Journal of the NACAA

ISSN 2158-9429

Volume 12, Issue 1 - June, 2019

Results of a Needs Assessment of Urban Farmers in Maryland

- Little, N. G., Extension Agent, University Of Maryland Extension

McCoy, T., Assistant Director of Evaluation, University of Maryland Extension

Wang, C, Coordinator of Program Development and Evaluation, University of Maryland Extension

Dill, S. P., Extension Principal Agent, University of Maryland Extension

ABSTRACT

University of Maryland Extension conducted a needs assessment of Maryland urban farmers. Twenty-nine urban farmers completed a survey, which represents a large proportion of the urban farming population in this region. The majority of urban farmer respondents grew vegetables, fruits, and cut flowers in land-based production systems using raised-beds, in-ground growing, and high tunnels. Urban farmers prioritized balancing numerous goals, including producing food for themselves and their communities, creating jobs, and providing income for themselves. Financially, urban farmers were similar to the general farming population, with about half of respondents farming part-time and selling less than $10,000 of farm products. Extension educators with experience working with small-scale, diversified direct-market growers have knowledge and educational programs that can be relevant to urban farmers.

Introduction

Why this needs assessment?

Interest is high in urban agriculture, with many non-profits, businesses, municipalities, and individuals launching urban agriculture ventures. A Google News search of the terms “urban farming” and “urban agriculture” yielded 44,500 and 7,640,000 results, respectively.

Land grant institutions, including University of Maryland, University of the District of Columbia, Cornell University, Pennsylvania State University, and University of Nebraska, have appointed extension educators specifically to develop programming for the urban agriculture audience.

With so much excitement and interest in the topic of urban farming, it is important to base extension outreach on research-based information. This paper presents a needs assessment conducted in Maryland, to better inform urban agriculture Extension program development.

What is urban agriculture?

Urban agriculture has been most concisely defined by Wagstaff and Wortman (2013) as “all forms of agricultural production (food and non-food products) occurring within or around cities.”

Government agencies and the peer-reviewed literature have reached consensus on this broad definition of urban agriculture, which includes all production in or near cities of plants or animals, whether for personal use or for sale, whether soil-based or hydroponic (Diekmann et al., 2016; FAO, 2016; Hendrickson and Porth, 2012; Oberholtzer et al., 2014; USDA, 2016).

Agricultural production near cities is further defined as peri-urban agriculture (Diekmann et al., 2016; Hendrickson and Porth, 2012; Oberholtzer et al., 2014).

Literature review

Many previous studies have surveyed the existence and extent of urban agriculture (Smit et al., 2001; Heimlich and Barnard, 1992; Hendrickson and Porth, 2012; Rogus and Dimitri, 2015; Young et al., 2018; Taylor and Lovell, 2012) and the impacts of urban agriculture (Drakakis-Smith et al., 1995; Brown and Jameton 2016). There has been one published study of how Extension is currently addressing urban agriculture (Diekmann et al. 2016).

Two national-level studies have assessed the needs of urban growers (Oberholtzer et al., 2014; Kaufman and Bailkey, 2000). At the local level, needs assessments that surveyed urban agriculture communities include California (Reynolds, 2011; Surls et al., 2014), New York City (Cohen and Reynolds, 2014), Chicago (Taylor and Lovell, 2014), Kansas (Harms et al., 2013), and Wisconsin (Pfeiffer et al., 2014).

These studies have found that individuals and organizations engage in urban agriculture for many reasons: to improve their own health and economic situation, to improve food access in their communities, to create income and jobs, to beautify their communities, to educate about gardening and farming, to create a feeling of community, and to provide ecosystem services for their communities.

This study focuses on the goals and barriers to success of urban farmers, defined here as someone in an urban area who produces agricultural products for sale, in the Maryland area. Results are compared to both the 2014 national survey of urban farmers, and the 2012 census of the general farming population.

Methods

A research team at University of Maryland Extension (UME) conducted a needs assessment of urban farmers in the Maryland region.

Preliminary field work

From July 2016 through October 2017, we visited 31 urban farms and 3 peri-urban farms in and near Baltimore, MD. We used an emergent design flexibility approach (Patton, 2015), asking the farmers about their goals, perceived barriers, production methods, and experience with Extension. Based on these conversations, we developed a list of questions and hypothetical trends to test using formal needs assessment instruments and a purposeful sampling method.

Survey and formal interviews

To test the research questions, in 2018 we conducted an electronic survey and formal interviews. The survey was conducted electronically, using Qualtrics® software. The interviews were conducted either over the phone or in person. The University of Maryland, College Park Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the survey and interview methods, under project number 1013685-1.

The purpose of the survey was to gather quantitative and qualitative data from as many Maryland region urban farmers as possible. The purpose of the interviews were to gather qualitative data from a smaller number of key informants.

Because no complete list of urban farmers exists, survey and interview participation was solicited from two sample populations: (1) a list of 47 urban farmers identified during the preliminary field work and (2) the mailing list of 473 subscribers to Urban Ag E-News, published by UME. As an incentive, participants had the option to enter into a raffle for a $50 gift card to a seed company.

The first question on the survey asked respondents to identify themselves as either an urban farmer, a peri-urban farmer (near but not in a city), someone who wants to be an urban farmer, a gardener or homesteader, an entrepreneur, a government or non-profit employee (not primarily a farmer), or other. The survey used skip logic to display business-related subsequent questions (such as gross sales) only to those who self-identified as farmer or entrepreneurs.

Analysis

Because the population of urban farmers is small, Fishers’ Exact Test was used to compare this study’s responses to those of the USDA Census of Agriculture and the prior national survey of urban farmers (Oberholtzer et al., 2014). The software JMP® was used.

Results and Discussion

Sample size

A survey link was emailed to a list of 47 known urban farmers, 15 of whom responded to the survey. A separate email link, to an identical survey, was emailed to an urban agriculture e-newsletter mailing list of 473 public subscribers, 69 of whom responded. Of those 69 respondents, 12 self-identified as urban farmers and 2 as entrepreneurs. The results from the 15 respondents known to be urban farmers and the 14 respondents who self-identified as urban farmers or entrepreneurs, were combined resulting in a total sample size of 29.

This needs assessment was not a census, which makes definitive counts of urban farmers impossible. However, through more than two years of outreach to the Maryland urban farming community, 42 urban farmers in Maryland and 5 in the District of Columbia have been identified. Thus, although the sample size of the needs assessment survey is small, it represents a large percentage of the urban farming population.

Survey respondents were free to decide whether or not to respond to each question. The sample size for specific questions is listed in parentheses below. We also conducted four interviews. Results from those interviews are reported as quotes to contextualize the survey responses.

Who is the urban farming population?

Hypothesis: a higher proportion of urban farmers come from historically underserved communities than in the general farming population (n=27).

Compared to the 2012 USDA census of farmers in Maryland (USDA-NASS, 2012), a significantly higher proportion of respondents to this survey of urban farmers identified as female (Fishers’ Exact Test, P<0.05) or black (Fishers’ Exact test P<0.05) (Table 1). According to the census of agriculture, farmers in Maryland in 2012 were 81% male and 19% female, but urban farmers who responded to our survey were more equally split, with 52% identifying as male and 48% as female. In the 2012 Census of Agriculture, 98% of Maryland farmers identified as white, with no other category higher than 1%. In our survey of urban farmers, no one racial or ethnic group comprised a majority of respondents, with white (41%) and black (37%) being the two most common responses.

These results make it especially important that land-grant institutions and Extension programs work to serve urban farmers, because this population includes a high proportion of farmers from historically underserved communities.

Table 1. Responses to questions about sex and race/ethnicity from the 2012 Maryland USDA Census of Agriculture and this urban agriculture survey.

|

Demographic |

USDA Maryland Census of Ag (2012) |

This urban agriculture survey (n=27) |

Difference |

||

|

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

Count |

Percent |

|

|

Male |

81% |

9960 |

52% |

14 |

-29% |

|

Female |

19% |

2296 |

48% |

13 |

29% |

|

White |

98% |

18617 |

41% |

11 |

-57% |

|

Black |

1% |

220 |

37% |

10 |

36% |

|

>2 races |

NR |

NR |

15% |

4 |

|

|

Asian |

1% |

182 |

7% |

2 |

6% |

|

Hispanic /Latino |

1% |

211 |

0% |

0 |

-1% |

|

American Indian |

1% |

111 |

0% |

0 |

-1% |

|

Native Hawaiian |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

Hypothesis: Urban farmers bring non-traditional education and experience to farming (n=27).

Respondents were highly educated: 30% had some college, 37% had graduated college, and 26% had a graduate degree. Respondents reported a wide variety of major study in school, with the most common being the life/physical sciences, agricultural science, business, and the humanities. Similarly, respondents reported a wide variety of professional experience in addition to farming, with the most common being food service, landscaping/nursery production, teaching, business management or accounting, and sales. These results emphasize that urban farmers bring valuable knowledge and skills to their work, and that their foundation of knowledge may not include all the agricultural science and business concepts that traditional Extension programs might expect.

What production methods do urban farmers use?

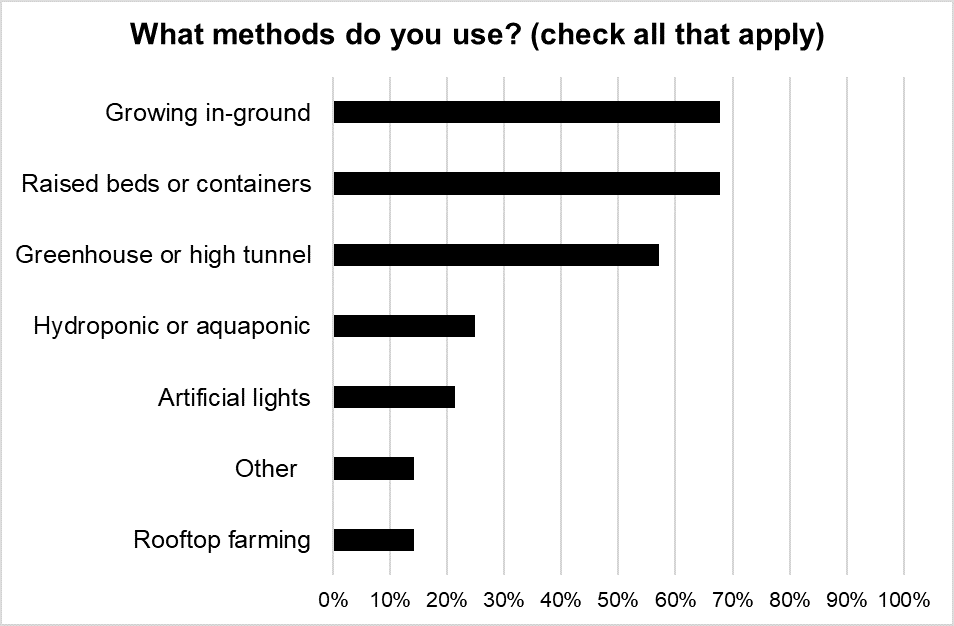

Hypothesis: most urban farms produce vegetables (n=28).

The majority of respondents produced vegetables, fruit, and cut flowers (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Most urban farmers who responded to this survey produce vegetables, fruit, and cut flowers. For this question, n= 28.

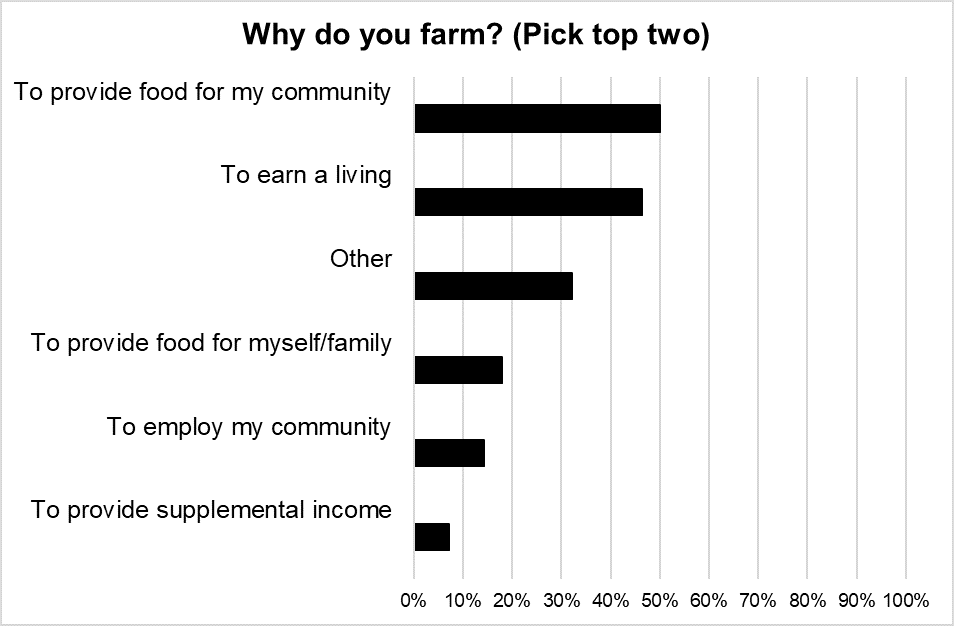

Hypothesis: Most urban farms are land-based, with a small percentage of high-tech hydroponic/aquaponics/vertical farms (n=28).

When asked to choose all that apply from a list of production methods, the majority of respondents reported growing in raised beds or containers (68%), in-ground (68%), and in greenhouses or high tunnels (57%) (Figure 2). A minority of respondents use hydroponics/aquaponics (25%), artificial or supplemental lights (21%), or rooftop farming (14%).

High-tech urban agriculture methods tend to get a lot of press, but the high proportion of urban farms growing in-ground and in raised beds means that Extension research and education for urban agriculture will need to be inclusive of low-tech production methods. Because the majority of urban farmers are ground-based and produce vegetables, fruits, and cut flowers, it may help Extension educators to think of urban farmers as a subset of small-scale, diversified, direct-market vegetable producers.

Figure 2. Most urban farmers who responded to this survey used ground-based growing methods such as growing in raised beds, in-ground, and in greenhouses or high tunnels (n=28).

Figure 3. Examples of land-based urban farming methods (raised bed, in-ground, and high-tunnel), at Whitelock Community Farm in Baltimore, MD. Photo by Neith Little, UMD Extension.

Figure 4. Examples of aquaponics production of leafy greens using both natural and supplemental artificial light at Envista Farms at Southern Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, in Temple Hills, MD. Photo by Neith Little, UMD Extension.

What are the goals of urban farmers?

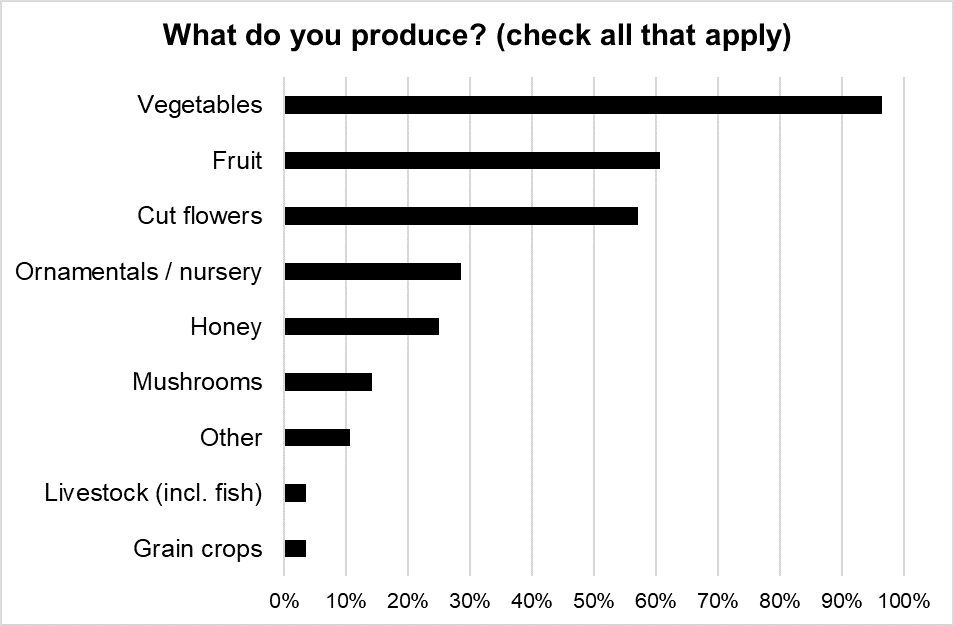

Hypothesis: Urban farmers strive to balance numerous goals, including producing food for themselves and their communities, creating jobs, and providing income for themselves (n =28).

Options for this question were formulated based on informal conversations with urban farmers. When forced to choose only two of these goals, the most popular choices were to provide food for their communities (50%) and to earn a living (46%).

However, “other” was a close third (32%). Of the respondents who chose “other” as one of their top two goals, 2 used the write-in option to list more three goals instead of two. Other write-in responses were different from the provided goal options, such as “to protect farmland from development,” “to beautify and build community,” and “to combat societal ills that plague our urban communities.”

These responses illustrate how dedicated many urban farmers are to community benefit through their work. Interestingly, three interview participants framed their primary goals as community building and food access and described financial sustainability as a means to achieving those goals, or lack of finances as a barrier to achieving their goals.

The economic realities of small-scale production can create a great deal of tension due to the dual goals of producing affordable food for the farmers’ communities and producing income for the farmers and farmworkers. While food access and food justice were important goals for many urban farmers, the additional goals of income generation, economic empowerment, and workforce development were also important because they are necessary for community development and community empowerment. The challenge of balancing these goals, and a case study of how one urban farm is working to overcome it, was described well in a recent Northeast SARE report by Lennon et al. (2018).

Figure 5. Urban farmers have many goals for their work, including both generating income and feeding their communities (n=28).

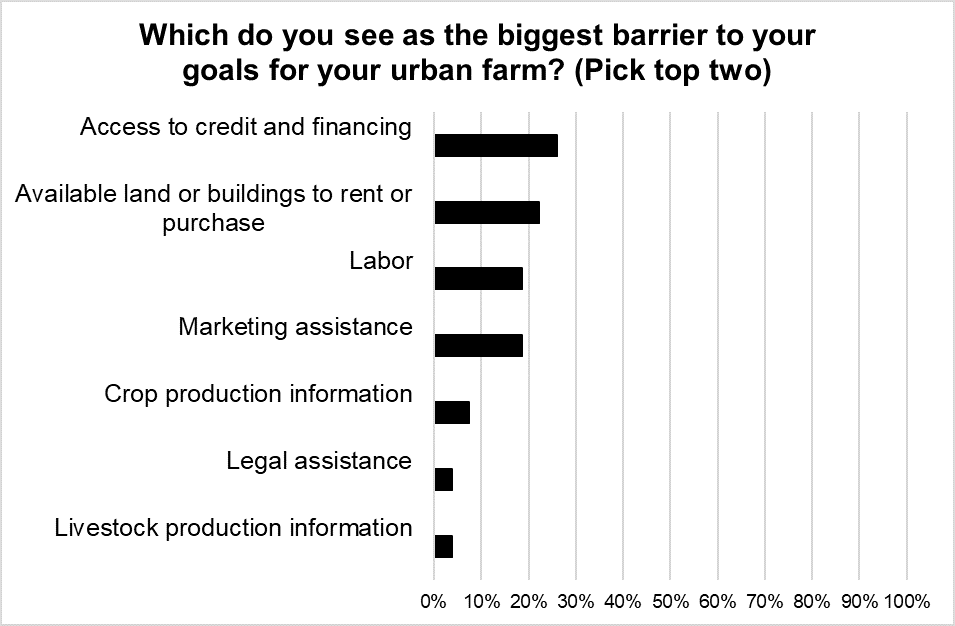

What do urban farmers see as the biggest barriers to achieving their goals?

This question was asked first as a qualitative, open-ended question, and then as a quantitative forced choice question (Figure 6, n=27).

Qualitative responses predicted many of the categories later displayed in the quantitative question. Other qualitative responses zeroed in on the tension between urban farmers’ goals described above, for example “finding a price point that is attainable for the community, while being able to provide a good quality of life for our employees.” Other barriers identified included water access and local policies and bureaucracy.

Figure 6. Access to financing and land availability were the most commonly identified barriers to urban farmers’ goals (n=27).

How does the income of Maryland urban farmers compare to other farmers?

Categories for gross sales were chosen to be comparable with the previous national survey of urban farmers conducted by Oberholtzer et al. (2014). Compared to Oberholtzer’s results, the survey of Maryland urban farmers found a similar distribution of income, with over 50% of respondents reporting gross sales of less than $10,000.

Table 2. Urban farmers’ gross sales were similar in this study, compared to a 2014 national survey of urban farmers. Among the farming population in general, the 2012 USDA Census of Agriculture also found that 57% of US farmers sold less than $10,000 gross.

|

Oberholzer et al. 2014 |

This survey of urban farmers |

||||

|

Category |

Percent |

Count |

Category |

Percent |

Count |

|

Less than $10,000 |

49% |

119 |

Less than $2,499 |

45% |

10 |

|

$2,500 to $9,999 |

9% |

2 |

|||

|

$10,000-$24,999 |

22% |

54 |

$10,000 to $24,999 |

5% |

1 |

|

$25,000-$49,999 |

10% |

25 |

$25,000 - $49,999 |

14% |

3 |

|

$50,000-$99,999 |

7% |

17 |

$50,000 to $99,999 |

5% |

1 |

|

$100,000-249,999 |

7% |

18 |

$100,000 to $999,999 |

18% |

4 |

|

$250,000-$499,999 |

2% |

5 |

|||

|

$500,000-$999,999 |

0% |

1 |

|||

|

$1 million or more |

2% |

4 |

$1 million or more |

5% |

1 |

Looking back to the goals that respondents identified for their urban farms, all of the respondents who did not identify an income related goal (make a living, supplemental income, employ people) as one of their top two goals also reported gross sales of less than $2,499. This underscores that for some urban farmers, income generation is a means to an end, rather than the goal itself. Additionally, these sales numbers are consistent with the general United States farming population. The 2012 Census of Agriculture found that 57% of the 2.1 million farms in the US sold less than $10,000 in agricultural products (USDA-NASS, 2014), similar to the 54% of the urban farmers in this survey and 49% of the urban farmers in Oberholzer’s 2014 study who sold less than $10,000 gross.

Urban farmers are also similar to the general farming population in their use of off-farm income. Forty-seven percent of urban farmer respondents to this survey reported farming part-time, while in the 2012 Census of Agriculture, 61% of US farmers reported working some days off the farm, and 52% reported having a primary occupation other than farming (USDA-NASS, 2014).

Conclusions

How can Extension better serve urban farmers?

Extension has a long history of serving the farming community (Rasmussen, 1989). The needs assessment result that a higher proportion of urban farmers come from historically underserved communities than is true of the general farming population emphasizes how important it is for Extension to similarly support the emerging community of urban farmers.

Extension educators can be heartened to know that they do have a lot to offer urban farmers. The majority of urban farmers in this study grow using methods that will be familiar to those who have worked with other small-scale, diversified, direct-market growers. It is important to increase the amount of research-based information on high-tech urban farming methods such as aquaponics, hydroponics, and rooftop farming. However a high proportion of urban farmers can be served by adapting existing programming on diversified vegetable production. In this survey, topics such as high-tunnel management, recordkeeping, specialty crop production, farm financial management, and sustainable pest management were highly prioritized by urban farmers, and many strong Extension programs on these topics already exist.

To customize existing Extension educational programs for urban farming audiences, it will be important to consider urban farmers’ goals, demographics, educational background, farming practices, and scale of production. For example, consider how financial education could be tailored to an urban farmer’s goals. Just as some rural farmers might see farm income as a means to preserve the legacy of a family farm, some urban farmers might think of improving their financial sustainability as a means to achieving the other goals they have for their farms of feeding, empowering, educating, and beautifying their communities. Framing financial sustainability in these terms could motivate participants to invest time in learning and applying what they learn. Additionally, what financial success looks like will differ depending on a farmer's goals. Farmers who prioritize affordable healthy food access might need to pursue different pricing and marketing strategies than farmers who choose to prioritize job creation and economic empowerment of community residents.

By adapting existing Extension programs in response to urban farmer goals and production methods, Extension can support urban farmers in both creating income for themselves and their employees and also benefitting their communities.

Literature Cited

Brown, K. H., and Jameton, A. L. (2016). Public health implications of urban agriculture. Journal of Public Health Policy, 21(1):20–39.

Cohen, N., and Reynolds, K. (2014). Resource needs for a socially just and sustainable urban agriculture system: Lessons from New York City. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 30(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170514000210

Diekmann, L., Dawson, J., Kowalski, J., Raison, B., Ostrom, M., Bennaton, R., and Fisk, C. (2016). Preliminary results: Survey of Extension’s role in urban agriculture. eXtension Community of Practice: Community, Local, and Regional Food Systems. Retrieved from https://foodsystems.extension.org/2019/03/survey-of-extensions-role-in-urban-agriculture-results/

Drakakis-Smith, D., Bowyer-Bower, T., and Tevera, D. (1995). Urban poverty and urban agriculture: An overview of the linkages in Harare. Habitat International19(2):183–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(94)00065-A

FAO. (2016). Urban Agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/urban-agriculture/en/

Harms, A. M. R., Presley, D. R., Hettiarachchi, G. M., and Thien, S. J. (2013). Assessing the educational needs of urban gardeners and farmers on the subject of soil contamination. Journal of Extension 51(1), 1FEA10.

Heimlich, R. E., and Barnard, C. H. (1992). Agricultural adaptation to urbanization: Farm types in northeast metropolitan areas. Northeastern Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 21(1):50–60.

Hendrickson, M. K., and Porth, M. (2012). Urban Agriculture — Best Practices and Possibilities. University of Missouri Extension Report. Retrieved from: http://extension.missouri.edu/foodsystems/documents/urbanagreport_072012.pdf

Kaufman, J., and Bailkey, M. (2000). Farming Inside Cities : Entrepreneurial Urban Agriculture in the United States. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper. Retrieved from http://www.urbantilth.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/farminginsidecities.pdf

Lennon, M., Regan, B., and Penniman, L. (2018). Sowing the seeds of food justice: A guide for farmers who want to supply low-income communities while maintaining financial sustainability. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education manual. Retrieved from https://projects.sare.org/information-product/sowing-the-seeds-of-justice-food-manual/

Oberholtzer, L., Dimitri, C., and Pressman, A. A. (2014). Urban agriculture in the United States: Characteristics, challenges, and technical assistance needs. Journal of Extension, 52(6), #6FEA1. Retrieved from http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84922015476&partnerID=tZOtx3y1

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Sage.

Pfeiffer, A., Silva, E., and Colquhoun, J. (2014). Innovation in urban agricultural practices: Responding to diverse production environments. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 30(1):79–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170513000537

Rasmussen, W. (1989). Taking the university to the people: Seventy-five years of cooperative Extension (First Edit). Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press.

Reynolds, K. (2011). Expanding technical assistance for urban agriculture: best practices for extension services in California and beyond. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 1(3):197-216.

Rogus, S., and Dimitri, C. (2015). Agriculture in urban and peri-urban areas in the United States: Highlights from the Census of Agriculture. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 30(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1742170514000040

Smit, J., Nasr, J., and Ratta, A. (2001). Urban agriculture: food, jobs, and sustainable cities. The Urban Agriculture Network. Retrieved from http://jacsmit.com/book.html

Surls, R., Feenstra, G., Golden, S., Galt, R., Hardesty, S., Napawan, C., and Wilen, C. (2014). Gearing up to support urban farming in California: Preliminary results of a needs assessment. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 30(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170514000052

Taylor, J. R., and Lovell, S. T. (2012). Mapping public and private spaces of urban agriculture in Chicago through the analysis of high-resolution aerial images in Google Earth. Landscape and Urban Planning 108(1):57–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.08.001

Taylor, J. R., & Lovell, S. T. (2014). Urban home gardens in the Global North: A mixed methods study of ethnic and migrant home gardens in Chicago, IL. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 30(01):22–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170514000180

USDA-NASS. (2012). Census of Agriculture State Data: Maryland Selected Operator Characteristics.

USDA-NASS. (2014). 2012 Census of Agriculture highlights: Farm demographics, (800), 1–4. Retrieved from https://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2012/Online_Resources/Highlights/Farm_Demographics/Highlights_Farm_Demographics.pdf

USDA. (2016). Urban Agriculture Tool Kit. United States Department of Agriculture Publication. Retrieved fromhttps://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/urban-agriculture-toolkit.pdf

Wagstaff, R. K., and Wortman, S. E. (2013). Crop physiological response across the Chicago metropolitan region: Developing recommendations for urban and peri-urban farmers in the North Central US. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 30(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S174217051300046X

Young, L. J., Hyman, M., and Rater, B. (2018). Exploring a Big Data Approach to Building a List Frame for Urban Agriculture: A Pilot Study in the City of Baltimore: Journal of Official Statistics 34(2):323-340. Retrieved from: https://content.sciendo.com/view/journals/jos/34/2/article-p323.xml

Acknowledgements

The IRB protocol does not allow for thanking study participants by name, but we wish to express our profound gratitude to the farmers and growers who let us visit their farms, took the survey, were interviewed, and took the time to share their knowledge and experience. We hope that the results of this study will help Extension educators better support your endeavors. The Farm Alliance of Baltimore was particularly helpful in connecting us with urban farmers. We also wish to thank Dr. Darren Jarboe for review of an early draft of this paper, and the editor and reviewers of the Journal of the National Association of County Agricultural Agents, for their constructive review comments.