fruits and vegetables are a welcome addition to their diet. Since 2014, offenders have been producing fresh vegetables and fruits within the confines of the facility on approximately 2 acres. These are small plots interspaced among the housing units, walkways and activity building. Plots are managed with very limited equipment due to security risk. The “farmers” are either Master Gardener volunteers or part of a paid horticulture program. The program goal is to cultivate fresh produce annually for the facility food service center and local food pantries while increasing job skills or a sense of purpose for the participants.

As part of the program, the University of Maine Cooperative Extension provides horticulture education programming to the farmers. A horticultural vocational training (HVT) or a Master Gardener volunteer (MGV) program has been offered most years to eligible and interested inmates since 2001. Participation in educational programs has been shown to reduce behavioral issues within the prison and reduced recidivism. According to Vera Institute of Justice report (2016) inmates who participate in educational programs in prison are 43% less likely to return to prison. The current recidivism rate in Maine is 60 percent. The goal of this program is to transfer horticulture knowledge and develop employable skills. These are skills offenders can use to find meaningful work, when released, that pays a livable wage. Work skills include oral communication, team-work, critical thinking and problem solving. Academic skills include interpreting a soil test, calculating fertility applications, plant variety selection, compost process, starting seeds, transplanting, weed management, crop harvesting and post harvest management, and understanding of good agricultural practices. They also learn about pest management and identification.

In 2018, twelve inmates participated in a MGV program. There are three components to becoming a certified Master Gardener volunteer in this facility. Participants must attend 35 hours of classroom instruction, respond in writing to 65 questions on a variety of horticulture topics, and complete 40 hours of volunteer time. They must also maintain appropriate behavior with no disciplinary actions. Participants wondered if they could conduct research at the facility that would enhance yields and potentially benefit other growers. This created an opportunity to further develop job skills through applied research. I did not know if the MSP staff would be supportive of this idea because this was a maximum-security prison, but the administration and staff supported the concept with a resounding "yes". The administration understood that hands-on research is a very effective tool to develop critical thinking and problem solving skills. Hence a program was developed to include research as part of the horticultural training. Several participants choose to conduct and report research for their volunteer hours.

Methods

Three assessment methods were used to determine program impact: behavior violations, recidivism and program involvement and evaluations. Maine state prison records were used to determine offender behavior changes. Offenders before and after enrollment records were examined for rule violations or new infractions to the law. Internal records are only accessible to MSP staff. The data collected was total number of violations prior to enrollment versus violations afterwards. No names were associated with the records. Both minor and severe infractions were included.

Determining how many utilized their new skills to find meaningful employment would be another assessment tool. However, due to confidentiality rules, MSP and education staff are not allowed to ask for contact information or monitor offenders upon release. Offenders are provided Extension contact information to voluntarily provide information about employment and the impact of the MGV program. Recidivism is a method to indicate behavior modification. Maine State Corrections determines recidivism throughout the Maine corrections facilities. This data is available through public documents.

Program involvement was measured by the number of participants who completed the three components of the MGV program. To accomplish the three components to become a certified Master Gardener Volunteer, ten sessions of classroom instruction were conducted. Weekly classes were held on a wide variety of horticulture topics and taught by University of Maine Extension faculty. Topics in the program included soils, botany, compost, plant diseases, insect pests, small fruit production, vegetable production, greenhouse management, annual and perennial production, and crop rotation. A written exam of 65 questions provided another learning experience to explore some topics not covered in the classroom. Each participant was expected to achieve at least 40 hours of volunteer time within 1 year. The MSP staff monitored volunteer time. Conducting research was considered part of their volunteer time. Their research methods are included because of the uniqueness of doing research inside a maximum secure prison and demonstrates their skill development.

A discussion on using the scientific method and developing a researchable question was initiated with participants to develop research project proposals. Participants drafted research proposals that included rationale for the research; researchable question; hypothesis; research method and design; materials list; and expected completion date. Questions were asked about current production practices. Were the current practices maximizing production? What could they do differently to increase yields? In developing the written proposals they needed to keep in mind the limitations of gardening at a maximum secure facility. Two written project proposals were developed and presented to MSP and University of Maine Extension staff. Each proposal was discussed on its merit and likelihood of success. Even though both projects were very worthy, only one was chosen because of space and staff limitation within the facility. “Growing peppers in raised beds with different rates of compost as a soil amendment” was the project selected. All activities were initiated, developed and managed by offenders.

In the past, garden plots had been amended with compost but application rates were not measured, and recommended rates were not known. The compost used in the vegetable production system was made on-site using organic material from the dining facility and horse bedding. The facility makes between 200-250 cubic yards of finished compost per year. Compost is applied to garden plots either in the spring or fall. The native soils are very poor, shallow to bedrock with very low organic matter and fertility. Because compost is limited, offenders wanted to make sure they optimized the benefits of the compost to maximize production yields by amending with appropriate rates. They developed a researchable question: What rate of compost optimizes pepper production in a raised bed system? Raised beds allowed them to better control the plant media volume and growing conditions. From past studies we know that responses to composts are often more pronounced when crops are grown less intensively or are under environmental stress (Roe, 2001). Raised beds created both conditions.

The compost is made within the facility using a turned windrow system. Compost feedstocks are food scraps, horse bedding, sawdust, and shredded paper. Each feedstock has been analyzed to determine a compost recipe of 2.5 parts horse bedding to 1 part food scrap and shredded paper. Finished compost and soil samples were analyzed at the University of Maine Soil Analytical lab using standard methods. Compost analysis is reported on an as is basis: C:N ratio 11.7; pH 7.4; 40.3 % moisture; bulk density 1010 lbs./cu yd.; conductivity 3.4; and NPK ratio of 2:1:1. The nitrogen in the compost is primarily in the organic fraction. Organic N sources, including SOM, will go through a mineralization process in which soil microbes metabolize organic carbon (C) and convert organic N compounds into ammonium and a subsequent process that quickly oxidizes the ammonium to nitrate (nitrification) (Gaskell and Smith, 2007). Nitrate is the most readily available form of plant nitrogen.

The soil used in the raised beds was a Boothbay silt loam (Natural Resource Conservation Service Soil Survey 1987). The soil pH was 6.1. Other soil parameters, P, K, Ca, Mg, organic matter were satisfactory or optimal for plant growth.

The raised beds were 5’ x 5’ x 1.5’ made from pressure treated lumber. Raised beds were filled with approximately 1.5 cubic yards of growing material. The material was a percentage of soil and finished compost. Bed #1 was 100% native soil considered to be the experimental control. Beds #2, 3 and 4 were amended with 10%, 25% and 50% finished compost, respectively, mixed with the remaining volume of soil.

Intruder pepper (Capiscum annuum) transplants, a bell type pepper, were transplanted the first week of June. Ideally this would have been a replicated study but space was limited. However, there were 16 plants per raised bed that provided a large data set to assess trends. No additional fertilizers or amendments were added during the growing season. Transplants were watered at transplanting and as needed during the growing season. Raised beds were in full sun. Marketable yield, number and total weight of peppers was collected and recorded from each plant. Plant height, stem diameter, number of fruit buds, and pepper sets were also recorded. There were no significant disease or insect issues during the growing season. Bed #1 did experience tunneling from rats early in the season. Tunnels were filled and this did not appear to affect the plants growth.

Program evaluations were used to determine impacts. All aspects of the program were evaluated through written comments and small group discussions. This was particularly important for long-term offenders who might never be released from the system. While program objectives focused on developing job skills, the evaluation process provided a means for participants to express how this program helped with the day to day reality of being incarcerated.

In a maximum secure prison facility there are numerous obstacles educators and participants need to understand and navigate when conducting educational programs. Volunteer time is determined by the schedule of the entire prison work and recreation system. This limits garden access to two 2.5 hrs blocks in the morning and afternoon. Inmates are not allowed to use many typical garden tools for example; metal hand tools, drip irrigation, stakes and pesticides because of security concerns. Participants have limited access to technology and no internet access for research or communication. Communication is limited between offenders and Extension staff, so having clear and reasonable expectations at the beginning of the project was important for success. Written documentation provided important opportunities for offenders to practice written communication.

Results and Discussion

Prior to participation in the program participants had 16 disciplinary actions. There were only 2 disciplinary actions post-participation over the same length of time. Inmates and staff contributed this to a sense of ownership in their learning and feeling part of a community. During follow-up interviews offenders expressed that this program gives them hope, a purpose for getting up and satisfaction of helping others. Another commented “I’m too tired at night to cause problems." In program evaluations, participants stressed the importance of increased job skills as a means to gainful future employment. Six have been hired on the prison farm crew because of this program.

The staff also noticed differences in the participants. One staff member wrote, “The expectations for this position is the same as working on the outside: do quality work, be self-motivated, and use good communication skills to ensure everything is done correctly and the same way. The added benefit of working for a common goal gives the prisoners the opportunity to succeed as a team, which gives them the feeling of self-worth and positive outcomes. Which for many of the guys here, they have never had this opportunity before.”

In 2018, eleven of twelve MGV participants successfully completed all three required components, earning the title of Master Gardner volunteer. They volunteered over 1080 volunteer hours, conducting research and growing over 1200 pounds of vegetables and fruit for local food pantries, including peppers from their research trials.

Participants demonstrated their new job skills by contributing to this manuscript, developing research projects, and increasing crop yields with improved best management practices. Produce yields have increased every year. In 2018, the increase was over 400 pounds.

Tracking recidivism on specific offenders is difficult because of confidentiality laws. Even with permission from participants we have not been successful at connecting with participants upon release. Most want to disassociate with the time they were incarcerated. Maine Department of Corrections does maintain overall recidivism rates but individual recidivism is not public information. However, there has been no known recidivism with the participants, meaning none have returned to this Maine State prison facility.

Horticulture training and research in a maximum security prison provided opportunities for offenders to improve their job skills, produce fresh produce for healthier diets, while providing meaningful information for them to improve yields. The research component of this training provided multiple pathways for participants to develop and improve job skills. The following results and discussion of their research project demonstrates their competency.

All of the data was collected and recorded by the MG volunteers and farm field crew. Data were hand recorded in the field and transferred to a spreadsheet in Excel. For several team members this was a new skill. They also learned to think critically while developing methods to measure, count and weigh the plants and produce. They were limited in the use of computers, scales and other tools commonly available to farmers and researchers. Their creative thinking allowed them to collect meaningful and useful data on the use of compost as a soil amendment.

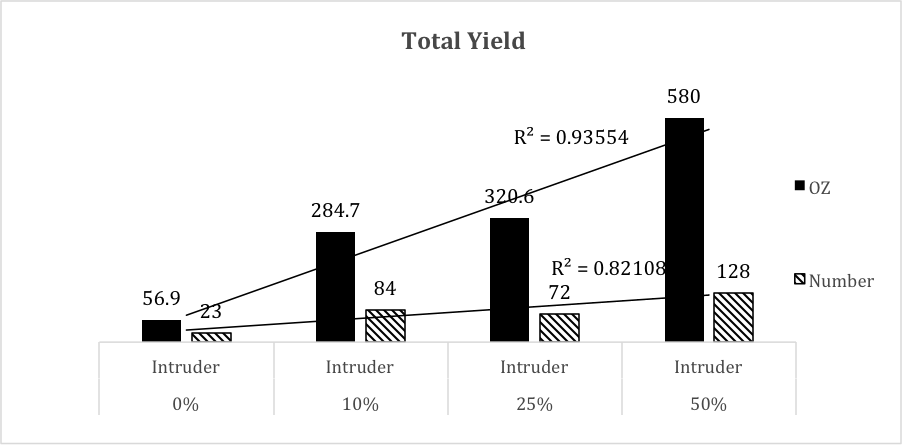

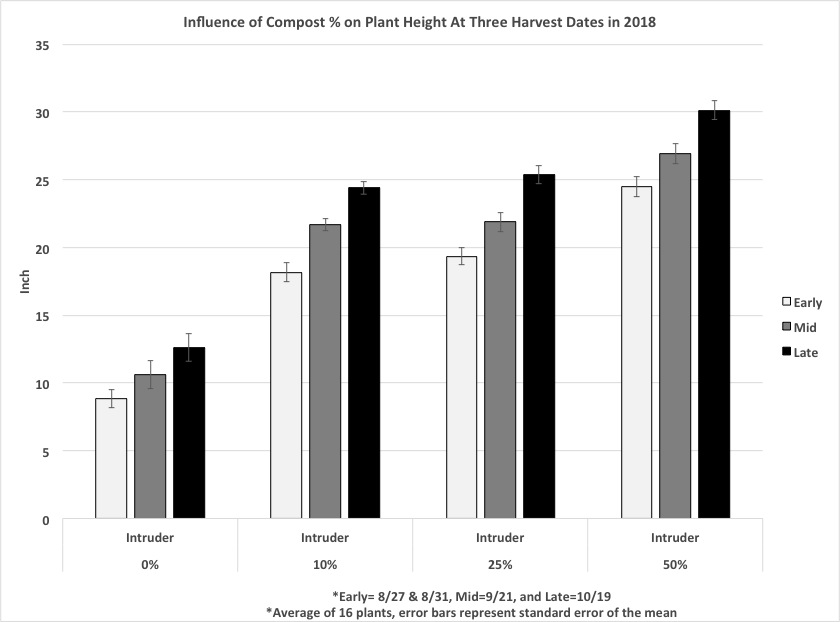

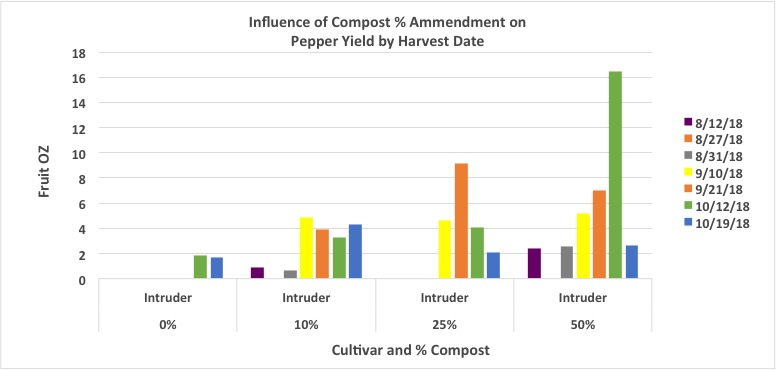

Data was collected from each individual plant then combined for each treatment. Averages per treatment were compared for total yield in ounces, total number of marketable peppers, plant height and yield by harvest date (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Trend lines, for the averages, indicate a positive response to increased compost applications for each parameters measured. Application rates of 10 and 25% had similar responses to total yields and plant height. Peppers matured later at the 50% compost rate (Figure 3). Delayed maturity may have been an effect of the increased N provided by the higher compost rate. Increased levels of the N can cause pepper plants to grow in the vegetative stage longer before producing flowers and setting fruit, thus delaying fruit harvest.

All of the marketable produce was used by the MSP food service and served to the general population.

Figure 1. Influence of percent of compost on total yield. Yield is expressed as weight (oz.) and number of marketable fruit, and as totals from sixteen plants harvested 7 times, August-October, 2018.

Figure 2. Influence of percent of compost on plant height. Plant height was measured on three harvest dates: early= 8/27 & 8/31; mid=9/21; and late=10/19.

Figure 3: Influence of percent of compost on yield by harvest date. Data are expressed as average oz. fruit/plant.

Observation by the participants indicated that raised bed #1, the control, was often dry and did not retain water (Figure 4). Raised beds #2, 3, and 4 (Figures 5, 6 and 7) were observed to hold water and required less water during the season. Though there were no direct measurements of water retention, plant stem and foliage growth were noticeably different between the beds early after transplanting (Figures 4-7; photos on same day in July). This is consistent with Pandy and Shukla (2006) who found that soil moisture in a compost-amended field was consistently higher than in a field with no compost amendment.

Figure 4. Raised Bed #1: control with no compost amendment or other plant nutrients.

Figure 5. Raised Bed #2: 90% soil and 10% compost.

Figure 6. Raised Bed #3: 75% soil and 25% compost.

Figure 7. Raised Bed #4: 50% soil and 50% compost.

Compost appears to have made a difference in the yield of Intruder pepphers. The compost soil amendment rate of 50% provided the highest total yield. However, 10% and 25% also had increased yields over no compost. The 50% application yield increase may have been because this was the first time compost had been added to this raised bed. Over time additional application rates of 50% may not result in the same yield response in these raised beds. In a long-term high tunnel compost research using tomatoes and cucumbers, no response to increased annual amendments of high rates of compost was observed (Hutton and Hutchinson, unpublished data 2018). Instead, there was marked decrease in yield. Commercial operations would need to balance the cost of increasing compost rates and the yield potential for their particular soils.

The research program challenges offenders to use critical thinking, problem solving, and communication skills while building self-confidence. These men are proud of their accomplishments in developing meaningful job skills and have a positive view of how they can contribute to their communities now and in the future.

Literature Cited

Delaney, R., Subramanian, R., and Patrick, F. (2016). Making the grade: Developing quality post-secondary education programs in prison. New York: Vera Institute of Justice

Gaskell, M. and Smith. R. (2007). Nitrogen sources for organic vegetable production. HortTech 17(4):431-441.

Hutton, M. and Hutchinson, M. (2018). Long-term high tunnel compost soil amendment trials. Unpublished data, University of Maine.

Natural Resource Conservation Service Soil Survey: Maine. (1987). Knox and Lincoln Counties. https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/

Pandy C. and Shukla, S. (2006). Effects of composted yard waste on water movement in sandy soil. Compost Science and Utilization14(4):252-259.

Roe, N.E. (2001). Compost effects on crop growth and yield in commercial vegetable cropping systems,.Compost Science and Utilization 2(1):88-96.

Acknowledgements:

Without the support of the Maine State Prison staff and administration this project would not have been possible. I would like to recognize Warden Randall Liberty, Captain Ryan Fries and the rest of the staff for their commitment to this program. I would also like to recognize all of the MG volunteers and farm crew who contributed to the program, especially John Clark, Dennis Dechaine and co-author Eugene Martineau.